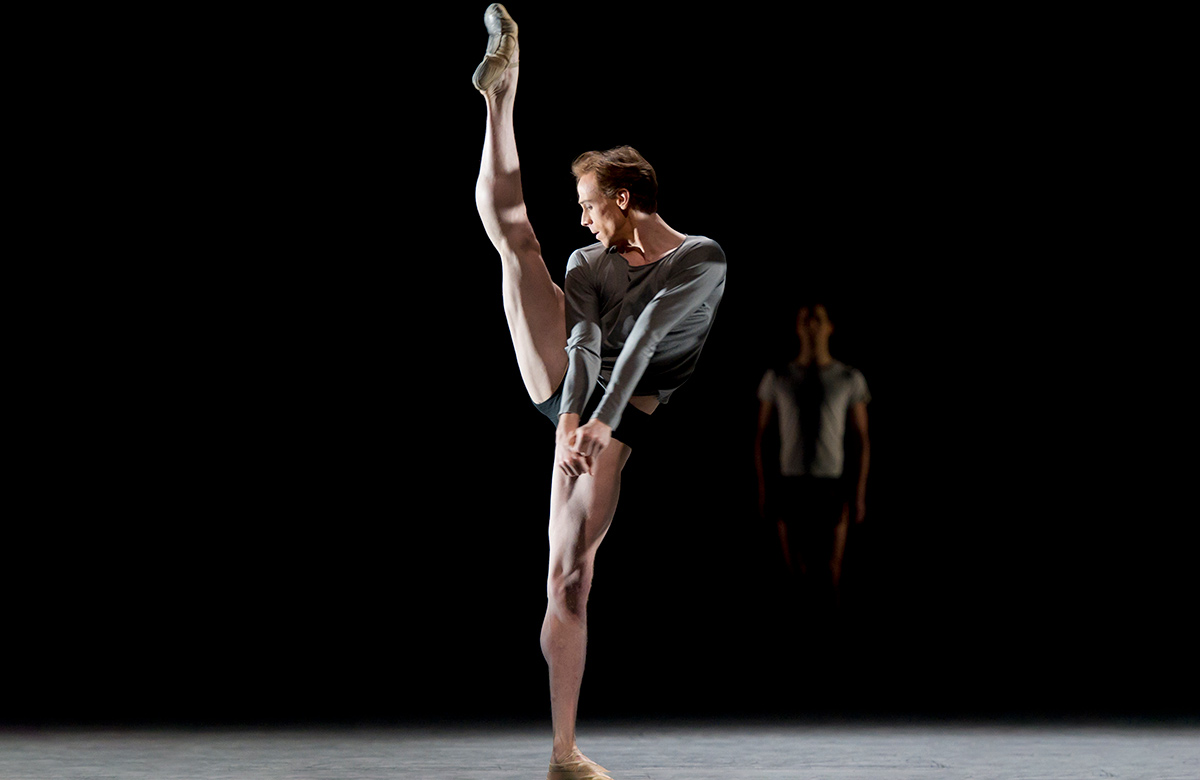

Edward Watson

Georgia Snow

Georgia SnowGeorgia is features editor at The Stage, having joined the company in 2014.

After almost three decades at the Royal Ballet, Edward Watson has retired from performing – but he is continuing with the company as a coach. The acclaimed former principal dancer tells Georgia Snow about his working bond with Wayne McGregor, swapping the barre for spinning classes, feeling misunderstood by the establishment and the ‘big turnaround’ moment in his career

If Edward Watson had any designs on slowing down during his retirement, they didn’t last long. Last October, he hung up his ballet shoes after an acclaimed 28-year career. Watson gave his final performance at the Royal Opera House in Wayne McGregor’s The Dante Project on a Saturday night. On the Monday, he was back in Covent Garden for his first day as a coach with the Royal Ballet, where he now works with dancers and choreographers in the rehearsal studio.

“Retirement is busy, that’s for sure,” he tells me when we meet at the Opera House four months into his new life as a coach. Watson was doing “double duty” as a dancer and coach towards the end of his tenure as one of his generation’s most celebrated principals, but now is relishing the opportunity to throw himself into the new role fully.

“I’m still working out all the different sides to it, it’s a lot to take in,” he says. He has already worked with casts on Romeo and Juliet, The Nutcracker and Swan Lake, “basically making them the best they can be with the knowledge I have”.

