Natasha Tripney

Natasha TripneyNatasha is international editor for The Stage. She co-founded Exeunt magazine and regularly writes for the Guardian and the BBC.

Melly Still has worked in theatre, dance and opera – directing, writing and designing – for 30 years. As she stages a production about the climate emergancy, she tells Natasha Tripney about the importance of pushing boundaries in children’s theatre, her love of big stages such as the Olivier, and her journey in defining her job title, as someone with many accomplished strings to her bow

Music drifts across the grounds of the Master Shipwright’s House in Deptford. Outside the historic building, one of the few remaining parts of Deptford’s royal dockyard, now an arts space, a group of performers are just wrapping up a rehearsal of The Gretchen Question, with the Thames at their back and the buildings of London’s Docklands glinting across the river.

This new, multi-stranded collaborative piece exploring climate change and colonialism has been co-created by Melly Still and Max Barton. Over the years, Still’s work has encompassed theatre, opera and dance – directing, writing and designing. She has also directed on many of the UK’s biggest stages – including the National Theatre’s Olivier and at Glyndebourne – but this is her first time working outdoors, contending with the wind, the weather and the autumnal chill.

The Gretchen Question is, she says, a sonically intricate piece that uses radios to create a sense of melting between worlds and times. The idea for the show goes back to 2015, “when the word ‘Anthropocene’ was just beginning to be part of our vocabulary”, she says. Around that time, scientists announced that a new geological epoch, the Anthropocene, should be declared because of the profound impact of humans on the earth.

Together with a group of previous collaborators, musicians and friends, Still set up a “sort of laboratory to discuss what we felt about the idea of climate change”. They spoke to climate scientists at King’s College London and came to realise that what they were feeling was akin to grief. The show they wanted to make would, she hoped, articulate grief for the things we were on the verge of losing. Ice was central to this. Still describes the resulting production as “a farewell letter to ice”.

Initially, she thought the finished project might be staged at London’s Somerset House, where producer Fuel Theatre is based. It is a place which, fittingly, given the nature of the piece the team hoped to make, symbolised “dominance in the age of enlightenment”. That impulse to voyage around the world, she explains, “claiming and naming, wanting to have complete dominion, has an impact on where we are today”. Without explicitly making a piece about colonial power or patriarchy, they wanted to examine and problematise those ideas.

When Still was eventually able to revisit the project after lockdown, she joined forces with Barton, the theatremaker, musician and co-founder of Second Body, with whom she had worked in the past. Still was familiar with the Master Shipwright’s House, which now houses the new Shipwright theatre, having been to parties in the building now owned by Willi Richards and Chris Mažeika, who bought and restored it in the 1990s. The building itself dates back to the early 1700s and is at the heart of the former royal dockyard, which was founded by Henry VIII.

It struck her as, in many ways, a perfect setting for the piece. Like Somerset House, it is entwined with history. “They built ships here. There were huge political gatherings in these rooms, big global decisions being made.” It’s impossible not to get a sense of that, as we sit in one of those once-grand rooms, the sun setting outside the vast sash windows. “You can’t help but feel the history of the place and the ghosts of those people. There’s an umbilical cord that goes right back to them.”

The Gretchen Question was co-commissioned by We Are Lewisham and is part of the London Borough of Culture 2022 programme. With its allusions to The Little Match Girl and Faust – the title derives from Goethe and refers to the kind of uncomfortable question that is difficult to ask and even more difficult to answer – its time-hopping narrative moves from 18th-century polar expeditions to the present. It is not an easy work to slot into any one box, but this is in keeping with Still’s approach to her career and her life.

The art-versus-theatre question

She was born in 1962 in Cambridge, and has written about how her parents instilled a love of storytelling in her when she was young: “My first teachers were my parents,” she once wrote. At her local comprehensive, she was fortunate to encounter a PE teacher who had an interest in the work of Rudolf Laban. This meant that, from the age of about 11, she was exposed to ideas from post-modernist dance, ideas about the beauty of the moving body, and “suddenly, the world started to make sense”.

In sixth form, she encountered another inspiring teacher, this time in art class. “It’s always the teachers,” she reflects. Still developed a strong interest in dance, art and drama, and though her teacher tried to steer her towards art school, she couldn’t decide which path to pursue – she just didn’t want to choose. There was only one place in the whole of the UK that offered a combined degree in drama, dance and art – York St John – so Still studied there, on a four-year course, which gave her time to immerse herself in the work of Pina Bausch and other modernists.

