Nancy Carroll

Liz Hoggard

Liz HoggardOnce labelled the “best actress you’ve never heard of”, Olivier award winner Nancy Carroll continues to attract plaudits. As she prepares to play Hester Collyer in a revival of Terence Rattigan’s The Deep Blue Sea, Liz Hoggard finds a performer at ease as she embraces a defining role for female sexuality

Nancy Carroll is talking about the importance of erotic desire. “It’s a process of ownership that starts when puberty hits and finishes when you die. And it doesn’t stop when you hit 40, and it doesn’t stop with the menopause, you just keep going. And it’s about being allowed to own your essence, and go on a journey with it. And part of that essence is your sexuality, what floats your boat, what makes you laugh. And we may have to recalibrate a little bit more as we age, but long may it continue. I hope that I’m shagging like a rabbit into my 90s.”

It feels slightly surreal to be chatting about female pleasure over Pret sandwiches in the chilly basement of London’s American Church. But, actually, it’s a valid topic for rehearsals.

Carroll is about to star as Hester Collyer, the middle-aged woman who leaves her husband for a younger lover, in Terence Rattigan’s The Deep Blue Sea, considered one of 20th-century theatre’s best parts for a woman.

Carroll has long dreamed of playing Hester, ever since she won the Olivier and Evening Standard awards for best actress for her heartbreaking performance in the National’s 2010 production of Rattigan’s After the Dance. She played Joan, opposite Benedict Cumberbatch as her onstage husband David.

d3s3zh7icgjwgd.cloudfront.net/AfcTemp/MediaFiles/2019/06/12104656/After-The-Dance-Lyttelton-03-100x65.jpg 100w,

d3s3zh7icgjwgd.cloudfront.net/AfcTemp/MediaFiles/2019/06/12104656/After-The-Dance-Lyttelton-03-100x65.jpg 100w,

There was talk of the show going to Broadway, but the timing didn’t work for Cumberbatch. At the time, Carroll admitted she was deeply disappointed.

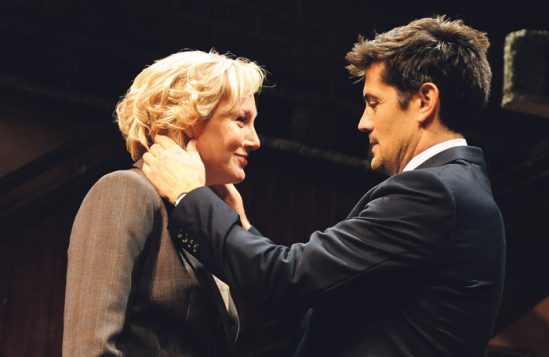

But now, aged 44, she gets to play the lead in Chichester Festival Theatre’s revival of Rattigan’s 1952 masterpiece. The production is directed by Paul Foster (whose recent credits include A Little Night Music at the Watermill Theatre and Kiss Me, Kate at Sheffield’s Crucible Theatre), with Hadley Fraser as her lover Freddie, and Gerald Kyd as her husband, William Collyer. When we meet on day five of rehearsals, Carroll admits to nerves: “I’ve wanted to do it for a long time, although now I’m here it’s a bit more daunting.”

Out of the comfort zone

There is a modesty to Carroll – a Sunday Times interview with her was once headlined “The best actress you’ve never heard of”. In fact, she is a class act who directors queue up to work with. Her roles include The Moderate Soprano, where she gave an exquisite performance as soprano Audrey Mildmay, the wife of John Christie who founded Glyndebourne; and Anna the sexy photographer in David Leveaux’s revival of Closer at the Donmar. TV viewers know her from the Father Brown series, based on the GK Chesterton stories, in which she played the haughty Lady Felicia.

d3s3zh7icgjwgd.cloudfront.net/AfcTemp/MediaFiles/2018/03/26125106/Md-Sprno-47-Edit-100x65.png 100w,

d3s3zh7icgjwgd.cloudfront.net/AfcTemp/MediaFiles/2018/03/26125106/Md-Sprno-47-Edit-100x65.png 100w,

But The Deep Blue Sea is a new challenge. Rattigan based the play, in part, on his own clandestine love triangle. In the late 1930s, Rattigan had begun a relationship with a young actor called Kenneth Morgan. Their tempestuous on-off affair ended in 1945, when Rattigan took up with Tory MP Henry ‘Chips’ Channon. Morgan started seeing someone else. One day in February 1949, Rattigan received a message that Morgan had killed himself. Rattigan was devastated, but began to conceive an idea for a play.