Watson’s official title is répétiteur to the principal dancers, meaning he will rehearse the company’s principals in whatever they are working on. If they are taking on an existing role, it is almost certainly one he has danced himself – his long list of credits include almost all classic ballets in the repertoire – while more roles have been created for him to perform than any other dancer currently at the Royal Ballet.

“I’ve created a lot of roles and not just the principal ones. I was in the Royal Ballet for 10 years before I was a principal, so I did all those corps de ballet roles, soloist roles and the principal roles. It’s helpful that I don’t just know the top-end stuff, I know how the top-end roles fit into the rest of the ballet, and obviously I have worked with lots of different choreographers, so that helps too,” he says.

Creating new work

At the moment, he is assisting the US choreographer Kyle Abraham on his “brilliant new ballet” The Weathering, which premieres this week as part of a triple bill alongside revival pieces by Christopher Wheeldon and Crystal Pite. Watson’s fingerprints will also be on Wheeldon’s new full-length work Like Water for Chocolate, which opens in June.

The Weathering is Abraham’s second piece for the Royal Ballet and Watson also worked on his first, Optional Family, last year. “Ed has a no-holds-barred approach in the studio that is very direct with a laser focus,” Abraham says. “He’s able to take his job with the utmost seriousness and still make space for moments of levity in the room.” A reflection of the hundreds of rehearsal-room days Watson has experienced perhaps, and an indication of the insight he brings to the creation of new work. “It’s nice to know that I haven’t shut that side of myself off,” he says. “I’m still good at being creative.”

Watson works full-time on the Royal Ballet’s coaching team, travelling into the Opera House every day for work, as he has done for the past 28 years, and spending most of his time in a studio. But despite any outward similarity, he says, his entire mindset has changed.

“The concentration is really different because the focus isn’t about you. It’s straight on the person in front of you and how you can get the best out of them. You’re watching them, what they’re doing wrong and thinking: ‘How am I going to tell them that without putting them off or ruining their confidence?’ It’s such a different kind of focus. When you do a job like that for so long, you know how to wind yourself up and slow yourself down, how to get the best out of yourself, and it’s not that. It’s something else entirely.”

While it sounds as if Watson must have been a shoo-in for a role like this, the pressure and anxiety of what a dancer in his position would ‘do next’ still loomed large. “You do feel that. You hit 40, or even before, and realise that this isn’t forever. You grow up knowing it’s not forever, but when you’re in the middle of it, it takes so much focus to actually do it, you don’t have the brain space to think about anything else. But it does creep in. In those bigger gaps between performances, you have a bit more space and time to think about it,” he says.

Those small voices grew louder until the decision was made, but he insists there wasn’t a “big moment” when he knew the game was up.

“Though I did sometimes look around the room at 19-year-olds who weren’t even born when I joined the company and I’m probably older than their dads, and I’m on stage in the same outfits as them, and I thought: ‘Maybe that’s a sign to have a rethink’,” he laughs.

Watson spent 17 years as a Royal Ballet principal, and more than a decade before that dancing with the company, so transitioning out of a routine he has spent more than half his life doing was “weird” to say the least. For his entire adult life, Watson’s schedule ran to the same cadence, punctuated every day with morning ballet class, a ritual and a constant of any ballet dancer’s life (even during lockdown, the company met online at 10.30am every day for class, Watson using a kitchen chair as his barre).

“When I stopped, I needed to give my body a rest and I didn’t want to just keep doing ballet class every day and not do anything with it, but I realised I missed the therapy of it. The physical therapy of getting rid of all your crap. You do it in class every day to music and you sweat and get rid of it all. Whatever I was feeling, happy or angry, I could just pour it into the movement, which was what I always did in roles,” he says.

It took him a couple of months to realise that something was missing. “I felt a bit stuck. I didn’t know what it was.” So how does he get that release now? “Oh, now I do spin classes,” he quips. “Sweating to music, I get it all out there. That’s my therapy now. I realised I needed that outlet.” Though he adds quickly that he is “not saying that I’m never going to dance again. Never say never”.

Watson’s journey to retirement was also complicated by a terrible foot injury in his early 40s, which kept him off stage for a year and delayed several landmark performances at which he could have bowed out. Then Covid came along and knocked things on even further.

