Mark Shenton’s week: The joy and sadness of getting up close and personal with stars

It’s always a treat to see stars who are used to appearing in large arenas or theatres bring their shows down to a more human scale again, and the weekend before last I saw two on the same night in New York.

Derren Brown, who these days plays some of the largest theatres in the land in Britain, is current making his New York debut with a show called Secret at Off-Broadway’s 199-seater Atlantic Theater, running to June 25. I’ve been so enthralled and utterly baffled by it that I’ve seen it twice there – I saw its second preview back in April, and have now gone back.

Part of the secret of Secret is, as ever, a plea for audiences to keep it that, so as not to spoil the enjoyment of future audiences, and I have no intention to break that necessary embargo. But I couldn’t reveal how he does it, because even after seeing it twice I have no absolutely no idea.

Suffice it to say that on the first occasion I found myself an integral part of the onstage action – never a comfortable place for me to be, to be honest – when I was asked to draw something. Since I patently can’t draw (let alone hand-write anymore), it was almost embarrassing. However, I went with the flow, as you have to, and loved it.

Only an hour after seeing him again last Saturday I was uptown at 54 Below, an intimate Broadway cabaret club, to see Tim Minchin perform an informal, deliberately scrappy late-night cabaret. Given that these days he gigs at places such as the Royal Albert Hall, it felt like a really special thing to see Minchin performing to such a small crowd again – and it was clearly as much a pleasure for him as it was for us.

That’s the sign of an authentic performer: someone doing it simply for the shared love of it.

Pacific Overtures downscaled but upping the ante

There are few Broadway musicals I wish I’d seen in their original productions more than Pacific Overtures, Sondheim’s blazingly audacious 1976 show about Imperial-era Japan and what happened when the West first started calling in 1853, with America parking its warships off its shores.

That original production ran for only six months but, staged by Hal Prince in Kabuki-style, with men playing women’s parts, it still sounds startling. Over the years since, I’ve seen a number of productions of the show (including its UK premiere at Manchester Library Theatre’s Wythenshawe Forum in 1986, and again at Leicester Haymarket in 1990, a production at English National Opera in 1987, another at the Donmar Warehouse in 2003 as well as a stunning fringe revival at the Union in 2014). but last weekend I saw the best I’ve seen yet.

It is directed and designed by John Doyle, the British theatre director who is now Manhattan-based as artistic director of Off-Broadway’s Classic Stage Company. Doyle has regularly staged Sondheim shows, including the transfer of his Watermill production of Sweeney Todd to Broadway, an actor-muso production of Company from Cincinnati to Broadway, and productions of Road Show (at the Public in New York and Menier) and Passion (at CSC before he took over).

Sadly, the run ended yesterday (June 18), so you’ve missed it; but staged with a thrilling intimacy on a traverse stage by a small (12-strong) ensemble cast, this reduced version of the show that runs to just 90 spellbinding minutes lays out its themes with real clarity and dramatic momentum. I hope Doyle brings it to London; perhaps the Menier could be a good home for it?

Whitney Houston – a life destroyed by demons and fame

Last week, I saw a screening of Nick Broomfield’s haunting new documentary Can I Be Me, about the life, career and death of Whitney Houston, piecing together backstage footage of concerts and interactions with family, husband and daughter.

It’s a piercing story of addiction, celebrity and the price of fame, and also touches on issues around her co-dependent relationship with her husband Bobby Brown and assistant Robyn Crawford. Even Brown has admitted after her death: “I really feel that if Robyn was accepted into Whitney’s life, Whitney would still be alive today. She didn’t have close friends with her anymore.”

This film is a cautionary tale and a brilliant real-life insight into a woman whose life has so far only been celebrated theatrically by a stage version of her most famous screen role in The Bodyguard that recycled some of her greatest hits. I’ve long enjoyed that show as a guilty pleasure, seeing it several times in its original West End run at the Adelphi and its return to the Dominion, as well as its US premiere at New Jersey’s Paper Mill Playhouse last year.

There’s a lot of guilt, but not a lot of pleasure, around how Houston found herself and her immense talent being destroyed by those who failed to protect her, professionally and personally, from the toxic relationships around her – and not letting her be true to herself.

Opinion

Recommended for you

Advice

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99

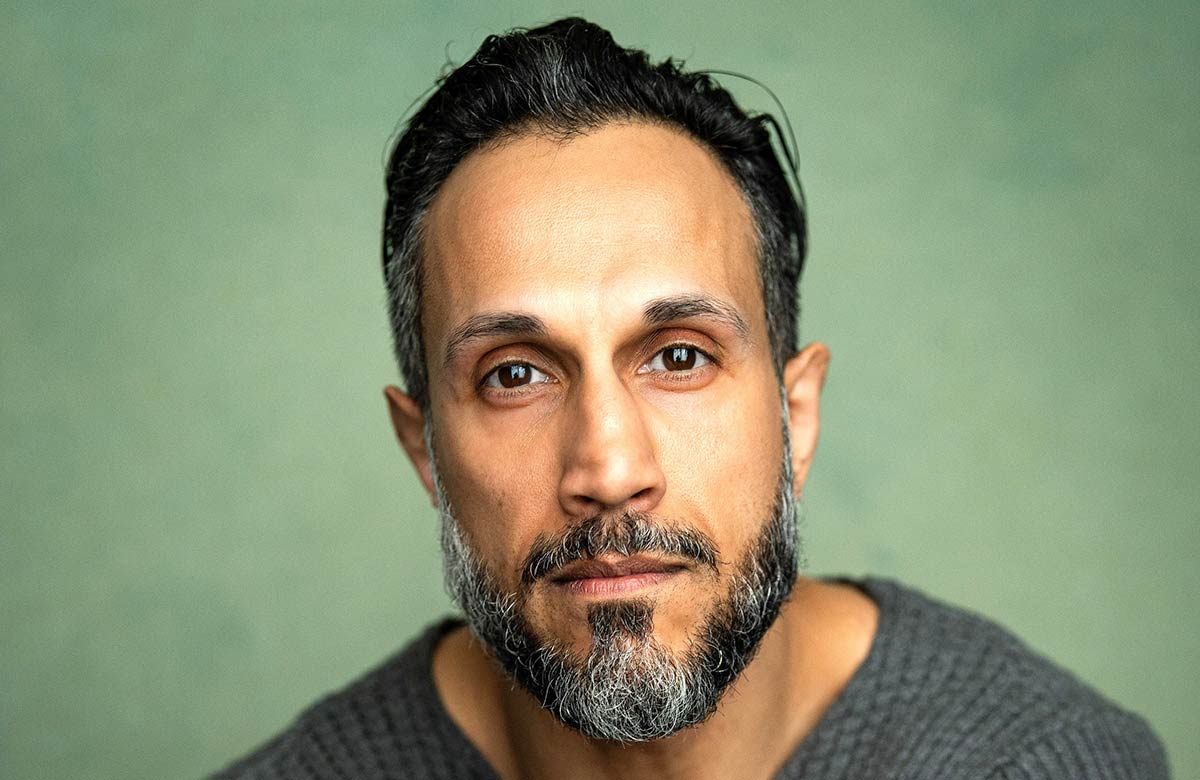

Mark Shenton

Mark Shenton