After finishing college in the 1980s, one of her first jobs was as the assistant choreographer of a production of James and the Giant Peach at York Theatre Royal. “It was the most terrifying thing, learning all these wild steps and high kicks.” She remembers thinking: “This isn’t for me. I feel so alienated.” While working on the production, she met Tim Supple, who would go on to be artistic director of the Young Vic. “We went to the pub, and I remember thinking I’d landed with someone with the same ideas, and it was just so exciting.” They became close and gradually Still became aware that there was this other world of professional theatre open to her. “A world where you didn’t get paid so you had to get paid jobs in order to do your own work. And then, gradually, those two worlds merge.”

During the early part of her career, she worked on a series of productions, often with Supple, as a deviser, designer, writer and co-director, including working on Grimm Tales at the Young Vic and Tales from Ovid at the Royal Shakespeare Company. “I didn’t ever land on being one thing or another,” says Still, but over time she started to devise and direct more, which made her realise that “this is what I love more than anything”.

Q&A

What was your first non-theatre job?

I worked as a painter, decorator and scenic painter.

What was your first professional theatre job?

Assistant to the choreographer of James and the Giant Peach in 1985, followed by choreographer for Oliver! and Our Day Out – both for York Theatre Royal in collaboration with the incredible Youth Theatre Yorkshire. I was way out of my depth. Apart from the anarchic joy of working with kids, I felt I’d landed on another planet.

Who or what was your biggest influence?

Back in the 1980s? Pina Bausch, Tim Supple, Robert Wilson, Simone de Beauvoir, and artist Belinda Gilbert Scott. And Talking Heads.

If you hadn’t been a theatremaker, what would you have been?

Maybe a painter. I did try it – between theatre jobs – until the mid-1990s, but I found myself longing to be surrounded by people. I couldn’t cope with isolation and wondering what the point of me was. And, really, I wasn’t skilled enough.

Do you have any theatrical superstitions or rituals?

Not really. Although I don’t think I’ve ever gone into a rehearsal without first going for a run or doing yoga. But I’m definitely not superstitious – I can’t imagine avoiding saying ‘Macbeth’ before a performance.

The children’s-theatre question

In her 40s, she began to reposition herself. In 2003, she directed Beasts and Beauties, based on the book by Carol Ann Duffy, for Bristol Old Vic, which she followed with a production of Alice in Wonderland for the same venue.

It was her 2005 production of Coram Boy, based on Helen Edmundson’s adaptation of Jamila Gavin’s Whitbread award-winning young-adult novel, which really made a splash. Staged in the National Theatre’s Olivier, the lavish production, coming on the heels of the NT’s production of His Dark Materials, proved to be a big hit for the theatre. Still both directed and co-designed Coram Boy, which featured a 16-member onstage choir and a seven-piece chamber orchestra. The production fused the music of Handel with a story about an abandoned child who ends up in Thomas Coram’s Foundling Hospital in London. It mixed choral music with a narrative that did not shy away from the brutal fate that awaited unwanted children of the time. It was well-received and returned to the National for a second run in 2006 before transferring to Broadway in 2007. “This huge production may stint on traditional scenery, but it is stuffed to the rafters with just about everything else,” wrote Charles Isherwood in the New York Times. It was nominated for four Oliviers and six Tony awards.

Though the National decided to place an age restriction on the show for under-12s because of its dark and often distressing subject mater, it was, like much of Still’s work at the time, intended for audiences of all ages. “I am very interested in theatre that traverses the generations,” she says. She had young children herself and was interested in the things that fired their imaginations and their reactions to the stories they were reading. “That became a massive influence,” she says. There is still often a relatively narrow idea of what family theatre or children’s theatre can be, she adds, which was something she was keen to resist.

Today, she says, there are a lot of conversations “about what wouldn’t be appropriate for children or a family show”. But this is a way of thinking that doesn’t excite her. While there are some concepts that are beyond a child’s comprehension, “we make the mistake of thinking children need to be protected”. Actually, she says, “children have a lot of complicated and difficult thoughts and often those stories that don’t shy away from brutality can help them channel some of those feelings and legitimise them.”

Still followed Coram Boy with a stage version of Richard Adams’ Watership Down, a book responsible for many a childhood nightmare, and a production of Cinderella at the Lyric Hammersmith that retained the scene from the original Grimm version in which the stepsisters cut off their toes in an attempt to make the glass slipper fit, before having their eyes gouged out by doves (which made the rain of paper birds at the very end both magical and sinister).

