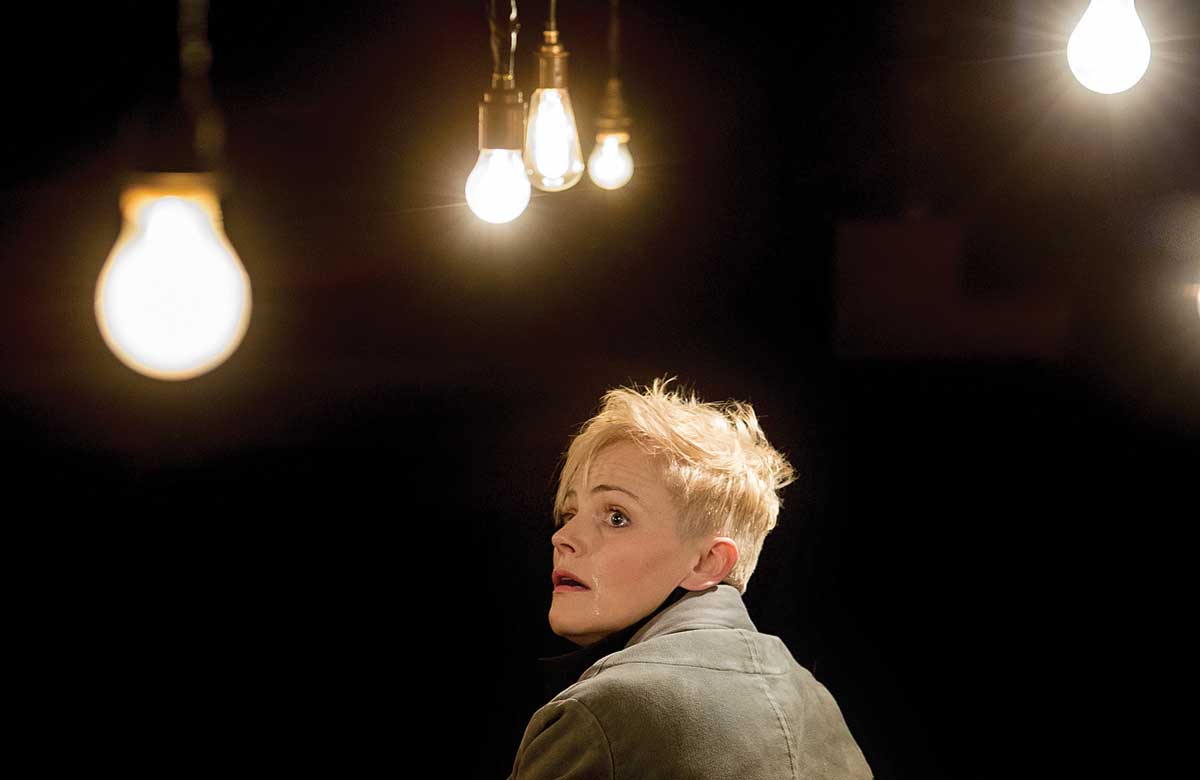

Sarah Frankcom

Lyn Gardner

Lyn GardnerAfter great success as Manchester Royal Exchange’s artistic director, Sarah Frankcom is leading one of the most prestigious drama schools in the UK. She tells Lyn Gardner about undergoing a process of ‘unlearning’ for staff and students, breaking the hold Stanislavski and Chekhov have had over drama schools and how 2020’s cohort of students differ from previous years

Sarah Frankcom, the former artistic director of Manchester’s Royal Exchange, says she sees her role as the new director of LAMDA as “leading a process of unlearning”.

This means that when the new intake of students arrive at the drama school at the end of the month, she is contemplating welcoming them by saying: “We don’t know anything.” And: “Training is not us giving you something. Your training is how you apply yourself to the processes we have set up and we will learn together. All the people I’ve gathered to teach you are here because they truly believe that learning is a two-way thing, and we have lots to learn from you and everything that we do will be co-created. We will do it together.”

Doing it together and admitting you don’t have all the answers has always been Frankcom’s philosophy, whether running a large regional producing theatre, a small meeting or a rehearsal room. Her time at the Royal Exchange included an ongoing initiative called You, the Audience, which was about listening and responding to the hopes and needs of the people of Manchester.

