Liz Hoggard

Liz HoggardIt is hard to find an area of the entertainment industry that Es Devlin hasn’t worked in, having designed sets for shows ranging from The Lehman Trilogy to Beyoncé’s Renaissance tour to the Super Bowl half-time show. She tells Liz Hoggard about her career journey and the importance and future of design

The term ‘set designer’ really doesn’t do justice to Es Devlin’s talents. She has created stages for everyone from Lady Gaga to Louis Vuitton. She sent Miley Cyrus down a tongue-shaped slide and conjured a rotating cinema for Beyoncé. She designed the London 2012 Olympics closing ceremony and the opening ceremony of the Rio de Janeiro Olympics in 2016, not to mention the 2022 Super Bowl half-time show. Earlier this month, she hit the headlines for her work on the sets for U2’s residency in the new $2.3 billion Sphere arena in Las Vegas. But her great love is theatre.

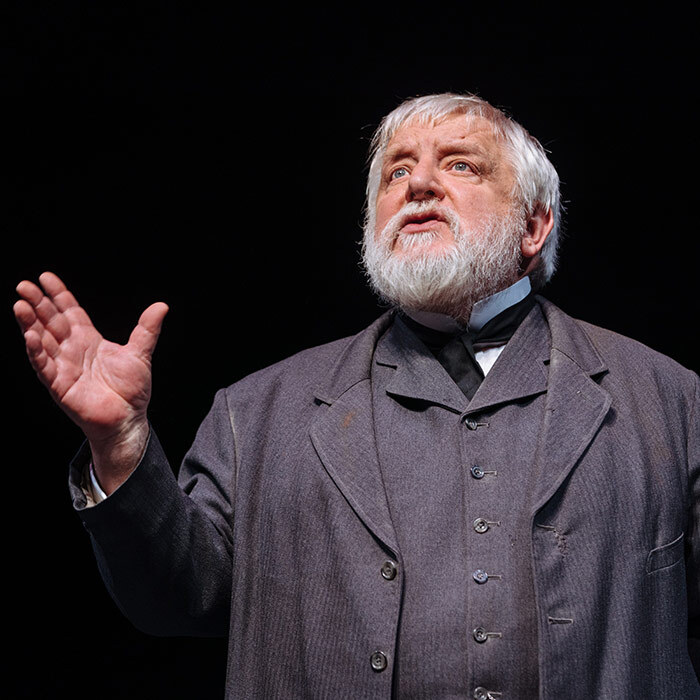

This year, four National Theatre shows, all of which transferred to the West End, have featured her sets: Dear England, The Lehman Trilogy, The Motive and the Cue and The Crucible. Her impressive theatrical back catalogue includes some of the biggest shows of recent years, from Lyndsey Turner’s Hamlet at the Barbican, starring Benedict Cumberbatch, to Lucy Kirkwood’s Chimerica, for which she won an Olivier award.

‘What would be the point of sustaining life if that life didn’t include ritual and art?’

Devlin, now 52, has, in fact, won three Oliviers, as well as a Tony and an Emmy. She was also made a CBE in 2022. Today, she’s dressed casually in black, her hair fixed in a bun with a pencil. “You’re getting a very early-morning version of me,” she admits. “But I was in Manchester last night, opening Danny Boyle’s new show Free Your Mind.” A blend of dance, theatre and pure spectacle, the epic large-scale show – which opened Manchester’s £242 million Aviva Studios – feels textbook Devlin.

Her work happily moves between high culture and pop culture. And she loathes the word ‘client’: “I had never heard the word ‘client’ until someone paid me, which wasn’t until 20 years into my practice. There is no client in theatre. I’m also trying to forbid the word ‘production’, and I can’t bear the juxtaposition of ‘entertainment’ and ‘industry’ because, to me, it devalues the word ‘entertainment’, which comes from the French ‘inter’ (among) and ‘tenir’ (to hold together).”

She is the woman countless artists, from pop stars to theatre directors, call on to fulfil their vision. But, more recently, she has been making her own artworks, such as 2016’s Mirror Maze – the scent-infused installation in Peckham created with Chanel. She is finally happy to call herself an artist, but this has brought her back to the collaborative nature of theatre with a renewed passion.

“I’m on a bit of a mission. There’s a group of theatre designers – including Bunny Christie, Miriam Buether, Tom Scutt, Lizzie Clachan – who are part of a similar movement in stage design, where we consider what we make to be a work of art, as well as a work of applied art.”

