What we can learn from 40 years of New York theatre history

It was entirely unintentional that I scheduled myself to see two shows in Manhattan Theatre Club’s adjacent Off-Broadway theatres on successive days last week. So it was only as I travelled down the slightly vertiginous stairs to the basement spaces at New York City Center on Saturday that it dawned on me that it was exactly 40 years ago this month that I began a season of running up and down those same stairs. That was the year I worked as a press assistant at MTC, and it coincided with the still young company’s transition from New York’s Upper East Side to just slightly north of the theatre district.

My hike up and down those flights twice in two days (though there is an elevator) provoked less of a personal reflection, or even a professional one, than a mental survey of how New York theatre has changed over that time. A four-decade viewpoint throws into relief how much has been done in recent years – especially regarding equity vis-à-vis gender, race, ethnicity and disability, as well as efforts to fight against pay inequality, sexual harassment and more – against a backdrop of a national health crisis that has substantially altered long-standing audience patterns.

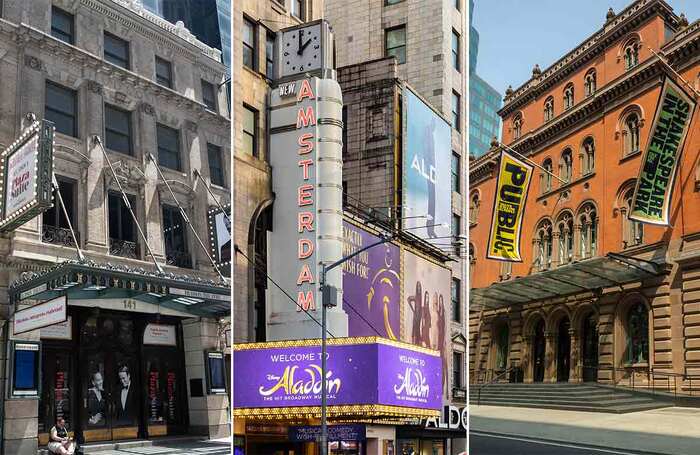

In thinking about the New York theatre that I have experienced, change has been, well, a constant. While Broadway had lost several theatres shortly before I turned up in NYC in 1984, remarkably, new ones have since opened and dormant ones have been restored. The list of openings and reopenings includes the Marquis in 1986, the New Amsterdam in 1997, the Lyric (initially the Ford Center, which combined two dormant houses) in 1998, the Todd Haimes (originally the American Airlines) in 2000, the Sondheim in 2010 and the Hudson Theatre in 2017.

Those new and revived venues stand in contrast to the Broadway of the mid-1980s, which saw the Nederlander Organisation first lease, then sell, the Mark Hellinger Theatre to the Times Square Church. While from then until now, the number of new productions on Broadway (excluding concerts) has remained more or less constant, the late 1980s and early 1990s were seen as a period of decline, perhaps most notably in 1994-95 when only two new musicals opened all season, and only one – Sunset Boulevard – had an original score. That era of dismay over Broadway’s fate was progressively dispelled as the decades passed and sales – and prices – grew with demand: the 1984-85 season had a total gross of $209 million, and in the last full season pre-pandemic lockdowns, Broadway hit $1.8 billion.

Continues…

Beyond Broadway, there was even more change. Companies that were influential at varying scales faded out. The Ridiculous Theatrical Company ultimately closed following the loss of its guiding light Charles Ludlam to AIDS. Circle Repertory Company, home to a squad of distinctly American playwrights, most prominently Lanford Wilson, was all but gone by the late 1990s. WPA Theater, which fostered the creative team of Howard Ashman and Alan Menken and birthed their perennial hit Little Shop of Horrors, ceased production come the new millennium. The estimable Negro Ensemble Company, following important work particularly in the 1960s and 1970s, would cease under its original structure by 1990.

