We’re all mad here, or so Joe Penhall would have us believe. His play, which premiered at the National Theatre in 2000, constructs a spry pas de trois between a white psychiatrist, a white consultant and their black patient. As they diagnose and bicker Penhall makes it increasingly clear that doctors are no better at keeping hold of their marbles than the rest of us.

The timeliness of this revival is obvious. Robert the consultant wants to get patients out of the hospital quickly because there aren’t enough beds. Junior doctor Bruce still has the youthful idealism of trying to do the best for his patients. All the while, the patient Christopher is piggy in the middle. Robert also sees Christopher’s race as being medically relevant, if only because a juicy case study like this can help him finish his book and climb the greasy pole to promotion.

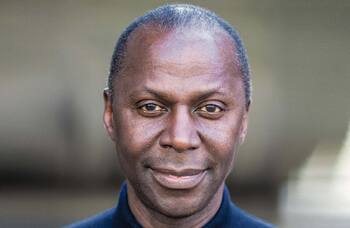

Daniel Kaluuya as Christopher is restive and jittery. He makes faces and adopts funny voices. He’ll shout suddenly, and then laugh in the same instant. We see him in flashes, impossible to pin down. Vocal tics – ‘do you know what I mean’ – are embedded between lines with such speed and consistency that it’s as though he’s been saying them all his life.

Luke Norris’s persistent and slightly shrill voice, increasingly exasperated and almost desperate as young doctor Bruce, meets David Haig’s astonishing comic ability. Every single word from Haig as consultant Robert is stretched or spat for fullest effect – for humour, for drama or, most of the time, for both.

Throughout the play it’s impossible to decide who or what is right or wrong, whether this is funny or tragic. Director Matthew Xia brings out the best in the three performers. Authorities and dominance bounce back and forth like ping pong balls as ethics meets expedience; one man’s diagnosis is another man’s crackpot theory.

The doctors lock horns on blue textured lino and blue, uncomfortable institutional chairs, while underneath the square consulting room is a waiting room barely visible through submerged windows. We walk through it to get to our seats and see the extraordinary attention to detail for all of a few seconds: health and safety posters on the walls and, brilliantly, a lingering smell of citrus.

As Kafkaesque as the situation becomes, as comic as Haig makes his performance, it’s always the right side of believable. Penhall inverts and imbalances the relationship between doctor and patient. The mad are sane, the sane are mad. Blue is orange. Or not. Sixteen years on and the satire is still sharp. But this is less a bitter pill and more suppository as Penhall tells cocksure and arrogant men, and the politicians who meddle with healthcare, to shove it up their proverbial posteriors.

More Reviews

More about this organisation

More Reviews

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99