Developing Relationships

Just as the Olympics celebrations were dying down last year, a completely different set of fireworks was lighting up the theatre world. While a horrified industry watched Newcastle City Council propose a 100% cut to its arts budget – the council has since stepped back from this idea, but will still reduce its support to around 50% – Nicholas Hytner passionately lambasted the government’s attitude towards funding.

“Culture secretary Maria Miller says she expects philanthropy to double in the coming year. She hasn’t said how,” he railed. “We have raised £14 million over the last couple of years towards our redevelopment, but that is because we are properly funded in the first place. Private money follows public money.”

Miller came out fighting, but it was a cold wash of reality at the end of a stellar year for the arts.

[pullquote name=”John Rodgers”]We work very closely with the National Theatre’s creative team because we couldn’t do our job effectively if we didn’t[/pullquote]

With the economy contracting, development departments have never been more important. But even to this day, it appears some in the industry are ambivalent about this role and see fundraising as nothing more than a necessary evil. Such tension is understandable – no one likes to talk, think, or be asked to do something because of money – but when carried out properly, development is the lifeblood of an institution. For many theatres – even some of the biggest – this is not hyperbole.

“The development department plays an absolutely central part because we have no regular subsidy,” explains Vivien Wallace, development director of the Old Vic. “When Kevin [Spacey] first came here, everybody said, ‘Oh, it can’t be done without subsidy’, because Peter Hall and Jonathan Miller couldn’t do it. The fact that we’re here nine years later is rather astonishing.”

Wallace confirms they have been lucky to have Spacey’s star power, but says it is more important that he is an artistic director who understands the importance of fundraising. “Kevin has a very clear sense of what the Old Vic is, [and] he has that American ability to ask, which the English find very difficult. He can make the case and say, ‘I need your help, and will you do X?’.”

She posits that although tax breaks are supposedly the biggest incentive to philanthropy, the real issue on this side of the Atlantic is a cultural one.

“Americans don’t want big government intervention. They want to say they’re individuals, and they want to say where their money goes.” The British sense of such individual giving, she says, is buried with the Victorians and harder to excavate. For all Spacey’s importance, Wallace is adamant that development can’t work unless “everyone mucks in”.

