Tim Bano

Tim BanoTim Bano is an award-winning arts journalist who has also written for the Guardian and Time Out, and worked as a producer on BBC Radio 4. ...full bio

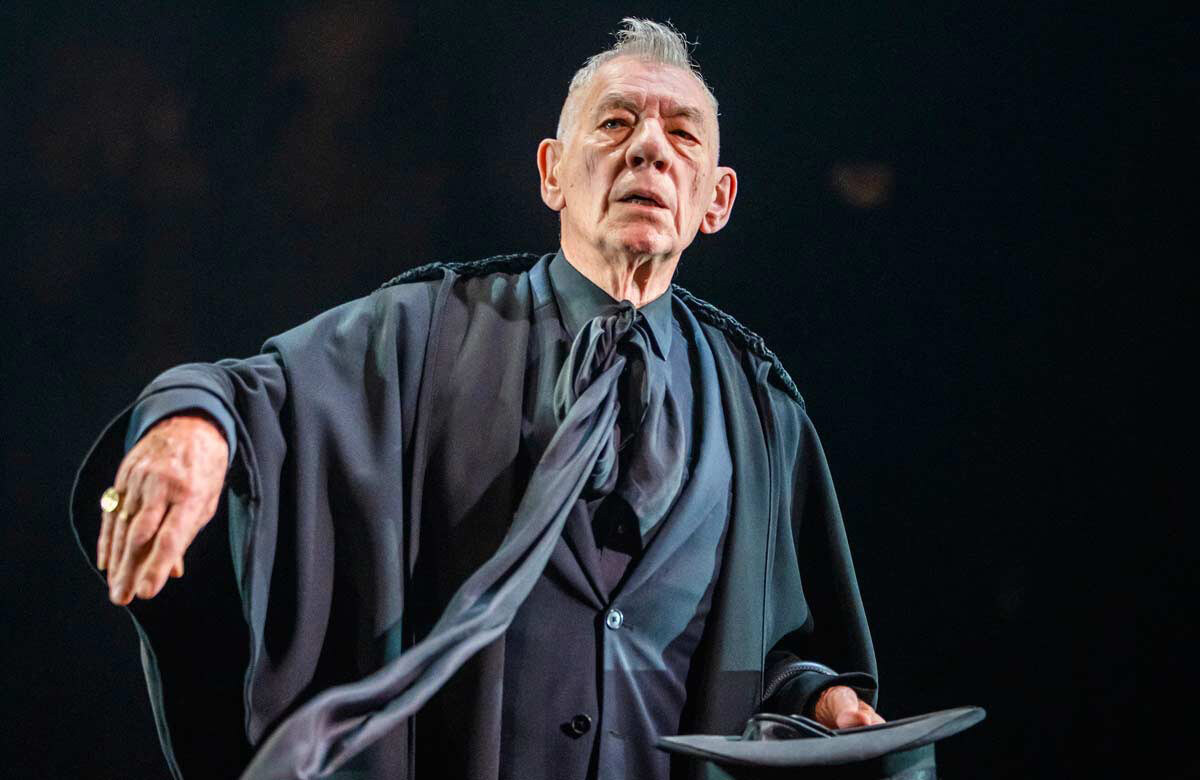

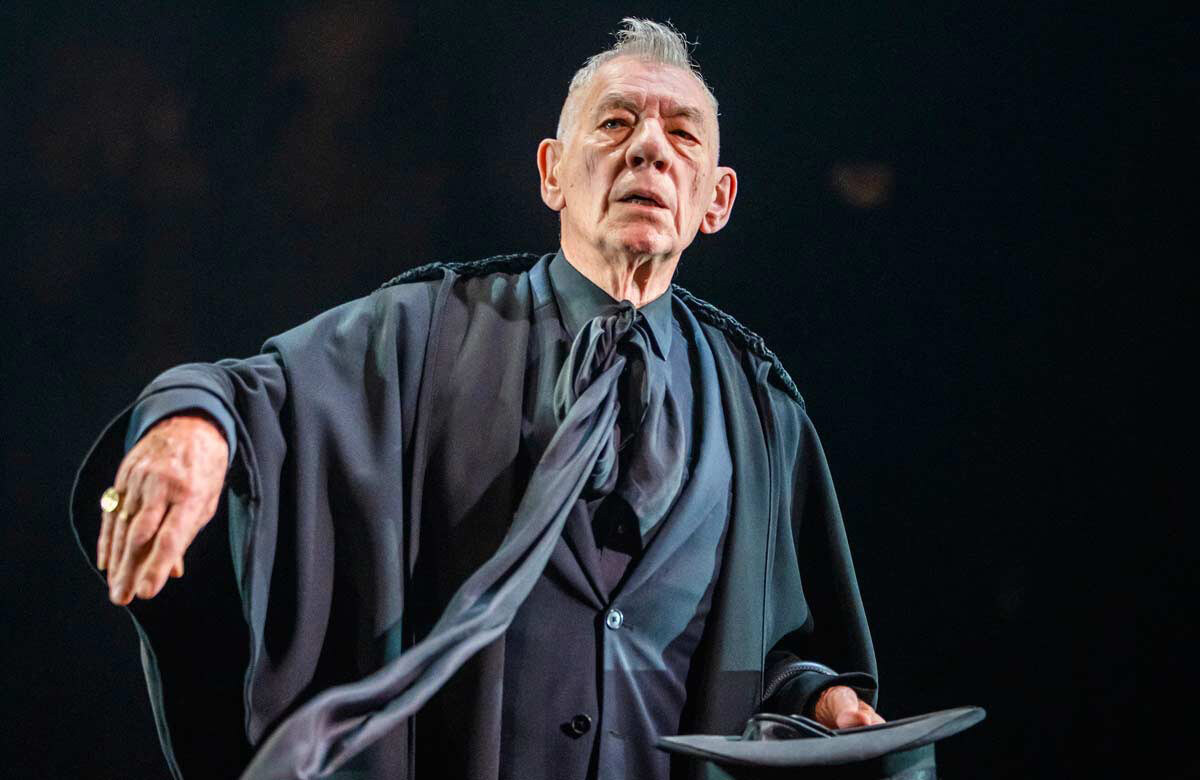

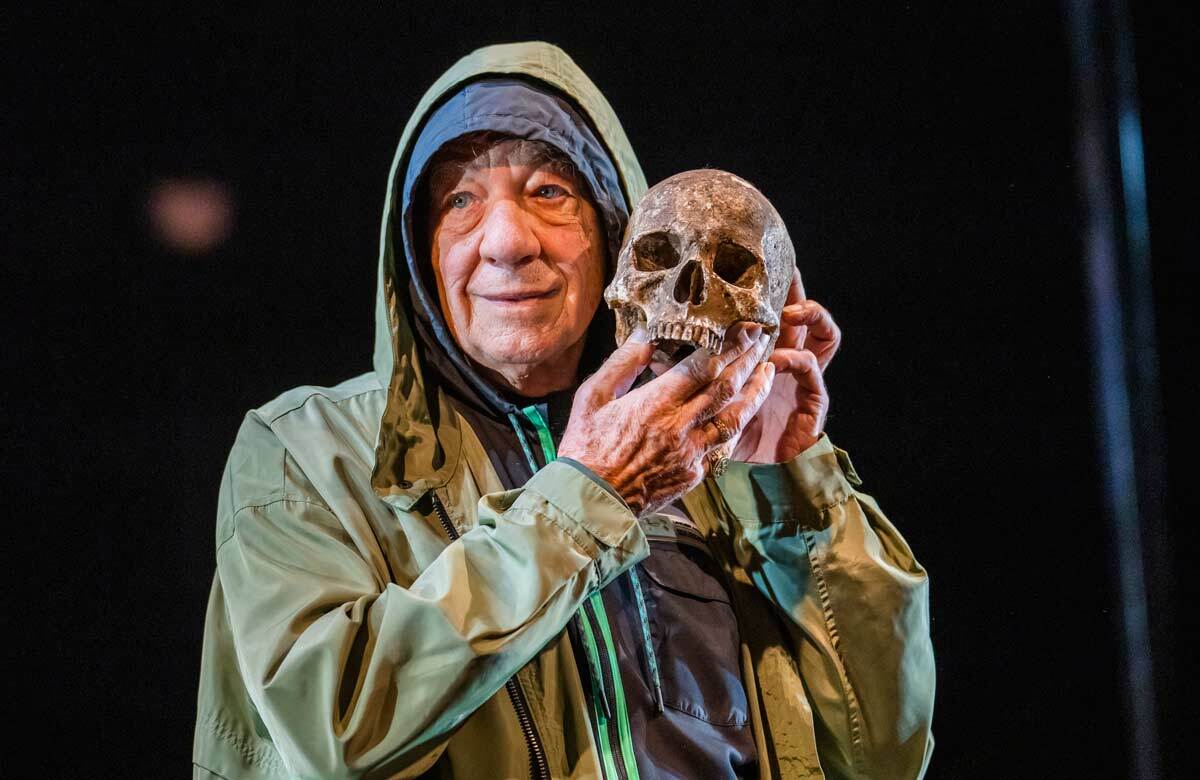

Ian McKellen entertains and entrances as Hamlet in an otherwise confused and chaotic production

What’s the opposite of Occam’s razor, the notion, crudely summarised, that the simplest idea is the best one? This hugger-mugger Hamlet is a tapestry (or should that be an arras?) of so many concepts and competing ideas that the end result is transfixing – if only for the moment of excitement between scenes when one wonders what jarringly incoherent concept could possibly come next.

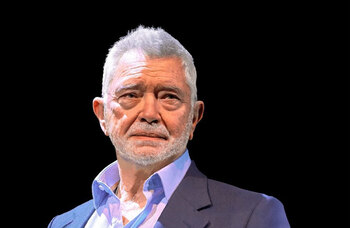

A proper old repertory-style company, in a proper old regional theatre: that’s the big idea of producer Bill Kenwright, director Sean Mathias and actor Ian McKellen. Veterans instructing newcomers, newcomers energising the vets. First up is a headline-hitting Hamlet, which would be attention-worthy alone for casting 82-year-old McKellen as Hamlet, half a century on from his last go.

McKellen and his co-stars Jenny Seagrove, Francesca Annis and Jonathan Hyde will return in October for The Cherry Orchard. Just add Agatha Christie’s Black Coffee and we’re back in the 1950s.

Opening the season with McKellen as Hamlet is a statement of intent. Age and gender confines will be shucked off. Not all of the publicity has been positive. Just this week, two cast members, Steven Berkoff (Polonius) and Emmanuella Cole (Laertes), reportedly left the production over a disagreement.