Still, it’s taken nearly 30 years to get her name on the poster, she jokes. “I’m like: ‘Come on, let’s get our fucking names on the buses.’ Because actually, the visual world that tells the story, and the relationship between director, designer, writer and the work itself, is the crucible where the work is made. What’s beautiful about Free Your Mind is the poster just has [the creative team] in alphabetical order.”

Q&A

What was your first non-theatre job?

A wages clerk.

What was your first professional theatre job?

Edward II at the Bolton Octogon in 1996.

Who or what was your biggest influence?

Rose Finn-Kelcey, may she rest in peace. Steam Installation was the biggest influence on my practice. Lucio Fontana was another big influence.

What’s your best advice for auditions?

There has to be this meeting point of things for a person to work with us: a really insatiable curiosity, a hunger for work, a love of theatre and live interaction and the community of an audience. You need conviction.

If you hadn’t been a designer, what would you have been?

I’d be lost. It’s hard to imagine another garment that would have fitted me as well as theatre. I don’t know that I would have thrived anywhere else.

Do you have any theatrical superstitions or rituals?

Every morning I observe and photograph the line of light that comes either side of my blinds. I set my alarm 20 minutes before I have to get up. It’s my buffer time when I don’t have to engage with the mechanics of the day, but only with that line of light. It’s a little isolated contact with our nearest star, from which we get all our energy.

What is your next job?

There are some revivals and three West End shows on now, I’ve got a project with Lyndsey Turner next year and a piece at the Met Opera. I’ll be at Art Basel as well, building on the work that I did with Lyndsey on The Crucible.