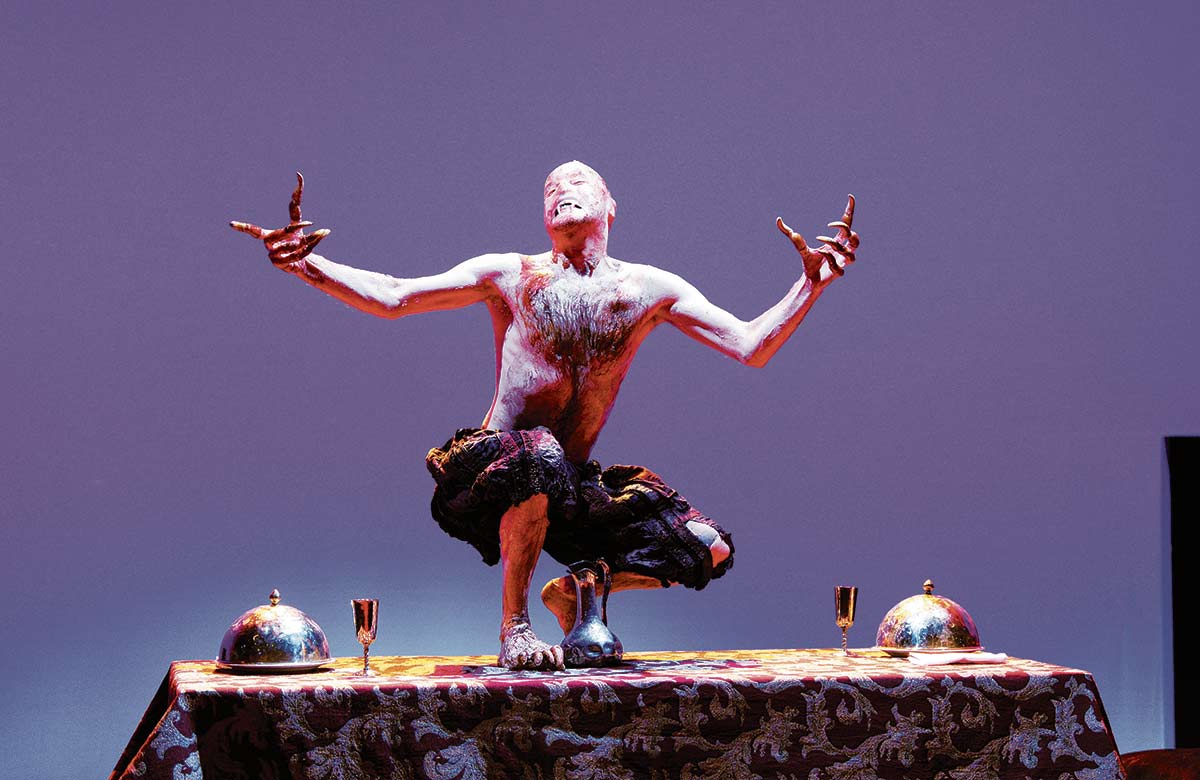

In 2008, Still returned to the Olivier with a production of Thomas Middleton’s The Revenger’s Tragedy, starring Rory Kinnear as the vengeful Vindice. The Olivier is a space where Still feels at home as a director. Its size doesn’t daunt her – quite the opposite. “I just love a big space,” she says. The Olivier is “such an inviting and strangely intimate place, and actors find it very comfortable”. In some ways, the stage at the Shipwright reminds her of the Olivier – the way the audience is wrapped around the stage, with the garden and the river behind them.

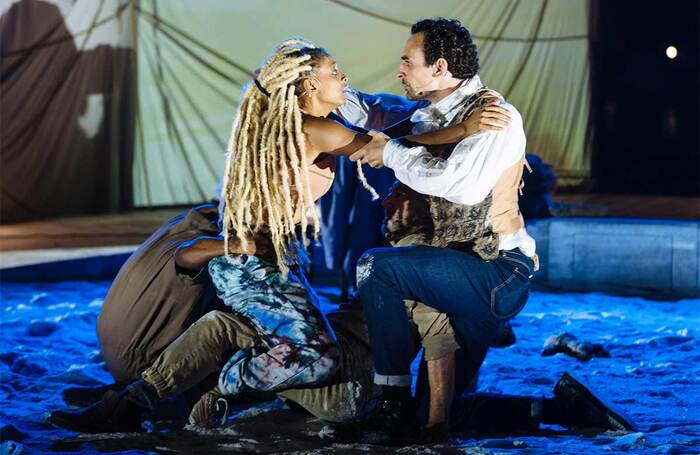

Her 2016 production of Cymbeline for the Royal Shakespeare Company was forged in a time of national and global instability and upheaval. It was the year of the Brexit referendum, Trump’s ascendancy, war in Syria and a growing migrant crisis in Europe. She created a bleak dystopian take on the play with Gillian Bevan playing Cymbeline. She didn’t have to do much to make this play about Britain’s decision to distance itself from the orbit of Rome feel relevant. “It’s all there in the text,” she says. “There’s an insularity that comes about through being an island. And there is a sense of exceptionalism that seems to prevail – the fallout of that insularity.”