Early in her career, she found herself, a young working-class director, at London’s National Theatre Studio faced by a group of established actors who demanded she tell them what to do. They berated her for sitting on the floor because it demeaned the status of the director as all-knowing. She found the episode devastating at the time.

Unlearning

Theatre no longer subscribes to the idea that a director should arrive on day one with all the answers, and Frankcom is adamant that UK drama schools and teachers need to rethink the best ways of learning for many different students from many different backgrounds. She believes it’s time we accepted “there is nothing mysterious about acting, we need to demystify it”. For Frankcom “the idea of the student taught by a guru is not helpful at all, it needs to be thrown away”. All the more so in the era of #MeToo and Black Lives Matter.

‘As our cohorts change, our approach has to be more bespoke to the students we are training’

Frankcom recognises that some might see an irony in the concept of unlearning, given that LAMDA, the UK’s oldest drama school, has a reputation as one of theatre’s most august places of learning, with a glittering list of alumni to match, including its current president Benedict Cumberbatch. But she is certain it’s necessary and urgent, not only because she believes “there has been a disconnect between how theatre works now and how drama schools work. Schools are way behind”, but also because of the pandemic.

“Producing theatre is facing an existential and practical crisis. It is the biggest crisis it has ever faced and that has massive implications for young people coming into our training organisations. More than ever we need to be asking: ‘What are we training them for?’ and ‘How are we training them?’ Currently the industry is almost standstill and artists find themselves in the most vulnerable place ever, and that’s scary. So, we have to be honest with young people, who are arriving for training, about where we are at. We have a responsibility as training organisations to ensure we put in place the best set of experiences that will prepare them for the realities of the industry and really support them to develop as artists.”

Despite the pandemic, the whirlwind of activity Frankcom brought to LAMDA when she arrived on the Talgarth Road in 2019 hasn’t stopped. She joined the drama school after 21 years at the Royal Exchange, where she was first literary manager, then joint artistic director and from 2014 to 2019 sole artistic director. During her solo tenure the theatre grew into one of the most exciting producing theatres in the UK. Frankcom, her team and her actors won a stream of awards while demonstrating that it was possible to be fully embedded within the community, operate a radical programming policy and still fill a 750-seat theatre every night to accommodate what she describes as “the tyranny of the box office” – the challenge every producing theatre faces.

Frankcom had a reputation for listening and being decisive. She also admits when she gets things wrong. Such was the case earlier in the year when, following criticism, she released a statement admitting she and LAMDA had been slow to respond to the death of George Floyd and the Black Lives Matter movement.

“If the leadership isn’t honest and doesn’t own its failings then there is no way forward. It’s important when you’ve been called out on something to own your own racism. The painful experience we have been through comes from the fact that when moving to a place where anti-racism is part of everything you do, the first stage of that has to be to accept that we are racist and racism is a system. It is an uncomfortable place to put yourself in, but it is vital if a predominantly white organisation is going to do that work.”

She says the biggest question facing any training organisation is the curriculum and “the conversation around decolonising the curriculum is a very urgent and nuanced one that can’t just take place internally”.

A fierceness lurks under Frankcom’s quietly spoken, almost shy, persona and she has always exuded an integrity that comes from not being clubbable. “The clubbiness of theatre is the bit I’ve always liked about it least. It continues to be a club – a club I never felt I was in.” Or wanted to be in. There is a strength in that.

Manchester

In her early days as a teacher turned director – her parents agreed to her studying English and drama at Westfield College only if she subsequently attained a PGCE – she wasn’t particularly confident and “being in one building and one city for a really long time allowed me to get to know the audience and the people of the city really well. All I did was think about them and shift the lens to them so that, as a theatre, we were always asking: ‘Who are we, who do we want to be and who are we here for?’”.

It brought creative benefits. Her production of Hamlet with Maxine Peake – with whom she has built a hugely rewarding creative partnership over many years – was extended; her award-winning revival of Our Town in 2017 spoke directly to a city still raw from the Manchester Arena bombing. There were sleepovers for audiences in the theatre, intergenerational shows made by the Elders and Young companies, and an increasing understanding that theatre is made with people, not just for them.

