Michael Coveney: Has the wheel come full circle for amateur theatre in Britain?

Amdram has a colourful history on the British stage, from ‘little theatres’ in the early 1900s to today’s programmes at the National and RSC. Michael Coveney takes a look at how it has developed over time

Amateur, in some circles, is an everyday pejorative term. Prominent in every critic’s lexicon is the insult “amateurish” whenever the set falls over, the doorknob comes off, actors fluff cues and the third-act inspector enters with paper snow on his head.

All this, and a whole lot more, happens in The Play That Goes Wrong, and it’s a sure sign of how much we relish the mishaps and miscues of theatre in all its manifestations that the irrepressible Mischief Theatre’s glorious debacle has been such a hit on both sides of the Atlantic, and a template for their subsequent work.

Terence Rattigan’s Harlequinade in 1948 and, especially, Michael Frayn’s 1982 work Noises Off, not to mention Alan Ayckbourn’s A Chorus of Disapproval two years later, feed off the “goes wrong” mythology. Rattigan and Frayn do so in a lowly provincial rep, while Ayckbourn anatomises an amateur light opera society beggaring belief in The Beggar’s Opera.

For the stage premiere at the Stephen Joseph Theatre in Scarborough, of what he’d hoped would be a play about amateurs putting on The Vagabond King, Ayckbourn had wanted to have dozens of amateurs dotted around the audience standing up with a song-linking commentary on the Rudolf Friml operetta.

But the Friml estate refused the rights and the Scarborough Operatic Society, who had been approached to take part, wanted their members to take only leading roles. Equity ruled that to include amateurs in this way was unacceptable (that stricture probably would not apply today). So the ever-pragmatic playwright turned his attention to an amateur company played by professionals putting on John Gay’s folk opera.

Rattigan’s play was premiered not long after the establishment of the Arts Council. Until then, there was no real sense of an amateur/professional divide in the British theatre. The British Drama League had been formed in 1919 to launch a campaign of reinvigoration. ‘Little’ theatres – amateur groups and societies – sprouted like billy-o during the next two decades from Norwich to Halifax, alongside the repertory theatres in Hull, Leeds and Liverpool, and the club theatres in London.

This was the heartbeat, and the future, of British theatre. Critics and commentators reported on the activity in both parallel, complementary spheres.

‘Little’ theatres were the heartbeat, and the future, of British theatre

St John Ervine of the Observer, himself a dramatist, was a prominent advocate of the amateur Little Theatre movement, where the programme was similar to that of the new reps and club theatres: the plays of Bernard Shaw – who was virtually a patron saint of the amateurs, offering them encouragement and reduced royalty arrangements – as well as the European repertoire of Brecht, Karel Capek, Pirandello, André Obey and Chekhov.

In London, in the early 1930s, the Tower in Islington and the Questors in Ealing – both still going strong today – set a benchmark in standards and repertoire that prefigured the National Theatre and the Royal Shakespeare Company.

After Pinter’s The Birthday Party flopped in 1958, the first London revival, one year later, was at the Tower. The future Royal Shakespeare Company associate director David Jones, then working at the BBC, played McCann. Pinter said of this production that it was the best there had been “and, I am sure, the best there will be”.

The organised political theatre of the 1930s was almost exclusively amateur, starting with such sterling projects as the People’s Theatre in Newcastle (nursery of actor Kevin Whately and comedian Ross Noble) founded in 1911 by the captain of Newcastle United Football Club, Colin Veitch, and an avowed branch of the British Socialist Party.

And at the still thriving Maddermarket in the heart of medieval Norwich, the director Nugent Monck created in 1922 Britain’s first Elizabethan-style thrust stage – it was, and still is, unbelievably tiny. By 1937, Monck had staged the complete Shakespeare canon in a fast, uncluttered style that influenced Tyrone Guthrie, Barry Jackson (who had founded Britain’s first purpose-built rep, the Birmingham Rep in 1911) and his protégé Peter Brook.

The amateurs were highly active in Birmingham in the 1920s, not least in the Council House, Victoria Square, where the Municipal Players, all employees of the Corporation of Birmingham, put on shows in the canteen, formed study groups, a playwriting competition and a summer school of acting under the direction of WG Fay, co-founder with WB Yeats and Lady Gregory of the Abbey Theatre in Dublin.

In 1930, Sybil Thorndike made a speech in the city declaring that the theatre in Britain was passing through a “queer time” and needed to pull its socks up, but that “the biggest sign of revival” lay in the steady growth of amateur societies all over the country. The Municipal Players morphed into today’s still legendary Crescent Theatre in 1932.

The wheel has come full circle. The RSC has amateurs at the core of its activity – the pro-am A Midsummer Night’s Dream in 2016, with amateurs playing the mechanicals, is the tip of a large iceberg.

The wheel has come full circle – the RSC’s pro-am A Midsummer Night’s Dream in 2016 is the tip of a large iceberg

The policy seems to be to create a much-needed new audience through involving not only schools, but entire local communities. Whether this will pay box-office dividends remains to be seen. And is the effort diluting the prestige and status of what is still, though more mutedly, described as one of the world’s leading companies?

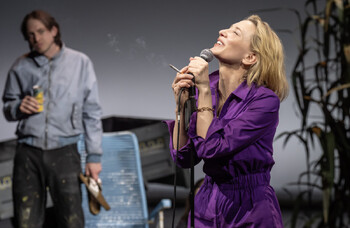

There’s a hint of this at the National, too, with the adoption of the Public Acts programme in New York. Its first fruit was a rumbustious Pericles with about 200 amateurs on the Olivier stage two years ago.

Amateurs have played their part at the NT since 1991 when the BT Biennial produced plays by John Godber, Debbie Isitt and Peter Whelan in conjunction with the Little Theatre Guild, the nationwide organisation representing amateur companies that own their own venues. This was succeeded by the indisputably terrific NT Connections, which involves schools nationwide in plays by professional dramatists.

In the past two years, I’ve travelled from the Theatre Royal in Dumfries and Galloway, the oldest operating theatre in Scotland, theatre of Robert Burns and JM Barrie and saved by amateurs in 1959, to the Minack in Cornwall, carved from a cliff overlooking Porthcurno beach by the extraordinary Rowena Cade and her gardener in 1932.

And I’ve fulfilled at last a long-festering desire to write about the amateur theatre in Ilford, Essex, where I grew up. The Renegades was run by another extraordinary character, James Cooper, who elicited my first reviews at the Monday meetings (or post-mortems) following each monthly production. I was well placed to do this having not been cast in that monthly production on a regular basis.

I once asked Toby Jones had he ever done any amateur acting. “Why, does it look as though I have?” he replied. In my case, I would have looked like an amateur even in the amateur theatre. I soon found more appropriate ways of finding my kicks and receiving them.

Questors, Jesters and Renegades: The Story of Britain’s Amateur Theatre by Michael Coveney is published by Methuen Drama on March 5. Details: bloomsbury.com

The unlikely pair who built the Minack Theatre return to its stage

Opinion

Recommended for you

More about this organisation

Advice

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99

Michael Coveney

Michael Coveney