“It was very much written from the point of view of forbidden love. And that’s quite an interesting thing to explore in a modern age,” says Caroll. To be gay in the 1950s, when homosexuality was still illegal, was to choose sexual love, she stresses. “You’ve made the choice to be truthful to yourself and say: ‘No, that’s what makes me happy. That’s what fulfils me, loving that man. Even though the police tell me it’s wrong.’”

Set in 1951 in Ladbroke Grove, the play takes place over one day, in one room. Hester’s neighbours find her unconscious in her bedsit; she has taken an overdose in front of the gas fire. They inform her husband – a High Court judge. But Hester has left her husband to embark upon a passionate affair with young ex-RAF pilot Freddie Page.

“She’s left her husband for another man – whom she admits and realises doesn’t love her. At least not in the way she has used as her excuse for abandoning her marriage. What’s really interesting is Rattigan doesn’t pass judgement. She isn’t seen as the baddie. If the production is done well, Freddie isn’t the baddie either, and her husband William isn’t sexless.”

d3s3zh7icgjwgd.cloudfront.net/AfcTemp/MediaFiles/2019/06/12111352/Hadley-Fraser-Nancy-Carroll-in-rehearsal-for-The-Deep-Blue-Sea-at-Chichester-Festival-Theatre-Photo-Manuel-Harlan-081-100x65.jpg 100w,

d3s3zh7icgjwgd.cloudfront.net/AfcTemp/MediaFiles/2019/06/12111352/Hadley-Fraser-Nancy-Carroll-in-rehearsal-for-The-Deep-Blue-Sea-at-Chichester-Festival-Theatre-Photo-Manuel-Harlan-081-100x65.jpg 100w,

When he came to write his love triangle, Rattigan made his main protagonist a woman. But Hester is anything but a male ‘cypher’. She’s witty, manipulative, and insists on her right to pleasure. “Women weren’t supposed to get pleasure from sex. And if you did you were a guttersnipe,” Carroll says in mock horror. “Because that wasn’t what it was there for, it was within marriage and it was to procreate.”

The play has resonances for a modern audience, she thinks, on the issue of “whether as an older woman you allow yourself to be a sexual creature. And whether the world permits you to be a sexual creature. It’s still quite a helpful thing to teach our daughters that it’s okay to ask for pleasure.”

The first performance of The Deep Blue Sea in 1952 was a huge success. But, gradually, it disappeared from the repertoire as Rattigan was overtaken by the Angry Young Men of the 1960s. Today, it’s regarded as a modern classic. Helen McCrory gave a blistering performance in Carrie Cracknell’s 2016 production at the National. Rachel Weisz played Hester in Terrence Davies’ 2011 film.

Carroll deliberately didn’t watch the National production – “Helen is so magnificent” – but the last Chichester production was only eight years ago (with Amanda Root as Hester). “So you have to warrant the re-imagining. And I hope Chichester has a different enough audience to the National, so there’ll be a whole new set of eyes having a look.”

And a lot has happened since 2016. “The post-#MeToo generation will see a woman really struggling to stand up for what she believes in. It is a joy to do a play about forbidden love at this particular point because then you do focus on other things. It’s not that we live in a society where love is forbidden, it’s a bit more permissive than that. However, there is a fascistic backlash globally against ‘unorthodox’ – in their eyes – sexualities. We seem to be reverting at the edges.”

I told the director that it was important for British theatre and feminism that he let me vault the sofa

With her auburn hair and porcelain complexion, Carroll has made her career playing aristocrats. But she can also release a raw physicality on stage. She describes acting as a way of getting out of her comfort zone. “As long as my body serves me well, I just want to be able to use it. It’s my tool bag.” Appearing in The Duck House in 2013, a farce about the MPs’ expenses scandal, she says she adored the slapstick. “I absolutely insisted on doing physical comedy, some of which the director Terry Johnson didn’t really want me to do. I remember making a really big fuss. It’s always the men who get the really good physical comedy. I don’t think any women fell down the stairs in One Man, Two Guvnors, for example. So I said: ‘It’s important for British theatre and for feminism that you let me vault this sofa.’ And I did it, and I felt really good about it.”

There was even a plan for her to vault off a small trampoline across the set and fly past some glass doors, but sadly that was vetoed by the producer for insurance purposes “because I wasn’t a young chick anymore, which was slightly depressing”.

Breaking taboos

Equally, she observes, over the age of 40, parts for women do start to dwindle, or certainly change. “It was a real moment when I did Closer. I was 41 at the time and there was that recognition that I represented ‘woman’ and Rachel Redford playing the young Alice represented ‘girl’. And the voyeuristic nature of Patrick Marber’s play means that you just have to expect that you’re going to be looked at because it’s through the eyes of the guys. And I had a moment of feeling like a middle-aged bag lady. And I went back to my husband and he said: ‘Yes, but it’s like you’re in a room with alcoholics and she’s brought this massive crate of beer, and you’re the bacon sandwiches that they will need the next morning’. And I thought: ‘Yeah I’m a bacon sandwich’,” she deadpans.