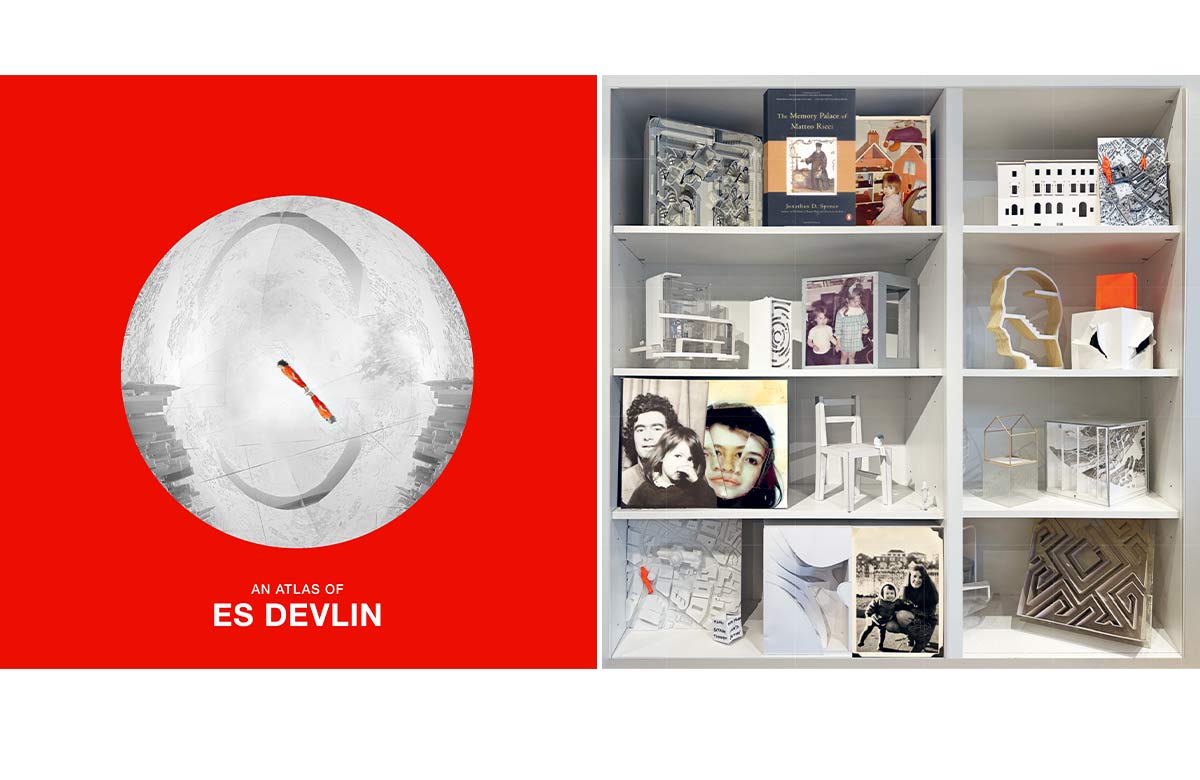

The politics of design

Part of the problem, of course, is that a theatre designer’s work is transitory. When a play is over, it exists as what she calls “skeletal traces” in the mind of the audience. But now, fans can pour over her extraordinary designs in a new book, An Atlas of Es Devlin, featuring nearly 900 pages of sketches, fold-outs, cut-outs and photographs. The book accompanies an exhibition of her work, which will open at New York’s Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum this month. The exquisitely designed monograph features essays about her work and interviews with figures including Cumberbatch, Turner, Brian Eno and Sam Mendes. It also includes witty, personal texts for each project. We find out that she brought her own furniture from home to augment the set of Hamlet, and that the Olympic closing ceremony was nearly a disaster when a panel from Damien Hirst’s Union Jack spin painting went missing.

In many ways, the book is a love letter to theatre and our shared past of watching live performance. “I really wanted that to be the case,” she says. “Donatien Grau [adviser for contemporary programmes at the Louvre] writes in the book: ‘Es Devlin includes everybody in her work.’ And I think I do. There’s a sense that we have all been through this 30-year period together but haven’t really had a moment [together]. I keep thinking of that line from The Motive and the Cue where John Gielgud says: ‘It didn’t feel like a body of work we were making, it just felt like we were tumbling from one thing to the next, while Joan Littlewood was frying bacon in the wings.’ ”

‘We need art the way we need sleep, imagination, love and shelter. It’s a birthright’

She believes passionately that the arts have been devalued in an industrial society. “Last night at the opening of Aviva Studios, when we had the culture secretary speaking about the value of the arts, it was about putting a fucking pound sign on it. They said: ‘The arts make X number of billion pounds for our economy.’ That’s not the point. The whole point about ritual and art is we need it the way we need sleep, the way we need imagination, love and shelter. It’s a birthright. What would be the point of sustaining life if the type of life that we sustained didn’t include ritual and art?”

She believes that set designers, especially female set-designers, are rebelling against these market values. “I really noticed that in this beautiful movement during the pandemic called Scene Change, led by Soutra Gilmour, Katrina Lindsey and others. I feel a real affinity with all of these women. My project in set design is to forge a path for all of us to be recognised. I feel that hierarchies were one of the reasons I was relieved to get away from theatre when I did. And I still find it a bit oppressive now, if I’m honest, that those hierarchical systems still apply.”

Devlin thinks many of our problems stem back to an education system in which a tier of men are educated “not to be aware of anything other than their experience”. She adds: “Think of that amazing play Posh about the Bullingdon Club, and David Cameron and Boris Johnson – there’s a degree of that in the way the British theatre system has historically been run, with boys who went to Cambridge making great work at Cambridge with writers from Cambridge.”

She is also “chiseling away” at other theatre orthodoxies. “As a woman with kids, do I need to be in the theatre all day, all night, every day? Or can I go in and out? I’ve hopefully made some inroads on the definition of what commitment means. If I commit my 30-year build-up of visual language, and I have a great associate who’s in the room dealing with the details of ‘is this the right prop?’, that is as committed as actually being there from 10am to 10pm every day of the tech and missing my son’s football match or not being there when my daughter needs to talk to me.”

She points out that, broadly, set design has been “a female or non-binary thing, like interior design”. Can that make it seem low-status? “Well, even last night, it was definitely the Danny Boyle show. He’s a massive name and the production has to sell tickets. I adore him, he’s a friend. But we did a round of press, and I was definitely an add-on among the men.”

This is curious, as she brings so many art forms together. “I do think the quality or the aesthetic of live music has changed since I’ve been working in it,” she says simply. “Interestingly, at the moment, the beautiful Madonna show and Dear England have the same sets. But I didn’t design the Madonna show. It’s designed by my dear friend and colleague Ric Lipson, who had not seen my Dear England set. But we work together, and these are forms we have been collaborating on [in our work] with Beyoncé.”

It all stems back to an artwork that Devlin saw in 1992. “I went to see Rose Finn-Kelcey’s Steam Installation at the Chisenhale Gallery. It consisted of two metal planes, almost like an extractor fan hood on a cooker, and there was this haze suspended between the planes. The Dear England set, The Crucible set and loads of my pop sets wouldn’t have happened if I hadn’t experienced that. And I’d like to think that Madonna’s set wouldn’t have happened if little old me hadn’t wandered into that. And equally, some of the things I have made wouldn’t have happened if other designers hadn’t walked into those spaces.”