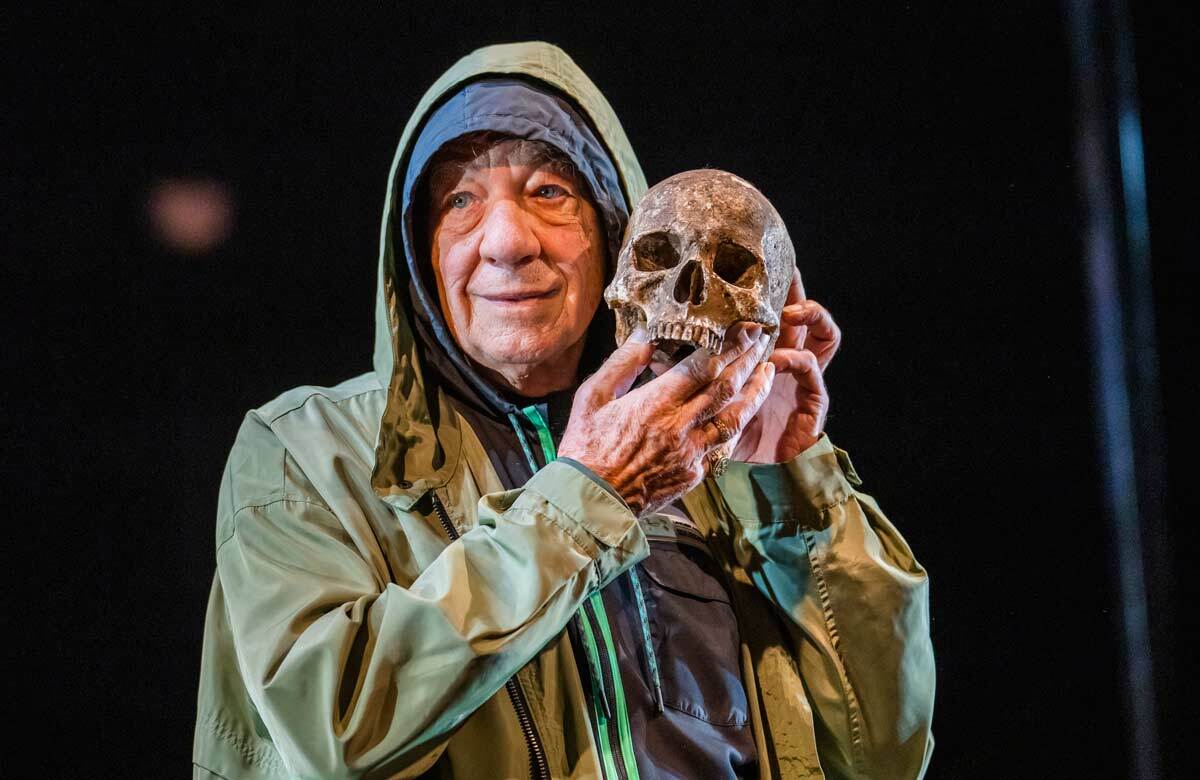

Over the past few months we’ve been teased with darkly lit shots of McKellen in a hoodie, not to mention a poster of the errant knight in terrifying, thin-rimmed sunglasses that make him look more of a Berkoff-esque villain than Berkoff himself. So the audience is primed for a production that promises to be radically gender-blind, colour-blind and age-blind (“Who is playing Gertrude?” quipped someone on Instagram, “Lillian Gish?”).

Though the production has been sold on its casting, we are being encouraged to ignore it. ‘What’s the big deal?’ they say, while flogging tickets on how big a big deal it is. So if we’re not to pay attention to age, gender, ethnicity and the way that lines take on new shade in unexpected mouths, then what does that leave us with?

A pretty messy production, it turns out. The age gaps and the occasional gender-swap are the least confusing thing about this production. Every scene flies off in some new direction. How about an angry folk ballad from Ophelia? Or a comical Welsh gravedigger?

Designer Lee Newby’s Elsinore is a black space cut through with a gantry walkway, the one constant in a production that otherwise refuses to settle. Odd performance choices abound. Francesca Annis, despite her excellent ability to make sense of a line, goes full panto as the ghost of Hamlet’s father. They might as well have stuck a white sheet over her head. Seagrove adopts an odd accent as Gertrude, which comes from no discernible nation on this planet.

It’s the latecomers to the cast, surprisingly, who work best: Ashley D Gayle’s last-minute Laertes impresses with his zeal, foregrounding his character’s commitment to principle, and Frances Barber finds humour in Polonius’ stern officiousness and propensity for wanging on.

