Tim Bano

Tim BanoTim Bano is an award-winning arts journalist who has also written for the Guardian and Time Out, and worked as a producer on BBC Radio 4. ...full bio

With his work spanning opera, theatre, television, film and circus, the acclaimed director is in constant demand. He tells Tim Bano about his extensive career, the importance of laughter, collaborating with other directors, why clowning is the backbone of his work, and of his decade-long association with Giffords Circus, whose latest show ¡Carpa! is now on tour

There’s something familiar about Cal McCrystal’s face: the bright eyes, occasional raised brow, semi-permanent cheeky glint. It’s only when we start talking about his long career as a comedy actor and director – responsible for the funniest bits of some of the funniest films and plays of the past 15 years or so – that it becomes clear where I’ve seen him before. “I was directing an opera and I got a call at lunchtime from Paul King, who was directing the first Paddington film. He said: ‘Cal, you’ve got to get here straight away, we need a scene where Paddington gets stuck in some Sellotape.’ In the evening, after rehearsals, I jumped into a taxi and went to Covent Garden where they were waiting for me in a studio. I put on a very tight motion-capture suit with little dots all over it and said: ‘Okay, where’s the Sellotape?’ Then I just went crazy.”

That scene, along with several other comedy sequences, went into the Paddington film almost exactly as Cal performed it, his facial expressions and his daft actions faithfully rendered in ursine form.

McCrystal’s move into film – he’s developed comedy scenes for The Amazing Spider-Man 2, The World’s End and The Dictator as well as a film best passed over without too much comment, the notorious Cats – was a relatively late shift after decades as a comedy actor and director in theatre and TV. He’s now attached to three films as director, to add to his slate of well-received circus and opera productions.

Making people laugh

In person at the Ivy Club, McCrystal is not the goofy clown some might expect from the credits he has amassed. During rehearsals for One Man, Two Guvnors in 2011, on which McCrystal worked as comedy director, Nicholas Hytner said he “rarely breaks into anything warmer than a wintry smile”. Like many Gaulier-trained clowns, McCrystal remains earnest when he talks about making people laugh. “That old saying is true,” he explains. “Comedy is a serious business.”

As a child, McCrystal moved from Belfast to New Jersey to Totteridge, following the work of his father, a senior journalist for the Sunday Times. “I think my dad always hoped I would be a writer. When I wanted to be an actor, he thought: ‘What is this strange thing?’ ”

Although desperate to become an actor, his parents were “a little bit worried about it”. They told him he needed something to fall back on, so he enrolled in catering college. “It’s a nice skill to have. I like to cook. But luckily, I’ve never had to fall back on it.”

In 1978, McCrystal won a place at the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama to study acting. He found it a frustrating experience. While other drama schools were exploring experimental techniques such as physical theatre, the academy stuck to the classics: Ancient Greece, Shakespeare, Chekhov. “Pinter was as modern as it got,” he says.

“I was frustrated because they didn’t take me seriously as an actor. I remember the principal saying to me at one point: ‘The trouble with you is that when you walk on to the stage, the audience immediately likes you, and it means you don’t have to work very hard.’ I said: ‘Oh, I see. That’s not going to help me when I play Hamlet.’ He laughed and said: ‘You will never play Hamlet.’ Maybe he was right in a way, but it’s not a good thing to say to a student. Everyone has a Hamlet, and certainly every clown has a Hamlet, because it’s such a human role.”

‘I couldn’t go into a McDonald’s for months, as everyone would say: Are you here for a McDonald’s breakfast?’

Immediately after graduating, Yorkshire TV offered McCrystal a contract to present children’s TV programmes for ITV. That led to a healthy 10-year spree of work, encompassing film, radio, music hall and rep, as well as many TV adverts: Honda, Boots, building societies, several brands of lager, McDonald’s breakfast. “I couldn’t go into McDonald’s for months because everyone would say: ‘Are you here for a McDonald’s breakfast?’ ”

Preparation process

His favourite advert was for Hamlet Cigars, which involved a rigorous preparation process. “We went through the paces at the audition and then as I was leaving they said: ‘Oh Cal, you do actually smoke, don’t you?’ I went: ‘Well, I’m trying to give up.’ I’d never smoked anything in my life. So I remember before we did the shoot, buying a packet of cigarettes and trying to smoke them and feeling absolutely sick. When we actually did the shoot, the first shot of the day was at eight in the morning with me smoking a cigar. I smoked eight of them. I was green for the rest of the day.”

