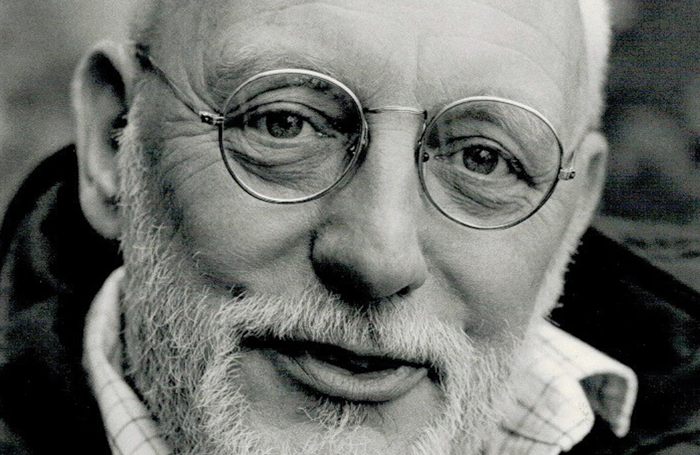

Obituary: Charles Wood – multiaward-winning writer for stage, TV and film

Charles Wood’s career blossomed in the 1960s as anti-war subjects were becoming popular, but his work was complicated by unshakeable affection for army life formed by his five years in the 17th/21st Lancers regiment.

His first piece, Prisoner and Escort (1959), was a one-act play sold to radio, then theatre, then television. His first full-length work, Dingo, set in Second World War Africa, was bought by the National Theatre in 1961 but banned by the Lord Chamberlain until 1967. Wood described it as a “camp concert”, but it was also a disconcertingly Brechtian work juxtaposing comedy and savagery.

Born in Guernsey, his actor-manager father Jack Wood stage-managed Laurence Olivier and John Gielgud’s overseas tours during the war. Charles grew up embedded in theatre before studying art and then enlisting in the army in 1950, leaving five years later, but remaining on the Army Reserve list. Before turning to playwriting, he worked as a scenic artist, cartoonist and copy artist, and backstage – most notably at Joan Littlewood’s Theatre Workshop with contemporaries Richard Harris and Dudley Sutton.

His plays regularly drew on his life: Fill the Stage With Happy Hours (Nottingham Playhouse, 1966) dealt with the theatre, and television’s Not at All (1962) with advertising. But the army provided his richest source material.

H, or Monologues in Front of Burning Cities (National Theatre, 1969) restaged the Indian mutiny on a huge scale, complete with a prosthetic horse and elephant. “It will never be done again, it cost too much,” Wood later reflected. Bawdy, brutal, historically grounded, it soared into flights of fantasy with extraordinary dialogue. “It should have been an opera,” he later said.

Wood also wrote films, among them the Palme d’Or-winning The Knack …and How to Get It (1965), the Beatles’ Help! (1965), How I Won the War (1967) and The Charge of the Light Brigade (1968).

The jarring tonal clashes, the compassion, fury and comedy, sometimes made Wood’s work a hard sell. But The Charge led to Veterans (London’s Royal Court, 1972), a play about actors in a period film, with Gielgud spoofing himself, helped by the unique cadences of Wood’s dialogue, every comma a springboard for its distinctive lugubrious sing-song quality, complete with dropped bricks: “You must be wanted on the field of battle; I’m not the least surprised, it’s complete chaos, they’re dragging in everybody.” Gielgud coined a term for Wood’s eccentric way with language: “Woodery-pokery.”

Film, theatre and television work continued to feed into one another. A rewrite of the 1970 movie The Adventures of Gerard inspired the teleplay A Bit of a Holiday, with George Cole in a naked self-portrait, which led in turn to a sequel and the sitcom Don’t Forget to Write! (1977-79). Red Star, begun as a screenplay to be shot “almost as a silent film”, morphed into a Royal Shakespeare Company production in 1984.

In 1988, his film Tumbledown won three BAFTAs and three Royal Television Society awards for its portrayal of an injured Falklands War veteran played by Colin Firth. The director, Richard Eyre, a longtime theatre friend, worked again with Wood on feature films including the Judi Dench-starring, BAFTA-winning Iris (2001).

Despite describing himself as “a recovering writer”, Wood never retired: he wrote every day until illness prevented it. He is survived by his wife of 65 years, the former actor Valerie Newman, and his daughter Kate, also a screenwriter.

Charles Wood was born on August 6, 1932 and died on February 1, aged 87.

East End hero Joan Littlewood brought back to life at the RSC

Latest Obituaries

More about this person

More about this organisation

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99