Satyagraha director Phelim McDermott: ‘Sadly, there won’t ever be a moment when this opera isn’t relevant’

With a body of experimental work behind him, the maverick director and founder of Improbable has embraced opera and is helping lead the discussion of theatre’s future as well as mentoring the next generation. He tells Lyn Gardner why industry leaders must hold their nerve to drive change in the wake of harassment allegations

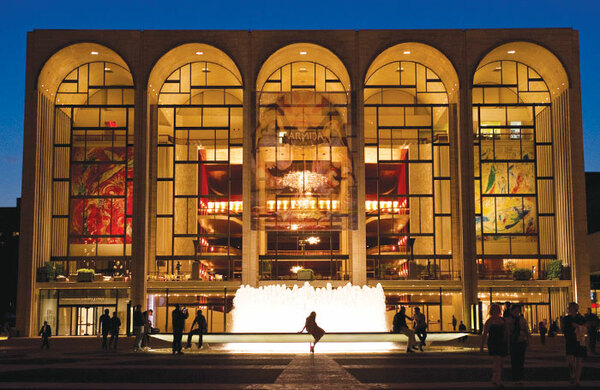

Not many people can be found directing at the Metropolitan Opera in New York one week and appearing as a guest improviser on the stage at the Comedy Store in London the next. But then Phelim McDermott’s theatre career has never followed an obvious path.

He’s as comfortable directing Jim Broadbent in A Christmas Carol for Sonia Friedman in the West End – in 2016 – as he is helping Liverpool theatre company 20 Stories High create devised show She’s Leaving Home with teenagers. He is also actively engaged with Devoted and Disgruntled, the annual Open Space event founded by his company Improbable, in which theatre checks in with itself. McDermott practises both on the inside and on the outside: he is a theatre elder and yet, in some senses, he remains an enfant terrible.

“Opera has a certain cultural status and if you direct one then status is conferred. But I still love improvising at the Comedy Store and making small-scale shows, and I can’t imagine a time when I didn’t have a foot in both camps,” he says.

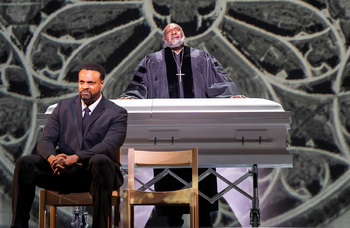

The day before this year’s Devoted and Disgruntled, we’re sitting in 3 Mills Studios in east London, where McDermott is rehearsing the revival of Philip Glass’ Satyagraha. It marks a return to the very first opera he directed for English National Opera 11 years ago. He isn’t worried that a show exploring the world’s political and religious problems may have dated.

“Sadly, there won’t ever be a moment when this opera isn’t relevant,” he says. “It’s one of the things I love about it. When we did it in New York, the Occupy Wall Street protests were going on and it felt as if it was reflecting that. The nature of the piece is that there is so much space in it and the images we’ve created are so open that people can always project on to them.”

Taking its name from the Sanskrit word meaning ‘life’ or ‘love-force’, Satyagraha follows Mahatma Gandhi’s early years in South Africa as he developed non-violent protest as a political tool. It is a strange, almost hallucinatory experience, one that requires an act of surrender on the part of the audience.

“With everything in the news at the moment I think we need Satyagraha more than ever. The idea of love’s force is not a fluffy ‘new agey’ thing. It’s hardcore. Gandhi didn’t avoid conflict, he recognised that it is part of the world. But he did want to take that conflict and use it differently. Satyagraha is about stepping into conflict and changing the world through it.”

Now in his 50s, and with several operas successfully under his belt, McDermott still has an impish quality both in his looks and his ability to surprise audiences and himself.

I thought opera would be alien to me, but actually it’s like doing a great big site-specific gig

“Is it a surprise to find myself directing operas? Yeah, it is,” he says. “I never thought that I would get as interested in opera as I have. I thought it would be alien to me, but actually it’s just like doing a great big site-specific gig. I love working with opera singers and I think they enjoy working with me because I love the theatricality, the big pictures and the big acting.”

Breaking boundaries

Looking back over his career, McDermott says there was always a strong musical sensibility to his work. Gaudete, based on Ted Hughes’ poem and one of his first shows made after graduating from the then Middlesex Polytechnic in the mid-1980s, “was operatic in scale”.

He adds, a little wistfully: “Nowadays, because of funding and the need to do co-productions, I seldom get to do big theatre shows, so it’s exciting to be able to do something on this scale.”

McDermott is the co-founder of Improbable theatre company with visionary designer Julian Crouch, director and improviser Lee Simpson and producer Nick Sweeting.

The company’s work has spanned small shows such as 70 Hill Lane, about McDermott’s teenage experiences in a haunted house, Coma, exploring the inner lives of patients in near-death states, and most recently Lost Without Words, a show created at the National Theatre last year encouraging older actors – who may find learning a script a problem – to improvise.