Those adverts not only allowed McCrystal to stay limber as a performer, they also subsidised doing the rep work that he loved. Although he says commercial directors “are not the best”, he remembers one note he received for a restaurant advert. “He just kept saying: ‘Do less, do less, do less,’ until I was doing nothing at all. And then he said again: ‘Do less.’ I knew what he wanted, and it was such a great note. I use that a lot. It’s not in conflict with big physical comedy stuff, because to make that genuinely funny there has to be a truth behind it. The way I layer my productions is that there’s always the show that’s going on, and then there’s the subtextual layer of the politics between the actors. That requires a great deal of restraint and subtlety.”

Cal McCrystal Q&A

What was your first non-theatre job?

When I was a teenager, I had a Saturday job in the local pet shop. I earned £3 a day but would have paid them to let me work there.

What was your first professional theatre job?

Panto at the Queen’s Theatre, Hornchurch.

What do you wish someone had told you when you were starting out?

That I’d still be thriving in the business all these years later.

Who or what was your biggest influence?

Philippe Gaulier, and the films of Blake Edwards and Mel Brooks.

What is your best advice for auditions?

Assume that they really like you and want it to work out. Directors should try to make sure that every auditionee has a good experience.

If you hadn’t been a director, what would you have been?

I’d have stayed an actor.

In 1989, an advert in Time Out took McCrystal to a clowning workshop led by Pierre Byland, one of Switzerland’s most famous clowns. Byland was a gateway to clown master Philippe Gaulier, whose London summer workshop McCrystal attended and adored, although not without some initial terror at facing one of the performing world’s most formidable figures.

“When I met Gaulier, I was 28 years old and I had already made a living as an actor, making people laugh. I had such a terrible fear that this great man was going to say to me that I’m not actually funny. But the way he worked was that you would get up to try some exercise he was doing, and if it didn’t work, he’d say: ‘Not funny.’ Once you’ve heard that honesty, you can let go of all your fears. Somebody just said the worst thing to me that they could ever say and I’m fine. And I’ll start from nowhere tomorrow, and maybe I’ll get somewhere. He’s not vindictive, he’s not malicious. He’s actually a very kind and caring teacher. But he’s very, very honest.”

The two men got on well and clowning has been the backbone of McCrystal’s work ever since. He worked with acclaimed companies Peepolykus and Spymonkey, and in 1998 was even approached by Julian Barratt and Noel Fielding, who asked if he would direct a show they were creating called The Mighty Boosh.

For McCrystal, making people laugh is the most important thing. Often that means he has no qualms about tinkering with a text if he thinks he can make it funnier. In his production of HMS Pinafore at English National Opera last year, the addition of an old woman irked a few critics, although the production was well received.

‘Apart from One Man, Two Guvnors, it has never been a happy experience to work with another director. I have my own way of doing things’

In 2004, he directed a production of Kafka’s Dick by Alan Bennett. “I love Bennett, so I said I’d love to do it without reading the play carefully. When it came to the last scene, I realised it was absolutely ghastly. So I rewrote it. The Telegraph review said: ‘Cal McCrystal should learn not to tamper with the work of those more talented than he.’ That was a slap on the wrist.”

Critics are one thing, but drawing the ire of the writer is altogether more anxiety-inducing. Thankfully for McCrystal, Bennett never saw that production of Kafka’s Dick. But in 2013, he didn’t get off so lightly. Alan Ayckbourn gave him permission to stage the 50th-anniversary revival of lesser-known play Mr Whatnot, which had been a notorious flop when it opened in the West End in 1964 despite starring Ronnie Barker.