How it all began

Devlin grew up in the small Sussex town of Rye with a teacher mother and journalist father. She and her siblings entertained themselves by making things and putting on shows using torches and cardboard cut-outs. She learned three instruments and every Saturday went to London for classes at the Royal Academy of Music, but realised she was not talented enough to turn professional. She did an English literature degree, then took an art foundation at Central Saint Martins and had a three-year place lined up to study photography, print-making and book-making. But then a tutor suggested she apply for the now-defunct Motley Theatre Design course, a one-year programme founded in 1966 that counts some of British theatre’s best-known designers among its alumni.

After graduating in 1995, she won the Linbury Prize for Stage Design and with it, her first professional commission: Edward II at the Octagon Theatre in Bolton. She spent the mid-1990s designing plays for London’s Bush Theatre and received her first big break designing the set for Harold Pinter’s Betrayal at the NT in 1998 – inspired by artist Rachel Whiteread’s public sculpture House. In the book, Devlin tells a funny story about Pinter introducing her waspishly as: “This Es, she wrote the play”, because she was showing interest in more than just the scenery.

Today, her team of eight designers at Es Devlin Studio are largely trained in architecture. “Broadly, the skills required to work in the studio are not skills taught in theatre. Young theatre designers often don’t want to join a studio, they want to go off to be theatre designers and work their way up. So we tend to attract refugees from architecture who are tired of designing banisters for buildings that never get built.”

‘My team can’t design for theatre if they haven’t listened to Rupert Goold directing or observed how Lyndsey Turner drives a tech’

Her team work on projects for Chanel and U2, of course, “but I say to them: ‘You can’t really enter into the other spaces that we work on if you haven’t done theatre, because when you work on the museum work, the artwork, the fashion, the music, you need to bring what makes my work valuable in that space. And you won’t bring it if you haven’t sat and listened to Rupert Goold directing and observed how Lyndsey Turner drives a tech.’ ” The Motley course (which closed in 2010) is being rebooted as of this year, under the new title of the Genesis Theatre Design Programme, with Devlin on the board.

“It’s only taking global-majority or low-income students. It’s a really exciting turn of events in stage design, because the sector needs to invite more people in,” she says. She’s just taken the first intake of students to see her most recent design for Canadian singer The Weeknd and introduced them to the crew.

Access is everything, Devlin says. That is why Dear England, James Graham’s play about Gareth Southgate’s England football team, is very close to her heart. “That piece has been so important in terms of my belief in what theatre can do for society.” She loves that you get people who love sport and people who love theatre in the same room. “At the beginning, you could see people just thinking: ‘Well, I’ve got nothing in common with this other person on my row.’ But by the end, everybody’s crying and singing along to Sweet Caroline.”

Evolving her practice

Devlin lives in a Victorian house with a modernist extension, five minutes’ cycle from her Peckham studio, with her husband Jack Galloway, a costume designer, and their two teenage children. Since 2017, she and Galloway have shared the ground floor with her team of designers. But now, the team is moving out. “My studio will leave my house and I will spend the day in a white empty room, making I have no idea what, and it might be rubbish. I’ve got a fantasy at the moment about painting TV sets,” she says with a gleam. “I’ll still be at the core of projects, but I want to let my team blossom and run with the work.”