Having promised McGregor he would do his Divine Comedy-inspired ballet The Dante Project – “I have never been able to say no to Wayne” – the London premiere of the project was postponed three times during the pandemic. “I had to just keep pushing. It’s probably the proudest I’ve ever been of myself that I actually just completed it, against the odds. I was 42 when we started making it and I was 45 by the time we did it. A lot happened and that’s all there in the piece, so I’m glad I hung on.”

Evidently, so was everyone else. Watson’s performance in the piece was universally celebrated and has since earned him an Olivier nomination for outstanding achievement in dance. Already the proud owner of one Olivier (having won the same award in 2012 for Arthur Pita’s The Metamorphosis), he says he is “really grateful” for little moments of recognition whenever they come. “This one’s 10 years after the last one, it’s kind of ridiculous, I feel like a right grandma.”

The Dante Project was the most recent in a string of collaborations between Watson and McGregor that stretches back 20 years and comprises a dozen pieces including the Virginia Woolf-inspired triptych Woolf Works and 2012’s Carbon Life. He calls McGregor, the Royal Ballet’s resident choreographer since 2006, an “absolute genius”, and the opportunity to create roles in his works as “my stroke of luck”.

“Someone so prolific, so aware of everything that’s going on in the world – to be part of that creative juggernaut that he brings in, what an absolute dream,” he says.

What draws them to each other time and again? “You’ll have to ask Wayne. Obviously I was drawn to him but it’s always the choreographer’s decision who they work with, and that can change. I guess I sparked an interest and I was open and always said yes to everything. I never arrived with a set of restrictions, I arrived with a whole load of positivity. He made you feel like you could try anything.”

The pair first worked together in 1999 on Symbiont(s), which Watson considers to be one of the breakthrough moments in his career. It was the first time, he says, people saw him dance and thought: “Maybe there is something there.”

His fearless, striking style was a perfect match for McGregor’s pioneering choreography, and their first piece together in the Royal Opera House’s small Clore Studio quickly led to Watson being cast in several other big roles. Further collaborations with McGregor also followed – including the 2003 pas-de-deux Qualia with Watson’s several-times partner Leanne Benjamin – and by the time McGregor made the electrifying, groundbreaking Chroma in 2006, starring Watson, the duo were established names.

Q&A

What was your first non-theatre job?

Never had one, this is it. I worked in a coat check for my friend once at a big office party in a tent somewhere and gave out their cloakroom tickets. Everyone lost their tickets.

What was your first professional theatre job?

This. I joined the Royal Ballet at 18 [Watson’s first appearance was in Sleeping Beauty].

Do you have any advice for young dancers trying out for a company?

Listen to your teachers, allow yourself to be shaped and guided, don’t think you know it all. Even though it takes a certain amount of confidence to put yourself out there, it doesn’t mean that you know everything.

Who or what was your biggest influence?

I’d say my brothers and sister, it’s amazing how resilient and great parents they are. In a professional sense, the choreographers I’ve worked with – Wayne McGregor, Christopher Wheeldon and Arthur Pita.

What do you wish someone had told you when you were starting out?

You want someone to say it’s all going to be all right, even when you have those moments when you feel misunderstood or like you’re never going to get there. I wish I’d had someone to say: ‘It’s going to be fine. You can do it.’ I went into my whole career with this huge amount of doubt surrounding me.

If you hadn’t been a dancer, what would you have been?

Definitely not a coat-checker. Probably something else creative I guess, that’s where my natural brain is.

Do you have any theatrical superstitions or rituals?

I don’t really, I believe every day is different. I wouldn’t walk under a ladder, but I’m not particularly superstitious, though I always brushed my teeth before I went on, that was the last thing I did.

Dance at an early age

Born in Bromley and brought up in Kent, Watson, who has two brothers and a twin sister, grew up with a dance school opposite the family home. He and his sister began taking lessons as young children.

“We were always dancing around to music on the TV, the two of us throwing each other around, and my mum just wanted us to channel that into something,” he says. Once a week turned to twice a week and it was during a ballet exam aged nine or 10, Watson recalls, that the examiner suggested putting him forward for the Royal Ballet School. A weekly programme at the coveted school in Richmond Park, west London, followed and Watson joined full-time at 11. Thrown into daily ballet classes and boarding-school life was “such a shock”, he remembers. “My head spun for a couple of years.”