But there has been much larger-scale work too, a lot of it just as boundary breaking. McDermott has never allowed himself to be pigeonholed in a career where the greatest hits have spanned the monstrously enjoyable 1998 junk opera Shockheaded Peter, inspired by Heinrich Hoffmann’s scary cautionary tales, and one of the UK’s greatest ever outdoor shows, Sticky in 1998, which was made with much-missed pyrotechnic specialists the World Famous.

To add to his versatile repertoire there was Theatre of Blood, co-directed with Simpson, a stage version of the 1973 cult comedy movie in which theatre critics are dispatched by a vengeful actor incensed by his bad reviews. Another notable show was 1996’s award-winning A Midsummer Night’s Dream in which the forest of Arden was conjured entirely from sticky tape.

Satyagraha also features sticky tape – together with newspaper, which is something of a recurring motif in McDermott’s shows and was used as an improvisational material in the object-manipulation work Animo.

Newspaper and tape are not materials that are generally found in the world’s great opera houses. McDermott admits there were raised eyebrows at the ‘talk through’ on the first day of rehearsals of Satyagraha more than a decade ago, when he and Crouch announced that Act III would probably involve lots of sticky tape but they hadn’t yet decided in what way.

“We had to dare ourselves”, recalls McDermott. Though, he adds, the struggle to keep daring after the Olivier-winning production of Glass’ Akhnaten as well as Coney Island-set Cosi Fan Tutte at the Met became easier.

“Of course you do get braver, and with success you earn the right to play the role of the crazy director who does strange things and brings newspaper and puppets and jugglers into the rehearsal room. Some people just go with it but sometimes there is a resistance. If you create a good atmosphere and treat people well, then you almost always get good work out of them.”

Checking in to ensure everyone in the room has both a voice and agency is very much a feature of McDermott’s work. He has a magpie inquisitiveness, alighting on the things that interest him and spinning them into theatrical gold.

Continues…

Q&A: Phelim McDermott

What was your first non-theatre job? Painting and decorating. I spent a long summer painting my agent’s new office.

What was your first professional theatre job? I transitioned from performing Cupboard Man at the National Student Drama Festival to Edinburgh to the Almeida – a crossfade into the profession.

What is your next job? Directing Cosi Fan Tutte at the Metropolitan Opera in New York.

What do you wish someone had told you when you were starting out? Remember it’s a novel, not a short story.

Who or what was your biggest influence? Reading Impro by Keith Johnstone, then working with him in 1985.

What’s your best advice for auditions? The bit just after you finish your song or speech is the most revealing moment of the audition for a director.

If you hadn’t been a director, what would you have been? I’d have become a special effects technician.

Do you have any theatrical superstitions or rituals? Doing a check-in for the whole company (whoever is in the room) at the start of each day. Creating circles of chairs, not rows of desks, wherever possible.

Influences and techniques

The work of improvisation guru Keith Johnstone has been a strong influence on McDermott, though he points out that, for all its joys, “playing can be hard work”. He is a fan of the late Michael Chekhov – nephew of Anton and viewed by Stanislavski as his most brilliant student – who founded the Michael Chekhov Theatre School at Dartington Hall in Devon in the 1930s.

McDermott often uses Arnold and Amy Mindell’s ‘process-orientated psychology’ techniques developed in the late 1970s to facilitate work both in rehearsals and workshops.

Both his theatre – particularly when working with actors on Shakespeare – and opera work borrow from the techniques developed by the late H Wesley Balk, who invented a system that looks at body, emotion and voice separately.

“Most actors and singers have a vocabulary of only five or six gestures. What Balk’s system does is push the spectrum of possibility. As the performers get to the edge of their skill levels, they immediately become interesting to watch because they start exciting themselves; so we are excited to watch them.”

He says that he has got braver at using such techniques with opera singers. “Generally, opera directors come into the space and say ‘stand here’ or ‘walk over there’, but I try to expand that. It tends to freak the performers out a bit at the start because it means that I am giving them the space to make decisions and they are not used to that. They are more used to being told what to do, but what I try to do is widen the possibilities of the decisions they might make and then let them decide.”

McDermott knew as young as seven that he wanted to be an actor. He was born and raised in Manchester, and would head to the city’s Royal Exchange theatre with his English teacher mum for fun. With his parents supportive of his artistic leanings, but also keen that he get a degree, he went to what was then Middlesex Polytechnic, where he studied under John Wright, who went on to found Told by an Idiot.

It was a course that turned out collaborative theatremakers rather than just actors and directors and, early on in his career, he realised that he was as interested in process as he in product. It may partly explain why he was sacked from the Broadway show The Addams Family musical shortly before it opened in 2010, even though it showed good signs of being a success. That was a rare moment of humiliation in a career that has often seemed blessed.

Continues…

Phelim McDermott in quotes

“Looking back, the shows I’ve enjoyed making are those slightly outside my comfort zone. Those are the ones from which you really learn.”