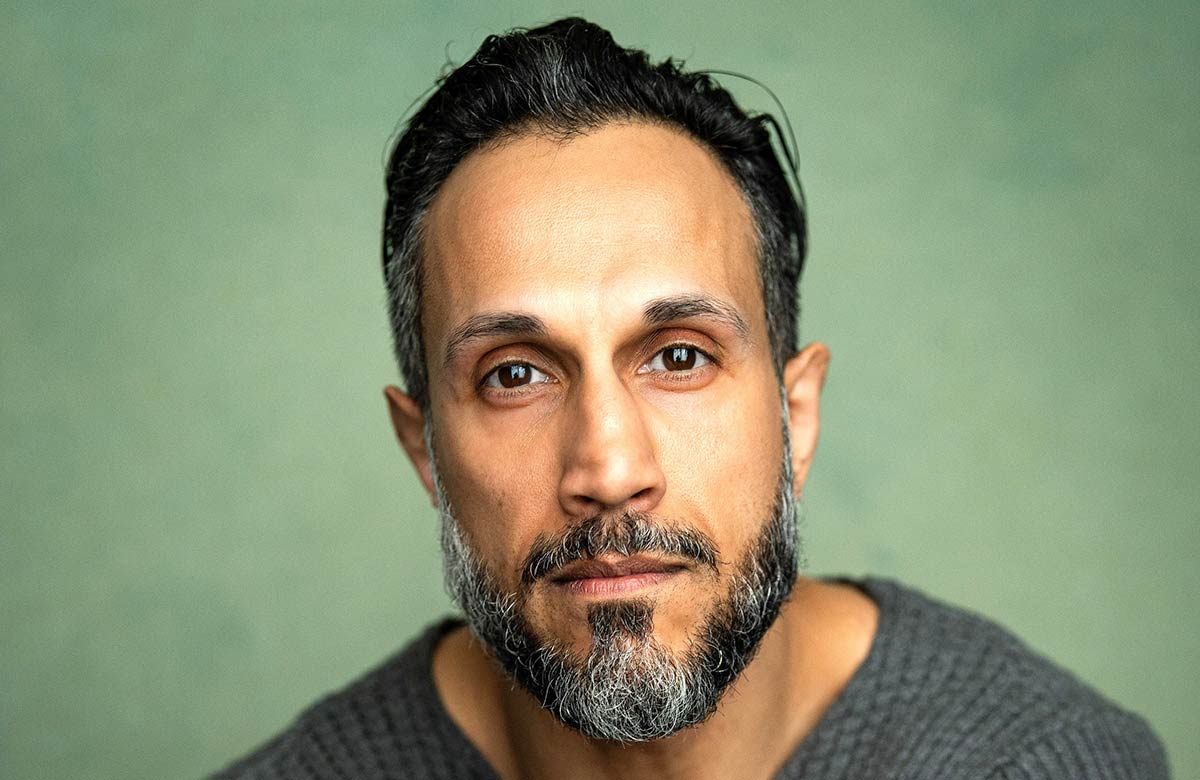

Equally, John Rodgers, director of development at the National Theatre, believes collaboration at both management level and beyond is crucial, and that a continually fluid relationship with the artistic team is essential to successful fundraising. “We work very closely with [the creative team] because we couldn’t do our job effectively if we didn’t,” he says. “We want to learn what they are planning and involve them in helping to communicate those plans to our supporters.”

Over at the Bush Theatre, the development department reads incoming scripts and is involved in weekly meetings with the artistic team, contributing to programming and commissioning discussions. Development director Melanie Aram believes it is vital for her department to be completely integrated in the Bush’s artistic process. “Much of what the department does is to articulate a narrative for the Bush and to facilitate relationships that will support progress,” she says.

Battersea Arts Centre’s development manager Fezzan Ahmed agrees. “Relationships are the main thing,” he says. “The closer we work with the creative team, the truer the fundraising story is, which means the better the relationship is with funders.”

Of course, the proof of such integration is in the pudding. Wallace, who prior to her position at the Old Vic began theatrical fundraising at the NT at a time when its department was marginalised and looked down on by the creative team, says: “Obviously it is different now, of course. When you’re doing so well, it has to be.” Rodgers’ no-nonsense assertion of his department’s closeness to the creatives at the NT bears this out.

A strong artistic understanding enables development teams to link the right donor to the right project. Rodgers speaks of “tailor-made proposals”, while Bristol Old Vic’s development head Alan Wright’s advice to anyone wanting to build such a department is: “Categorise your needs. Then think how best to address them. Transform those critical needs into attractive propositions.”

This may sound like City jargon, but the ability to straddle two worlds is vital to their success. Even so, it is also necessary to have a wealth of contacts from within the world of the sponsors, claims Aram. “Peer to peer fundraising is considered one of the most successful modes [of] making the most of your trustees’ contacts and abilities,” she says.

Wallace agrees, pointing out that the London Old Vic’s newly instigated development committee has proved strategically invaluable.

Perhaps the most important role of development, however, is in making sponsors feel that they are part of the team.

“It is vital that everyone supporting Bristol Old Vic has a sense of ownership,” says Wright. “We want to demonstrate that every penny of support has been well spent. As we build our reputation, all our supporters are able to bask in the reflected glory of our success.”

Or, as Wallace puts it: “To show that it’s a win-win situation.”

As ambassadors for the arts, these fundraisers are as passionate about the work as they are about finding the money for it. “The department’s role is transformative – to make the aims and ambitions of the theatre move from idea to reality through carefully targeted financial investment,” says Aram. Rodgers concurs: “The department raises funds to be able to afford our full ambitions.”

With dire economic circumstances putting such hopes and dreams in danger of being quashed, the need for such individuals has arguably never been greater.

Opinion

More about this organisation

Advice

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99