“It really needed rewriting, but Ayckbourn doesn’t like having a word changed. I thought: ‘Well, he’ll never come, so he’ll never find out. On the opening night, I went into the bar and there he was. I went up to him and said: ‘Hello Sir Alan, lovely to meet you. Listen, I’m really sorry, but I’ve rewritten it. I just couldn’t make a lot of it work because it felt very dated. I’ve kept all the good bits, though.’ He said: ‘Oh, I see.’ I watched him in the audience and he laughed a lot. Then at the end, I said to him: ‘So what did you think?’ He said: ‘It was like looking through a much-loved old photograph album… with a surprise on every page.’ ”

Circus shows

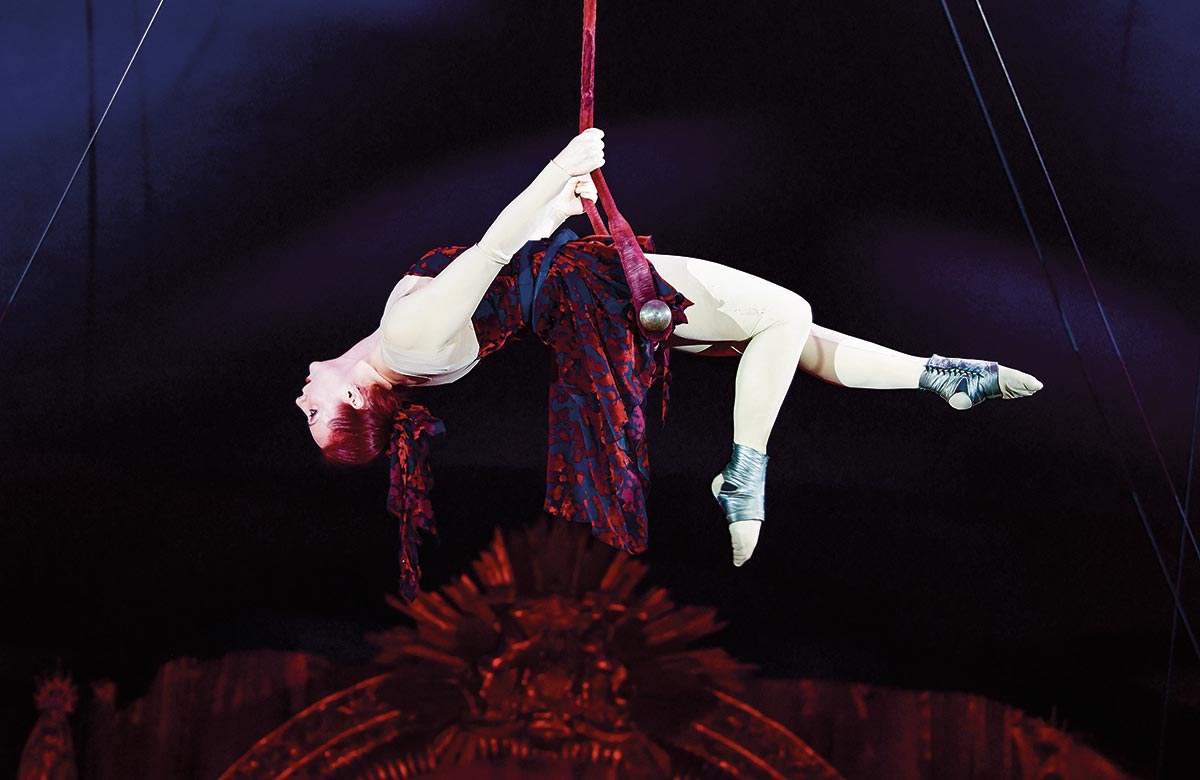

TV and stage aren’t where McCrystal’s influence ends. Since directing a show for Cirque du Soleil in 2002, he has maintained a strong line in circus shows. The new show from Giffords Circus, ¡Carpa!, marks a decade directing the company’s output. His involvement started after a chance meeting with founder Nell Gifford.

“A friend introduced us, we talked for 20 minutes, and she offered me a job. She’s the most significant collaborator of my life. She made the whole experience of going to the circus something beautiful. She trusted me with the shows, but the whole ambience of Giffords is Nell’s: the village-green feel, the stipulation that we only ever go to beautiful places. And then when she got cancer, she was so generous about sharing her experiences. She left her mark in so many ways.”