The imagination-and-adaptation question

Literary adaptation has played a large part in Still’s career: in addition to Coram Boy, she has directed productions of Captain Corelli’s Mandolin, Alice Sebold’s The Lovely Bones and a two-part staging of Elena Ferrante’s My Brilliant Friend, each adapted by different writers – Rona Munro, Bryony Lavery and April de Angelis. My Brilliant Friend, based on Ferrante’s four Naples-set novels, opened at the Rose Theatre in Kingston – another space Still adores – in 2017, before transferring to the National Theatre in 2019, where it once again filled the Olivier.

She felt a responsibility in bringing these books that people hold so dear to the stage. When she first read them, she was “totally blown away”. The thing about those novels, she says, “is there is a weird effect of your own memories getting cross-fertilised with the world of the characters in the book”. She felt that was the way into them. When you’re reading them, “they don’t belong to Elena, they belong to you. They start to occupy your imagination.”

It was important to capture that, to create a theatre experience that was as “economic and distilled as possible, and let the audience fill in the details with their own imaginations”.

One thing she was clear on was she didn’t want the British and Irish actors doing Italian accents. “I do sometimes think: ‘Why do we do adaptations?’” she says, “but a story is a story and different forms invite different kinds of reactions and experiences.” She thinks Ferrante, whose identity has never been disclosed, saw it, and she hopes “she/he/they were pleased”.

Still has directed at Glyndebourne several times over the years, with Rusalka in 2009, The Cunning Little Vixen in 2012 and, most recently, Ethel Smyth’s The Wreckers, an opera that was last professionally staged in the UK in 1939. Her production afforded most audiences the first opportunity to see it, and The Stage’s opera critic described the result as “a triumph” and a “vindication of Ethel Smyth’s genius”. Usually, with opera, Still explains, there is a sense of familiarity, but in the case of The Wreckers, everyone was coming to it fresh. On the first day of rehearsals, they were “still learning the music, still trying to understand what was happening and what was needed”. It was an amazing experience “for all of us to be in a room learning together,” she says, and was very different to past opera productions she had worked on because she didn’t know the orchestration. It was only when the orchestra first played it that she started to get a real sense of it. When the orchestral sounds come in, she explains, “all these different layers begin to emerge”.

Having worked in the industry for more than 30 years, what changes has she noticed? Still does worry that when she’s applying for grants from Arts Council England “there’s less interest in the actual art”. She’s also increasingly aware, at the age of 60, of ageism in the industry.

But she sees her cross-disciplinary approach to theatre, a reluctance to self-categorise or pick one path and stick to it, becoming increasingly prevalent. Her own journey was fuelled not by ambition but by curiosity and the “feeling that I have always been a little bit on the outside”. There was pressure to have a clear answer to the question:

“Are you a designer? Are you a director? Are you a choreographer?” This made her stubborn: “I didn’t want to define myself.” Now, however, practitioners call themselves theatremakers. “It’s much more encouraged and theatre practitioners have to be very polymathic in order to survive. I think it’s wonderful.”

At the same time, she is struck by the passion and compassion she sees in the work being made at the moment: “Work that makes you really think and could hopefully have an impact on us and change us.” This is more important than ever. “It is a such a desperate world at the moment. I think a lot of work is driven by anguish.” This project, she says of The Gretchen Question, “is driven by that anguish, guilt, shame and regret”. But she thinks that people are “working out that making art is activism”, and that activism can take different forms. “I love making work that feels like it has an active role and tries to have an impact on society in some way.”

CV Melly Still

Born: 1962, Cambridge

Training: York St John University

Landmark productions:

• Coram Boy, National Theatre, London (2005); Broadway (2007)

• The Revenger’s Tragedy, National Theatre (2008)

• Cymbeline, Royal Shakespeare Company, Stratford-upon-Avon (2016)

• My Brilliant Friend, Rose Theatre, London (2017); National Theatre (2019)

• The Lovely Bones, UK tour (2018)

• The Wreckers, Glyndebourne (2022)

The Gretchen Question is at the Shipwright theatre, London, until October 2

Big Interviews

Recommended for you

Opinion

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99