“Not knowing in a rehearsal room is a good place to be. It can be a sweet spot from which something interesting happens.”

“A lot of things happening in the world make people say, ‘My vote doesn’t mean anything so why should I bother?’ At Open Space, you say this thing out loud that worries or concerns you and it turns out there are 10 others who really care about it too when you thought you were the only one.”

“Those arguments that pit plays against devised work are never going to go away. But now there is an established culture of devising theatre in a collaborative way, just like Shakespeare used to do. You are not telling me those Shakespeare shows weren’t devised.”

“Some days I’m disgruntled by theatre and some days I reconnect to my devotion to it. You are suddenly surprised by something that moves you. I do love it, or I’d be doing something else.”

From theatremaker to mentor

In his final term at Middlesex, McDermott teamed up with Julia Bardsley to make Cupboard Man, based on the Ian McEwan short story. It was a success at the National Student Drama Festival and went to Edinburgh, where it was spotted by Pierre Audi, who was then running the Almeida and brought it to London. Audi supported subsequent work including a memorable version of Edward Gorey’s The Vinegar Works.

It was a dream start in the industry. “We almost didn’t break step,” recalls McDermott. “We were so supported.” He also acted, playing minor roles in the movies The Baby of Macon and Robin Hood, and working on several Richard Jones shows at the Old Vic, including 1988’s Too Clever by Half starring a young Alex Jennings. He’s well aware that few of today’s practitioners are so lucky.

“It’s such a different landscape from when I was starting out and it is a lot tougher now. I am constantly amazed by young theatremakers and how, when it’s such a difficult funding climate and there are so many of them and so few opportunities, they keep on doing it. But they do.”

McDermott and Improbable have been doing their bit to help through mentoring but particularly through Devoted and Disgruntled, which uses the tools of Open Space, created by Harrison Owen, to support groups to self-organise and collaborate around any question of shared concern.

There is often a misunderstanding from those who have never been to Devoted and Disgruntled that it is a talking shop for those in the independent sector. In fact, it is a place for anyone, in any role, working in any part of the industry, who is keen to take responsibility for instigating change.

Numerous projects have started at D&D, friendships have been formed, collaborations created and work secured. Many current debates in theatre have first been aired in D&D discussions – particularly around access and diversity.

Improbable is as much known for D&D and facilitating discussion about theatre as it is for making theatre. McDermott reckons that, 13 years on from the first D&D event, it is still much needed.

“We have a commitment to just keep doing it in the belief that if we do keep doing it the culture will start to change,” he says. “It may not get recognised for doing that, but we think of it as being like tilling soil.”

Addressing harassment

McDermott believes D&D has a more crucial role than ever in the wake of allegations in the theatre industry of sexual abuse, harassment and bullying.

“I’m convinced that some of the things that have happened in those companies and buildings with hierarchical structures might not have happened, and the voices not silenced or marginalised, if the principles of Open Space, which supports voices on the edge to be heard and have agency, had been used.”

He also predicts that unless the structures of theatre and the way it is organised are rethought and re-imagined, such abuses will inevitably occur again.

“It’s great to get rid of these people who have behaved badly, but getting rid of a few people doesn’t make the problem go away,” he says. “Until you change the culture, it will just happen again. Those relationships to power need changing because theatre doesn’t work as effectively as it could in terms of how we communicate with each other and how we support difficult conversations to happen.”

He continues: “There will only be real change if people take on board that it is not just the people and the roles that need to change, but all the systems and the whole culture. Those old power structures are crumbling, and that means finding new ways of everyone taking responsibility for how a building, a company or a rehearsal room is run and ultimately how theatre is made.”

McDermott applauds industry leaders such as Vicky Featherstone at London’s Royal Court and Rufus Norris at the National Theatre for genuinely trying to bring about a culture shift, but he acknowledges how difficult it is.

“People like Vicky are trying to break down the old systems but if you go into those buildings, you have to step into the old system to begin with and break it apart, and that’s a hard thing to do.”

As funding gets tighter, change gets harder. “There is a danger that people feel that we don’t have time to change things and can’t afford to take that risk to work differently. But we must. I have such admiration for people like Rufus Norris who is trying at the NT,” he says.

“But deep change doesn’t happen overnight. You have to go through a period when some stuff isn’t going to work. That’s when you really have to hold your nerve.”

CV: Phelim McDermott

Born: 1963, Manchester

Training: Middlesex Polytechnic

Awards: Time Out director of the year award for Gaudete (1986), Time Out award for best Off-West End production for 70 Hill Lane (1997), Obie for best Off-Broadway show for 70 Hill Lane (1997), Barclays Theatre Award for best touring production for A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1997), Barclays TMA best director award for Shockheaded Peter (1998), Olivier awards: best entertainment for Shockheaded Peter (2002); best new opera production for Akhnaten (2017)

Agent: AHA Talent

Opinion

More about this venue

Opinion

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99