‘Nell Gifford is the most significant collaborator of my life. She made going to the circus a beautiful experience’

Giffords Circus bloomed out of Nell’s love of horses and horse riding, performing in the shows as well as being in charge of the company. That continued right to the end of her life. “I remember an opening night in London for one of the shows, and she’d had a massive dose of chemo that night. She said to me: ‘I don’t think I can get on a horse.’ I said: ‘I’m going to lift you on to that horse if I have to, and you’re going in the ring.’ She did, and it was fine. Even at the end, she was still absolutely pushing through.”

When Gifford died in 2019, aged 46, she left McCrystal in charge of directing future shows. “I was with her in the hospital and she said: ‘Can this continue without me?’ I said yes, it can, because she’d spent years assembling a team of people who could make the right choices. She would have loved our last two shows.”

Just before meeting Gifford, McCrystal had been through what he now calls “a life-altering experience”. In 2011, the National Theatre opened one of its most successful ever shows, One Man, Two Guvnors. Richard Bean had written the script, based on the 18th-century commedia dell’arte play The Servant of Two Masters by Carlo Goldoni, and Nicholas Hytner was directing James Corden in the main role.

Hytner brought McCrystal in to “do the clowning elements and create a comic vocabulary for the entire show”. In terms of how that translated into the play, he essentially had free rein in the first half, culminating in the spectacular restaurant scene.

Working at the National was a dream for McCrystal, but one he never thought would come to fruition because the National “tended not to do clowning stuff”. He is candid about the fact that there were tensions at first. “It’s never an easy relationship when there are two directors in the room. But while Nick didn’t always like what I was doing, he trusted me and it paid off.”

Success story

After the show’s phenomenal success – it transferred to the West End and Broadway, an NT Live broadcast exposed it to huge new audiences, and there was a rediscovery of its brilliance during the pandemic when NT at Home showed it for free online – directors were knocking down McCrystal’s door to come on board as comedy director on various shows.

“But I won’t ever do it again. I’ve had very difficult experiences with a couple of directors who needed me. I made the productions what they were and then they have been very ungenerous about the fact that I directed them. Apart from One Man, Two Guvnors, it has never been a happy experience to work with another director because I’ve got my own way of doing things. Also, if a director asks for a comedy director, you can take from that they’re not particularly good at comedy. I always think it’s a bit strange. If somebody’s directing a tragedy, they don’t have a tragedy director.”

McCrystal worked closely on One Man, Two Guvnors with Corden and this developed into a very productive relationship. It also led to Corden bringing McCrystal in to provide comedy consultancy on the notorious Cats movie.

Did McCrystal watch the film? “I did. It was terrible. But it was very difficult to tell when we were working on it that it would be terrible because everyone was in green motion-capture leotards. We didn’t know fully what it was going to look like in the end. I did say to Tom Hooper, who I got on very well with, that I thought the whole thing would come off best if played with a twinkle in the eye rather than as heavy drama. But I don’t think that quite sunk in.”

Still, most of the other films that have used McCrystal as a comedy consultant have been successes. “I don’t mind working with other directors on films because it’s not my world. I don’t know how to make a film,” he says.

And perhaps most successful of all are those two Paddington films. “It’s a lovely way to be memorialised, as a cartoon bear.”

CV Cal McCrystal

Born: 1959, Belfast

Training: Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama, Ecole Philippe Gaulier

Landmark productions:

• The Mighty Boosh, Edinburgh Fringe (1998)

• Varekai, Cirque du Soleil (2002)

• Stiff, Spymonkey (2000)

• Cooped, Spymonkey (2001)

• Let the Donkey Go, Peepolykus (1996)

• Office Party, Barbican (2008)

• One Man, Two Guvnors, National Theatre (2011)

• Zumanity, Cirque du Soleil (2013)

• Don Quixote, Royal Shakespeare Company (2016)

• Iolanthe, English National Opera (2018)

• HMS Pinafore, English National Opera (2021)

Awards:

Perrier award for best newcomer at the Edinburgh Comedy Awards for The Mighty Boosh

Agent: Jamie Hendry/Creative House Management

Giffords Circus’ ¡Carpa! is now touring the UK. For further details, visit: giffordscircus.com/theshow

Big Interviews

Recommended for you

Opinion

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99