Brief Encounter review

Famous love affair feels trapped by period stylings in an otherwise charming production

Since it was first seen in 2008, Emma Rice’s take on this classic romance – smooshing together the 1945 David Lean film and Noël Coward’s earlier one-act play, as well as various of his songs – has become the definitive stage version. Now, Sarah Frankcom returns to the Royal Exchange to direct it.

It’s obvious why: using Coward’s own numbers to allow these ordinary, distinctly repressed characters to let their innermost feelings explode via song really works. Throughout, lovely live music helps inflate their emotions, with almost scene-stealing energy from pianist and musical director Matthew Malone.

And yes, we are talking about characters, multiple: the station staff’s love lives are given almost as much time as the central doomed affair. But this shifts the tone of a story most will know from the film as a classic study in yearning; here, it becomes much more of a larky comedy, thanks to the sweet or saucy interactions of its other lovers.

At times, I felt the contrast between the working-class cheeky humour and the middle-class, ter’bly, ter’bly earnest emotion falls back on old archetypes, rather than interrogating them. But the cast in the supporting roles shine: Christina Modestou is amusingly stern yet lusty as the tearoom manager, while the youthful, trembly attraction between the waitress (Ida Regan) and her adoring beau (Georgia Frost) is full of charm. Regan really proves one to watch, switching effortlessly between endearingly dorky when serving tea, and sumptuously grand when delivering a velvety, internal rendition of Mad About the Boy.

Continues...

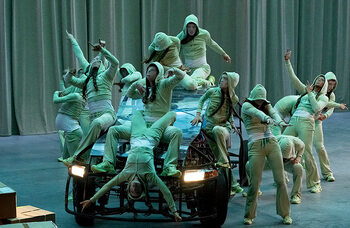

Grand, too, is Rose Revitt’s train station set – a splendid parquet floor feels both appropriate for the station cafe, and spins smartly to evoke a railway turntable. And mention must go to Russell Ditchfield’s outstanding sound design: there are moments when it feels like a train is rattling the very metal skeleton of the theatre.

If it seems as if I’m circling around the central duo, the respectable Laura and Alec, it is probably because I never quite believed in them. Hannah Azuonye and Baker Mukasa feel trapped, somehow, in a cage of their clipped 1940s British accents; little of what they say – or their aching subtext – convinces emotionally. Some loving expressions even prompted stifled titters among the audience, because their bright, prissy delivery sounds almost parodic. Frankcom’s staging of some of their talkier scenes, which sees them drifting between café tables, feels oddly listless.

Making the rest of the show more of a laugh doesn’t help us take Laura and Alec seriously, and of course it’s always a tough task living up to the memory of Celia Johnson and Trevor Howard in the movie. But without a strong sense of the depth of their attraction, this encounter is not only brief, but also shallow.

More Reviews

More Reviews

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99