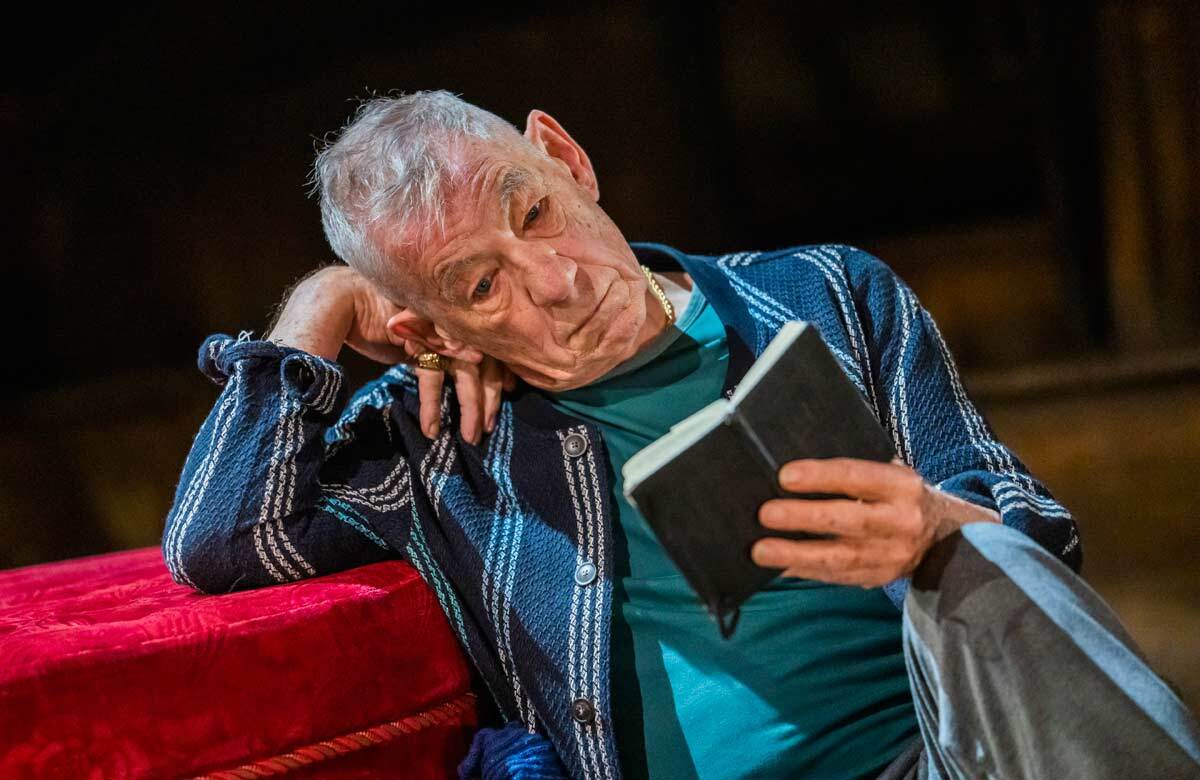

And what of McKellen? He has a very particular way with Shakespeare. He combines a deep understanding of the words with the spontaneity of taking each line as it comes.

He favours natural patterns of speech over the strictures of metre, which gives his words a comforting rhythm. But he lays flighty, unexpected melodies over the top, his intonation pitching from octave to octave, from growl to shriek in an instant. He lingers occasionally on long, whistling sibilants or high, tremulous exclamations, listening to the sounds die in the air.