They would take the coach into central London to watch the company’s ballets and sit in on dress rehearsals, deliberate over their favourite dancers and try to say hello. “I didn’t know any dancers before, so it was exciting and sparked my inspiration, the possibility of what lay ahead,” says Watson. “It seemed so far away and then all of a sudden you’re in the middle of it all.”

He left the school at 18 and immediately joined the Royal Ballet company, thrown into a whirlwind of ballets to learn and talent to prove. Though his ascent through the ranks didn’t always resemble a fairytale.

He says he has “always been terrified” and was, both then and now, “a really nervous performer – it took a lot to get me on stage”. He acknowledges that those first few years of his career in the Royal Ballet’s corps de ballet “wasn’t the happiest time”.

“You’re there to be in the bigger group numbers and you have to be the same as everybody else,” he says, something he found challenging. “I was so nervous and overwhelmed. My big panic was that I would forget my steps, which I did, constantly. I was wrong all the time and that was brought up a lot.”

He has also felt misunderstood at times within the company – his career has spanned four directors of the Royal Ballet, including the current incumbent Kevin O’Hare – and says he felt the weight of the establishment bearing down on him during those early years. “It took a while for people to understand me, and then when they do it’s good.

“While I was in the middle of it, I felt like: ‘Nobody understands me, I feel I don’t belong here, I’m weird,’ and then before I knew it I’d been here 27 years, so I think they must have understood me.”

A turning point came in 2007 when Watson danced his debut as the doomed prince in Kenneth MacMillan’s Mayerling. The rapturous reception of his performance felt like “a huge moment”.

“That was a big turnaround in terms of what I thought I was capable of and shutting a few people up and surprising people as well. They thought: ‘He won’t be able to do that’ or they never saw my kind of build in that role, and it was one of the biggest successes I’ve ever had,” he says.

Does he think he would come up against those questions – about his physicality, his individuality – if he were starting out today? “I think that question about male dancers has grown with what it means to be a man and what it means to be a woman. You don’t have to stand behind the woman and look tough. They say: ‘Don’t dance like a woman’ – well, women are so many different things, which part of it don’t you want me to be?

“When you’re dancing, you’re expressing emotions through movement. If that describes who I am as a man then fine, whatever. Judge me. I’m going to be judged anyway. Every step is being judged – what I look like, how I feel about something.”

He speaks with a shrewd composure that comes from years of being asked: “What was it that was different about you? Why did you do this, why didn’t you do that?”

He continues: “It’s all dancing. That’s what I want to say to a lot of people, it’s just dancing. It’s humans telling stories of love, loss and anger. Everybody, whatever gender, race, sex, has those things and why shouldn’t they be allowed to express them? You just want to be completely authentic to who you are and how you feel. That’s what I’m trying to do as a coach – allow people to be themselves completely authentically but within the rules of what’s right and wrong in terms of whatever ballet they’re doing.”

Attitudes towards who is allowed to make and perform ballet are changing, he agrees, as are ideas of gender in what has traditionally been an overtly gendered art form. How much these shifts trickle down to the rigour of classical ballet training however is debatable, Watson thinks – “it is a really rigid system and it has to be, that’s the brilliance and the skill of it” – yet he does believe younger dancers are more able to see “the possibilities of what you can do with that training”.

He is too coy to say he has played a part in that or has been a driver for progress, adding that he “never set out to change anything”, but hopes he has at least “given other younger male dancers the possibility to be themselves and do it their way… It’s not about breaking the rules, it’s about making some new ones, within what’s right and wrong”.

CV Edward Watson

Born: 1976, Bromley

Training: Royal Ballet School

Landmark productions:

(all with the Royal Ballet)

• Symbiont(s) (1999)

• My Brother, My Sisters (2005)

• Chroma (2006)

• Mayerling (2007)

• The Metamorphosis (2011)

• The Winter’s Tale (2014)

• Woolf Works (2015)

• Song of the Earth (2015)

• The Dante Project (2021)

Awards:

• Critics’ Circle National Dance award for outstanding young male artist (2001)

• Critics’ Circle award for best male dancer (2008)

• Olivier award for outstanding achievement in dance for The Metamorphosis, Royal Ballet (2012)

• MBE for services to dance (2015)

• Prix Benois de la Danse for The Winter’s Tale, Royal Ballet (2015)

The Weathering by Kyle Abraham runs as part of a triple bill at the Royal Opera House until April 7. For more: roh.org.uk

Big Interviews

Recommended for you

Opinion

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99