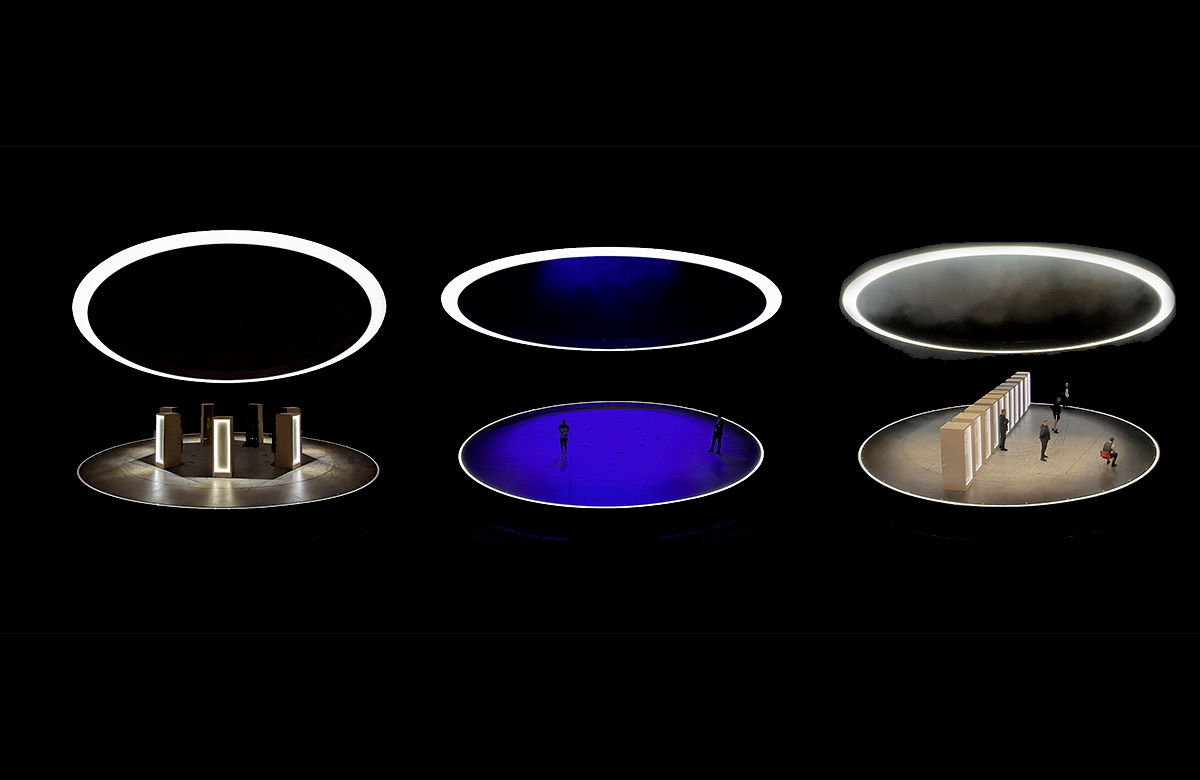

Despite her success, she says she is driven by a fear of failure. “I think anyone who engages with such care and love as we set designers do feels that humiliation because you want it to be as you saw it in your mind. And it never is.” She tells a story of working with Turner on Chimerica: “We sat there after press night, had a drink and redesigned the whole thing. We said: ‘We should have done two revolving cubes. It should be one for China, one for America.’ ” The same thing happened on The Lehman Trilogy. The set started out as a clear, static box. But then she and director Mendes realised that placing it on a revolve would stop the storytelling from getting stuck. “It helps churn you through those years and those beats,” she says.

In fact, she thinks it is amazing she hasn’t made more mistakes. “Part of the reason I’m wanting to retreat into my room is I just feel my nine lives have been used up. The only reason that those complete disasters don’t happen is because you devote a complete force of character. And it does fucking exhaust you.”

I tell her many people are just grateful that she’s still doing theatre. “Honestly, this year, with four bits of theatre, I’m desperately trying to make the money back,” she laughs. “But the quality of exchange – intellectual, visceral, the exchange of ideas and of love – is ultimately unmatched in any other genre. And it’s fair to say I have tried quite a lot of other genres.”

CV Es Devlin

Born: Kingston upon Thames, 1971

Training: BA (hons) English literature, University of Bristol; fine art, Central Saint Martins, Motley Stage Design

Landmark productions:

• Wire – Flag: Burning, Barbican, London (2003)

• Macbeth, Theater an der Wien, Vienna (2003)

• Chimerica, the Almeida and Harold Pinter Theatre, London (2013)

• The Nether, Royal Court, London and Duke of York’s Theatre, London (2015)

• Carmen, Bregenz Festival, Austria (2017)

• The Lehman Trilogy, National Theatre, Gillian Lynne Theatre, London and Broadway (2018-23)

• Dear England, National Theatre and Prince Edward Theatre (2023)

Awards:

• Linbury Prize (1996)

• TMA for Howard the Rookie (1998)

• Olivier for best costume design for The Dog in the Manger (2006)

• TPi Set Designer of the Year (2010, 2011 and 2012)

• Olivier for Chimerica (2014)

• Olivier for The Nether (2015)

• London Design Medal (2017)

• D&AD President’s Award (2019)

• Ivor Novello award for best contemporary song for Children of the Internet (2021)

• Tony for The Lehman Trilogy (2022)

• Emmy for the Super Bowl half-time show (2022)

An Atlas of Es Devlin, published by Thames & Hudson, is out now, and the accompanying exhibition is at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian, in New York from November 18-August 11, 2024

Big Interviews

Alistair Spalding and Britannia Morton

Joe Robertson and Joe Murphy

Sutton Foster

Julian Bird

Recommended for you

Opinion

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99