Yet many other companies began or significantly grew in this period, now familiar names like the Atlantic Theater Company, Theatre for a New Audience, Signature Theatre Company, Second Stage Theater, Primary Stages and MCC Theater among them. The steady blurring of lines between not-for-profit and commercial was accelerated as Roundabout Theatre, Second Stage and Manhattan Theatre Club all established Broadway homes. The theatres have been instrumental in keeping plays present on Broadway, although even they now dip into the more lucrative world of musicals too.

There are a few genuine constants Off-Broadway. Most notably the Public Theater’s home on Astor Place, which has remained its base even as other theatres expanded. There’s also the unrivalled tenure of Lynne Meadow as artistic director of MTC, dating back to the early 1970s, rolls on. And don’t forget the tendency of the media – legacy and new – to pay more attention to Broadway, when work in smaller spaces is at least as compelling and often more influential to the field’s pursuit of art, not just commerce.

Continues…

This precis of New York theatre history is hardly complete. It’s simply a gloss of what came to my mind last Saturday, when I saw Vladimir by Erika Sheffer – the story of journalists in the early years of Putin’s takeover of Russia – and again on Sunday when I saw Fatherland, a verbatim play devised and directed by Stephen Sachs, drawn from court transcripts of a man on trial for his role in the January 6 US Capitol riots. Both were politically minded works that could be seen as existing in coincidental conversation with one another, since Vladmir was produced by MTC while Fatherland, a transfer from the Fountain Theatre in Los Angeles, was a rental by MTC to a small commercial production.

This capsule of mine also focuses on companies, and buildings, not art, because it is a macro view, and because there has been dynamic creativity throughout. There’s no question that there’s a wider range of work on offer now, and that the white men who dominated decades ago as playwrights, directors and artistic directors have of late had to literally share many of these stages; surveys such as the Count by the Lillys and the Dramatists Guild and the Visibility Report by the Asian American Performers Action Coalition have been essential in both prompting and recording those shifts.

Yes, I can miss certain aspects of the New York theatre that existed at the beginning of my career – the Promenade Theatre on the Upper West Side, half-price Broadway tickets at TKTS that cost perhaps $25, standing in the lobby of the New York Times waiting for the first papers to come off the printing press so I could ferry the reviews back to my bosses – but while I believe the history is important to understanding how we got to where we are, it’s more important to focus on where we are today and how we get somewhere better. After all, theatre can change. I’ve seen it happen.

This week in US theatre

John Leguizamo and Luna Lauren Velez lead the cast of The Other Americans, which begins performances tonight (October 18) at Arena Stage in Washington DC. Ruben Santiago-Hudson directs Leguizamo’s new play, which, in contrast to his earlier stage comedies, is described as a drama about a laundromat owner struggling with a failing business.

Jamie Lloyd’s radical look at Sunset Boulevard, with its book and lyrics by Don Black and Christopher Hampton and score by Andrew Lloyd Webber, opens on October 20 on Broadway. Nicole Scherzinger repeats her lauded London performance as Norma Desmond.

Delia Ephron has turned her memoir of late in life romance, Left on Tenth, into a Broadway play, opening on October 23 with Julianna Margulies and Peter Gallagher in the central roles, directed by Susan Stroman. It continues a Broadway legacy for the Ephron family, following plays by her sister Nora (Lucky Guy; Imaginary Friends) and parents Phoebe and Henry (Take Her, She’s Mine; My Daughter, Your Son).

Ngozi Anyanwu invokes the myth of musician Robert Johnson and two souls meeting at a Mississippi crossroads in Leroy and Lucy, beginning performances at Steppenwolf in Chicago on October 24. Awoye Timpo directs Jon Michael Hill and Brittany Bradford in the title roles.

Kit Connor and Rachel Zegler are the latest in a long line of Broadway’s tragic teen lovers, with Romeo + Juliet opening on October 24 under Sam Gold’s direction, in a production that prominently features music by Jack Antonoff and choreography by Sonya Tayeh in its marketing.

Opinion

Recommended for you

Advice

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99

Howard Sherman

Howard Sherman