Fifty years of the revelatory Roundhouse

Arnold Wesker, in May of 1966, told The Stage: “Spirit is important.” The playwright was discussing plans for the Roundhouse, a new cultural hub in north London powered by the socialist aim of art for everyone. “It will be,” he continued, “a place of pleasure and marvellous revelation.”

Fifty years later, the Roundhouse has indeed provided plenty of both pleasure and revelation: seminal gigs, wild raves and circus shows have swung through, alongside numerous landmark theatrical productions, from Peter Brook’s deconstructed production of The Tempest in 1968 to the Royal Shakespeare Company’s epic Histories Cycle in 2008. Not, however, that it’s always been easy: this much-loved building has proved a major challenge to run.

The Roundhouse began life as a railway shed. When Robert Stephenson opened Britain’s first intercity railway terminal, Euston, he needed somewhere to store engines. Robert Dockray was commissioned in 1846 to build a “round house”; 160ft in diameter, the architectural landmark boasted an enormous turntable, which allowed trains to be spun into bays for servicing.

Obsolete by the 1860s, it fell out of use, but in 1869 the lease was acquired by Gilbey’s Gin. For some 90 years, the building was used to store its wares – before being filled with a very different kind of spirit.

Disgruntled by the cultural elitism of Britain, in 1960 Wesker lambasted the Labour movement for not supporting the arts. The Trades Union Congress in 1960 tabled item 42, which led to a resolution to support the arts. Wesker quickly created an organisation to take advantage of this, calling it Centre 42.

Seeking a base, Wesker persuaded clothing and property tycoon Louis Mintz, the owner of the then-empty Roundhouse, to give him a 19-year lease. Centre 42 soon garnered much high-profile support from the likes of Terence Rattigan, Benjamin Britten and Laurence Olivier. “There was agitation, a buzz in the air,” observed Wesker. “Other artists also wanted to find a popular audience.”

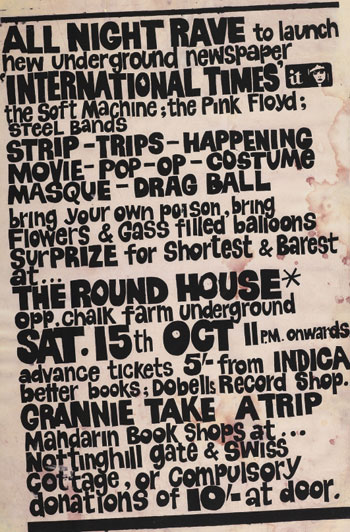

Even Harold Wilson held a tea party at Downing Street to help raise money; £400,000 was needed to realise the architect Rene Allio’s vision for the new Roundhouse. They managed it, and the Roundhouse reopened on October 15, 1966 for the launch party of underground newspaper International Times. That evening featured a fledgling Pink Floyd (who blew the feeble power supply), a Yoko Ono happening and a giant puddle of jelly. Marianne Faithfull won the best costume prize with a skimpy nun’s habit. Queasily, there were only two toilets for the 2,500-strong crowd; unsurprisingly, they flooded.

The venue also played host to the Doors, Jefferson Airplane, Jimi Hendrix and Led Zeppelin. But from the first, the Roundhouse was truly interdisciplinary. The theatre productions staged there in the 1960s have become, in their own way, as much the stuff of legend as the all-nighters.

Berkoff claimed the building called to him to ‘bring me your bizarre, your different’

In 1968, Brook’s The Tempest shook up what Shakespeare could be, scrambling the text and charging through the crowds on moving scaffolds. The Stage’s critic called it “theatre which is not theatre but is as exciting in atmosphere as any theatre could be” and grandly asked: “To what important things can this experimental group lead the changing theatre of the Western world?”

Other international innovators came, but didn’t always conquer. In 1969, revolutionary American company the Living Theatre brought four shows, none of which wowed critics. Still, Paradise Now ended with audience members throwing off their clothes and joining a conga down Chalk Farm Road. In the same year, Steven Berkoff staged his influential version of Kafka’s Metamorphosis, in which he hung upside down, bug-like, from scaffolding. Berkoff later described how the building seemed to call to him “bring me your strange, your bizarre, your different”.

But by 1970, Wesker was struggling with it. He felt abandoned by the unions and the Arts Council, and the finances were falling into disarray. He handed the reigns to George Hoskins, who, perhaps a little less high-minded, put on popular shows to help fund avant-garde offerings.

The Roundhouse was home to Kenneth Tynan’s succes de scandale, the nude revue Oh! Calcutta!, which in 1970 packed out titillated houses. The decade would see the acid era – at one Implosion club night, someone laced the wine with LSD – turn to punk, and the venue hosted the Ramones, Patti Smith and the Clash.

Inventive theatre still flourished: there was Andy Warhol’s play Pork, Buzz Goodbody’s studio-space Hamlet, and Peter Barnes’ production of Bartholomew Fair, which filled the former shed with pigs, geese and a donkey. The Roundhouse also became a welcoming home for regional theatre – even if critics have long maintained that the cavernous space is a nightmare in which to transfer plays.

Funding remained a very thorny issue. In 1977, Hoskins was ill and things were sliding off the rails; actor-turned-producer Thelma Holt was drafted in by the Arts Council essentially to sort the place out.

But foreign theatre and punk gigs didn’t balance the books. Holt grew tired of donning her wellies – either to wade through beer after gigs or to deal with the leaking roof – and financial woes. “I couldn’t get commercial sponsorship. I wanted to programme as I pleased and it wasn’t possible,” she has commented.

In 1983, the venue closed. A project for a ‘Black Arts Centre’ limped on for almost a decade, coming to nought except bitter controversy thanks to the millions ploughed into it. In the early 1990s, some 30 proposals for the building were considered by Camden Council, ranging from a discotheque to an archive for the Royal Institute of British Architects. None materialised.

Finally, in 1996, local businessman Torquil Norman bought the building and set up a charitable trust to return it to a performance hub. Marcus Davey was appointed chief executive in 1999, and Richard Eyre, a member of a rather starry board, called it a “building for the Millennium” in a piece in The Stage – perhaps cocking a snook at that other, less successful domed millennium project.

In 2004, a £30 million renovation funded by the Arts Council and the Heritage Lottery Fund, among others, was conducted by architect firm John McAslan, and Argentinian circus show Fuerzabruta reopened the iconic building triumphantly in 2006. The original impulse to programme widely – the RSC’s King Lear here, a Prince concert there – has been in evidence ever since.

But the venue also had a revised remit: to work with young people from all backgrounds. A decade on, an estimated 30,000 under-25s have been creatively involved. And they’ve certainly taken the venue to their hearts – during the 2011 riots, when 150 guests at a Ron Arad installation had to be locked in, young people came down to stand outside the building to protect it. The spirit Wesker had hoped to inspire clearly lives on.

If you’d like to read more stories from the history of entertainment, The Stage Archive offers access to all back issues of the paper from 1880 to 2007 and is available from £15

Latest Obituaries

More about this organisation

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99