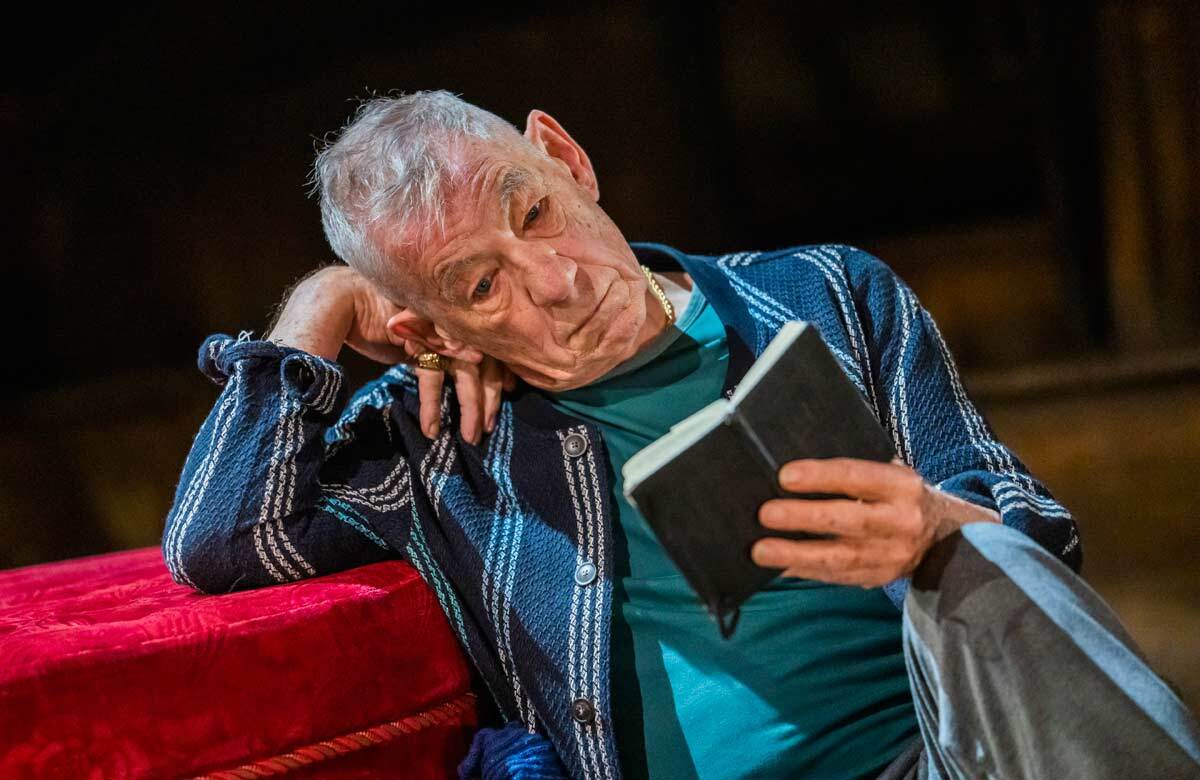

It doesn’t matter whether he is believably a young man (he’s not, really) – simply being on stage seems to whip away 30 years, and he bounds and scampers admirably, his gestures wide and deliberate, like Keaton or Chaplin, or some other silent-movie jester.

McKellen’s Hamlet is deliberately our friend. He draws on all his grinning charm to chat his way into our confidence. He’s not mad, that’s perfectly clear – except for when he is. Because there are two moments when this scheming scamp of a prince loses control. First, in his confrontation with Gertrude, thrusting himself into Seagrove’s face to hiss and shout. Second, at Ophelia’s graveside, where he breaks down. Suddenly, the stiffness and careful precision fall away. It feels real and dangerous.

But still we rub up against the problem of how much we are meant to ignore his age. Because, not to be too morbid, there is naturally a sharper resonance to the lines about mortality. “When you’re my age,” McKellen said recently, “I think about dying every day of my life – and so does Hamlet.”

Although "to be or not to be" comes and goes with no great fanfare, insight comes from different places: “If it be not now, yet it will come. The readiness is all,” he says as he walks off to face probable death. He states it simply and gently, with the wise smile of a long-lived life. It’s very moving.

The rest is chaos. None of the actors seems to be in the same production. Between harsh music cues and strange costumes, outrageous wigs and extended mimes, it’s impossible to work out if there’s a big idea here. “We live in a time of immense confusion”, says Mathias in a programme note. The production certainly reflects that. Perhaps it’s deliberate, perhaps not.

But once you stop trying to find the answer and accept that there are only, in this Elsinore, ever more bewildering questions, the evening unfolds entertainingly enough. After all, with all its throwbacks to old-style rep, the last thing anyone expected was the unexpected.

More about this organisation

More Reviews

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99