She think actresses of her generation have been given a bit of a raw deal. “No disrespect to the generation before, but it’s been a whole lot of mixed messages. It’s: ‘Let’s lie about our age. Let’s spend lots of money changing what our skin is doing, and our eyeballs and everything else. And let’s not talk about sex after a certain age.’ Fuck that! I’m sorry, yes, I love having a good facial, but there’s a point where you have to go: ‘This is what’s happening guys, and okay it isn’t quite as pert as it was however many years ago, but it’s still great, and it still moves.’ ”

It’s important that we break taboos and give permission for the next generation, she says, warming to her theme. “It’s a bit like miscarriage or fertility treatment. I went through all of that, as a lot of women do, and even now it takes people’s breath away when you say: ‘Oh yes, I had a miscarriage.’ One of my best friends is Greek and she says: ‘You are rubbish in your country. We talk about this all the time. How else does anybody know?’ ”

Carroll has put her body through a lot as an actor. She was eight weeks’ pregnant by the end of After the Dance and went straight to the Almeida to star in House of Games for three months (“by which point elastic waistlines were required”). During the run, her nausea was so bad that one night she was sick on her co-star. By the time the Oliviers came round, she was eight months’ pregnant. The shock of winning set off contractions and she hardly made it to the podium before she had to stagger into a taxi and go home to prepare to give birth.

“He was my second baby and the body goes: ‘Oh yes, I remember’ and flops out quite quickly,” she recalls.

d3s3zh7icgjwgd.cloudfront.net/AfcTemp/MediaFiles/2019/06/12112254/House-Of-Games-Almeida-176-100x65.jpg 100w,

d3s3zh7icgjwgd.cloudfront.net/AfcTemp/MediaFiles/2019/06/12112254/House-Of-Games-Almeida-176-100x65.jpg 100w,

Named after the 1930s showgirl and movie star (her father was a film buff), she grew up in Herne Hill, south London, and went to Alleyn’s School, where she was in all of the plays. After school, she followed her parents – both graphic designers – and went to study fine art.

She spent a year in Italy learning how to mix her own paints and stretch canvases before starting at Leeds University, where she found the course too conceptual. So she applied to LAMDA, paying for her first year with her fee from a tampon advert.

Graduating in 1998, her first professional job was in the film An Ideal Husband with Cate Blanchett and Rupert Everett. “I thought, ‘Well, this is all right.’ And of course it didn’t carry on like that at all.” Indeed, she admits that, even at her level, the phone sometimes doesn’t ring. She fights feeling powerless by painting, or enthusing about non-acting projects. “I often think about different businesses and things, it’s a way for me of regaining control. It’s important for you to reassert your choice. There’s a terrible pressure we put on ourselves to pigeonhole our occupation. But actually it’s sort of up for grabs.”

Daring to fail is important, she stresses. “If you’re brave enough and don’t observe the boundaries we set for ourselves, you can have a go at anything. Fake it ’til you make it. There’s a wonderful poster up in one of my children’s classrooms that has the word FAIL – but it stands for First Attempt In Learning. Just have a go. If all else fails, I’d quite like to be an art teacher.”

Continues…

Q&A Nancy Carroll

What was your first non-theatre job?

I worked in a hat shop in Lavender Hill.

What was your first professional theatre job?

A tiny weeny part in the Oliver Parker film An Ideal Husband in 1999. My first stage production was The Winter’s Tale at the RSC.

What do you wish someone had told you when you were starting out?

Take care of your teeth and keep hold of your mates.

Who or what was your biggest influence?

My husband, my mum. Various directors along the way.

What’s your best advice for auditions?

That decisions are made beyond anything we can possibly have any control over. They’re chemical and you just have to be yourself. Don’t try to control the environment. Just be present, and allow yourself to be looked at.

If you hadn’t been an actor, what would you have been?

I have five years’ fine art training so I probably would have done something to do with art. I still paint and I’d love to teach kids art.

Do you have any theatrical superstitions or rituals?

I’m terrified of ghosts. If someone says: “There’s a ghost in the theatre”, I really struggle and can’t be alone.

Carroll joined the Royal Shakespeare Company in 2000, played Lady Percy in Henry IV Part One, Celia in As You Like It and Viola in Twelfth Night. She got together with her husband, the actor Jo Stone-Fewings, when they were both filmed as part of a touring troupe for the 2003 BBC documentary In Search of Shakespeare.