CV Sarah Frankcom

Born: Sheffield, 1966

Training: English and drama degree at Westfield College, London

Landmark productions:

• Confetti, Ovalhouse, London (1992)

• 23.58, Sheffield Crucible (1999)

• Across Oka, Royal Exchange Theatre, Manchester (2003)

• On the Shore of the Wide World, Royal Exchange (2005)

• Christmas Is Miles Away, Bush Theatre, London (2007)

• The Five Wives of Maurice Pinder, National Theatre, London (2007)

• Punk Rock, Lyric Hammersmith, London (2009)

• Orpheus Descending, Royal Exchange (2012)

• The Masque of Anarchy, Manchester International Festival (2013)

• That Day We Sang, Royal Exchange (2013)

• Hamlet, Royal Exchange (2014)

• The Skriker, Royal Exchange (2015)

• The Last Testament of Lillian Bilocca, Hull City of Culture (2017)

• Our Town, Royal Exchange (2017)

• Happy Days, Royal Exchange (2018)

• West Side Story, Royal Exchange (2019)

• Light Falls, Royal Exchange (2019)

Awards:

• UK Theatre award for best director for Our Town (2018)

Agent: Mel Kenyon at Casarotto Ramsay and Associates

Her motto is: “Change doesn’t happen through talking about things, it happens by doing things,” and she has been decisive since arriving at LAMDA. One of her first moves was to slash audition fees, and another was to talk extensively to former and current students about their experiences at LAMDA. As a result, the audition process has become far more transparent, ways of working within the school have changed – no more 9am to 9pm days that leave students exhausted and don’t reflect best practice in the industry – and there is a developing anti-racism action plan, which Frankcom describes as “a living document” to which everyone in the school and former alumni can contribute. LAMDA is also going through a process of restructuring that won’t be complete until early next year. The aim is to better serve student needs and the needs of a changing industry, but also to future-proof itself in the light of the pandemic.

“Half of LAMDA’s business is from its exams. It is a learning business and it has been hit by the pandemic but it is that business that subsidises the drama school, so restructure is necessary so we can get all our resources into a place where we can work them as hard as we can.”

Initiating change

But the restructuring is about far more than financial necessity. “Undoubtedly, in part due to the pandemic and Black Lives Matter, a lot of things have been working themselves loose that pose big questions to training institutions and how we operate and the experiences of people who have passed through those schools and felt their class or race has not been acknowledged in the curriculum and training,” she says.

“It is not easy to take an organisation forward when its traditions of training are based and rooted in some almost sacred ideas: the dominance of Stanislavski, the importance of Chekhov. These things need to be reviewed and challenged because they’ve been very present for a very long time. Do they still serve? We need to look at who we are training, how we are training them and what is relevant now. It is exciting but dismantling is difficult too. Many people are resistant to change, they like things to stay the same. Sometimes it can feel particularly difficult when on a daily basis we are all living through a changing world. But you can’t not do it because it’s difficult.”

‘There is nothing mysterious about acting, we need to demystify it’

Nonetheless, there is pain involved in any restructuring process, particularly when it includes jobs losses as is happening at LAMDA, and Frankcom is well aware of the hurt that comes with that. She recognises that many teachers “have given massive service to the school” and “have loved their students” but argues that “as our cohorts change, our approach has to be more bespoke to the students we are training”. The coming year’s intake is, she says, substantially different from previous cohorts and she puts that down to greater transparency and an audition process that was very different. “An awful lot of them have very little experience. They have not done drama at school or been part of youth theatres.”

Because of a changing student intake, Frankcom says the school has “a lot work to do around staff development”. She continues: “The idea that you can deliver the same training to different groups is no longer right. We need to understand what the specific needs of the students are, and that means having a staff who, as well as teaching, have more responsibility for development of the curriculum, the delivery of anti-racism teaching practice, and working across access, participation and artist development.

“Something helpful to think about in terms of the restructure is that it will bring us more consistency in terms of our teaching staff – the chance to train ourselves properly, whether that’s unconscious-bias training or properly developing a way to work with D/deaf and disabled actors. We’ve not had a structure that allows us to do that in a way that needs to be done today.”

But the restructure is not about disrespecting the past or making change for the sake of change. “What I’m trying to build at LAMDA is a model of collaboration and co-creation that reflects theatre today. If we really want sustained change in our industry the best way to achieve it is through empowering young artists through training. For too long we’ve been developing artists who have been grateful for the jobs they’ve received, and been in awe of hierarchies and the power of the director. We have to do things differently. If we train empowered young artists who demand to work in a certain way, that’s potentially exciting and transforming for the industry. Do we want to be an industry that waits around for change to come from the artistic director of the National Theatre?”

The confidence of youth

Frankcom’s own experience as a drama teacher makes her a good fit for the LAMDA job, as does her experience of running a big producing house, but what really made her interested in the move from Manchester to the Talgath Road were her experiences in the rehearsal room.

“I worked with a lot of young actors on their first or second jobs, including with a lot of young actors who had not trained at all, and the question I found myself asking was: ‘Why is it that the ones who haven’t trained are often the most fearless and instinctive in a rehearsal situation and don’t think there is a right or wrong way to do things but just throw themselves at it? Why are they so much more confident than the ones who have trained at prestigious schools?’”

She thinks the answer lies in the nature of the training that has been offered for so long, and its one-size-fits-all approach that may not reflect the experiences and needs of young people today.

“There is a more profound conversation to be had around how learning happens. I believe people don’t train to become actors – they are actors when they arrive in a drama school. The training should be giving them a series of experiences and processes that make them understand more about who they are as an actor and allow them to gain confidence and add to what they can do. Often training has felt like something that takes things away from people.” Instead she wants LAMDA to deliver training that supports young actors’ journeys towards self-expression as artists and their confidence in making and self-creation.

Q&A Sarah Frankcom

What was your first non-theatre job?

As a waitress in a Sheffield hotel.

What was your first professional theatre job?

As an assistant director at the National Theatre. I’d not been in any theatre system, so I didn’t know what was expected of me or how it worked.

What do you wish someone had told you when you were starting out?

Make sure you always treat people as you would like to be treated.

Who or what was your biggest influence?

The playwright Robert Holman. He was the first significant playwright I ever met and he offered great friendship and encouragement. I learned a lot about how plays work from him.

If you hadn’t been a director, what would you have been?

I’d have happily continued being a drama teacher.

“The thing that’s been really interesting for me is seeing the impact on our graduating students when they have been empowered with dramaturgs and makers to make their own work and tell their own stories,” Frankcom says. “They have made some interesting and original work, but it’s also had an impact on their freedom and confidence as actors. There seems to be a relationship between feeling you can articulate and express something about yourself and how that makes you more confident about being in other people’s stories. You can work from yourself more confidently.”

There is much more work to be done. Frankcom would like to see many more over-25s in training, arguing that life experience is important for actors, and she wants to make LAMDA a better resource for those who live on the doorstep, and do more outside London because “any drama school in London needs to grapple with the fact that for lots of people, coming here to train is prohibitively expensive so they need full scholarships”. She also believes that there isn’t enough sharing of practice between schools.

There was a time when moving to a drama school was seen as the point when a career slowed down. But what Frankcom represents – along with Orla O’Loughlin, who now heads up Guildhall after several years as artistic director of the Traverse in Edinburgh – is a new breed of drama school leadership. One that wants to see training constantly evolving and responding to a changing world and industry, and one that is still completely in touch with theatre and attuned to its shifting needs. Both Frankcom and O’Loughlin will continue to make work outside of their respective schools.

In fact, Frankcom thinks the time is long overdue for drama schools to see themselves not just as training establishments but as creative organisations that have a far wider role to play. “When I came here, I realised two very stark things. I had the same budgets I had in Manchester at the Exchange and I was probably employing the same or more freelance artists. So recognising a drama school as a creative place and as a home for artists feels crucial. And that means not looking at those artists as people who come in and serve the mission of training but looking at how they can have – over a period of time – a more involved relationship with the school and the students. That’s the way forward. It’s about the door being more open in every way.”

Big Interviews

Recommended for you

Opinion

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99