The couple met on the first day of rehearsals; nine days later they were engaged. “The thing I felt on meeting Jo was I’d been crashing my head against a brick wall for a number of years, and speaking the wrong language, and suddenly we spoke the same language. It was like we knew each other from before. I didn’t think: ‘Oh my God, I must walk towards this dramatic fling and burn myself until my legs fall off.’ I’d felt like I’d come home. For a long time I felt I was a high-maintenance pain in the arse,” she adds endearingly. “Now I know I’m a high maintenance pain in the arse, but I’m completely accepted.”

d3s3zh7icgjwgd.cloudfront.net/AfcTemp/MediaFiles/2019/06/12112640/AS-YOU-LIKE-IT-RST-19-7-100x65.jpg 100w,

d3s3zh7icgjwgd.cloudfront.net/AfcTemp/MediaFiles/2019/06/12112640/AS-YOU-LIKE-IT-RST-19-7-100x65.jpg 100w,

They married that year and have two children – Nelly, 11, and Arthur, 8. In 2006, they appeared on stage together in the West End farce See How They Run, with the family dog, now sadly deceased. And, in 2009, she appeared as Viola opposite her husband’s Orsino in an RSC production of Twelfth Night.

How does a marriage between two actors work? “The two things we try to do is laugh in the face of crisis. And also lovebomb the other person. A lot of situations just need more kindness and listening.”

Riffing on relationships

Friendship is important. Carroll credits the mates who fed her a glass of wine or gave a hug during tough times. She became great friends with John Lithgow when they appeared together in the National’s 2012 revival of Pinero’s The Magistrate. For the past seven years, they’ve smuggled Victorian pennies back and forth to each other through contacts and stage managers. “It’s a way of keeping in touch with people you loved working with.”

But, as a woman who got engaged in nine days, she clearly understands romantic coup de foudre. In Deep Blue Sea, Hester ‘knows’ immediately that her marriage is over when Freddie brushes her arm. “What’s so beautiful about the relationship between Freddie and Hester is that it’s quite animal. And everything about her relationship with her husband is entirely healthy apart from this huge void.”

We talk about the play’s ambiguous ending. Many productions end with a second suicide attempt. But in the National’s 2016 version, Carrie Cracknell had Hester frying herself an egg, on the fatal gas stove.

For Carroll it’s important that Hester can live “beyond hope” (as the play’s mysterious ex-doctor, Mr Miller, advises her). Yes she has sacrificed everything for sexual love. But rejection is not the end of the story. “Whatever you take from that experience, you take ownership of it, and it’s now part of you, and you don’t leave it with that man. It was your body that felt that. He awoke something in you, but it was your pleasure and your happiness,” Carroll says poetically. Then she adds, laughing, “I’m riffing. I don’t know how I’ll do that yet.”

I feel anxious about younger generations who have had social media and online porn enter their consciousness. It’s screwed up their idea of relationships

She despairs of the way sex has become performative today. “Watching younger generations who have had the influences of social media and online porn enter into their consciousness, it’s completely screwed up their idea of their relationships with their bodies and lovemaking. So in some ways we’ve been set back 50 years because we’re going to have to rebuild from this point about having a genuine relationship with your partner based on what you create together. There isn’t room for that in the current consciousness. It’s a real shame and something I feel anxious about, having a daughter.”

As I prepare to leave, she’s still pondering why Hester and Freddie really are “death to each other” as a couple. “I don’t know why they rile each other so much and yet are so entirely conjoined. But then we’re only on day five.” The Deep Blue Sea is a “big mess of a play because it doesn’t answer any questions”, she laughs. But, ultimately, it’s a love story where people from the higher echelons of society – the judge, the clergyman’s daughter, the spitfire pilot – turn out to be just as faulty as the rest of us.

“Rattigan puts you into this emotional car crash where you realise they are human and vulnerable and you’re watching them unravel. And you get that in After the Dance as well. At some point, he forces his audience to sit forward in their seats and engage. You have to go on this journey. It’s immersive and I love his writing for that.”

CV Nancy Carroll

Born: 1974, Cambridge

Training: Fine art at Leeds University. LAMDA 1995-98

Landmark productions:

• The Talking Cure, National Theatre (2003)

• Arcadia, Duke of York’s Theatre, London (2009)

• After the Dance, National Theatre (2010)

• House of Games, Almeida Theatre, London (2010)

• Closer, Donmar Theatre, London (2010)

• The Moderate Soprano, Hampstead Theatre (2015) and the Duke of York’s Theatre (2018)

Awards:

• Olivier and Evening Standard awards for best actress for After the Dance, 2010

Agent: Dallas Smith

The Deep Blue Sea runs at Minerva Theatre, Chichester, from June 21 to July 27. Full details: cft.org.uk

Big Interviews

Recommended for you

Opinion

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99