Woolf Works review

Triumphant return for Wayne McGregor’s game-changing ballet

It opens with a segment of a 1937 radio broadcast by Virginia Woolf, speaking in her pinched tones On Craftsmanship: “How can we combine the old words in new orders so that they survive, so that they create beauty,” she muses, referring to her own radical modernist approach to the novel.

The remarkable thing about Wayne McGregor’s three-act ballet is how successfully it takes Woolf’s richly complex words, rooted so deeply in interiority, and gives them “new order” in such a satisfying physical manifestation. When it premiered in 2015, it changed many people’s perception of a choreographer known mainly for a fascination with science and an insatiable passion for hyperextensions. Eight years on, it’s still a work that makes you catch your breath.

Partly, that’s due to the fact we’re watching Alessandra Ferri, who turns 60 in May, dancing the lead in two of these three discrete acts with a fluidity and luminosity that defies belief. McGregor built his ballet around Ferri as she came into an astonishing late second act of her ballet career, and she immerses herself utterly in the role of Woolf, pounded by emotions that range from giddy joy to the deepest despair. The Royal Ballet superstars Natalia Osipova and Marianela Nuñez will alternate with her during this latest run. It will be fascinating to see how they compare.

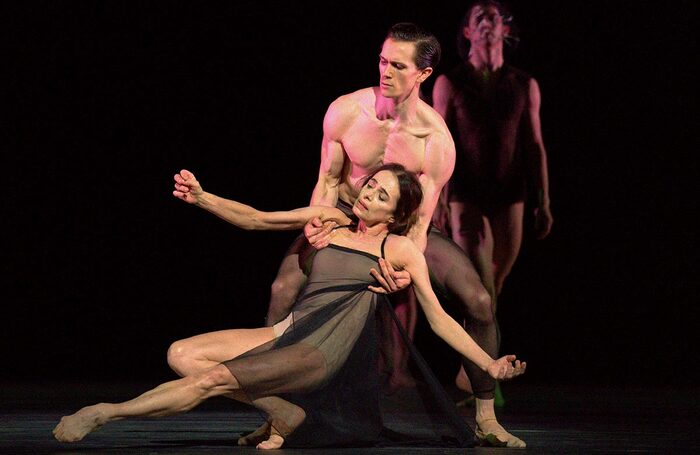

In I Now, I Then, based on the stream-of-consciousness novel Mrs Dalloway, Ferri is partly Woolf, enveloped in her own creation, and partly the novel’s main character, Clarissa Dalloway, the society hostess lost in reveries. Past and present weave and collide. Ferri depicts fracturing mental health with shooting limbs and a fraught, tussling duet. Then she is carried off by blissful memories of a past beau and a treasured kiss.

Continues...

Yasmine Naghdi sparkles as the young Clarissa, whirling brightly in gauzy skirts. Francesca Hayward is a fierce, darting Sally. Stalking through it all, though, is Septimus, the shell-shocked soldier who acts as a kind of dark reflection of Clarissa. Calvin Richardson moves with a sense of battered, weary defeat through choreography that evokes a collapsing mind, powerful and full of pathos, especially when partnering his lost comrade (Joseph Sissens).

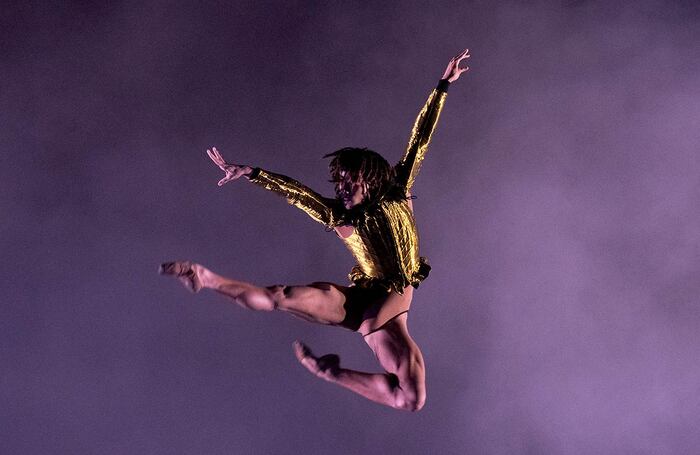

Becomings takes its cues from Orlando, Woolf’s dazzlingly defiant, shape-shifting novel of 1928, whose protagonist lives for three centuries switching from man to woman. Bodily transformation being right up McGregor’s choreographic street, here is where he fully unleashes his trademark contortions on the 12 dancers. They careen about in Moritz Junge’s retro-futuristic costumes, on a stage mapped out with sweeping laser beams, as Max Richter’s entrancing score plays through 17 variations of La Folia. Surface glitter aplenty, then – particularly when Fumi Kaneko struts on stage and sends the sensuality of a notably twisty duet stratospheric. But frustratingly, it doesn’t ever seem to find a deeper resonance.

Tuesday, by contrast, is almost overwhelming in its poignancy and emotional depths. Partly echoing Woolf’s densely textured 1931 novel The Waves, it is also a meditation on the author’s death by suicide. A greyscale video frieze of pounding waves dominates above the dancers, and Woolf’s last note to her husband is our introduction to the piece, read by Gillian Anderson.

Then we are swept away by Ferri’s return as Woolf. William Bracewell partners her with a desperate thwarted protectiveness; a group of playing children throw her into a bruised, brooding contemplation of her childlessness. The dancers mass together, echoing the churning waves above them, and Ferri is caught in their maelstrom; buffeted, tossed, eventually finding stillness. It’s an absolute heartbreaker of a piece – and Ferri imbues the role with the experiences, loves and losses of decades.

More Reviews

Recommended for you

More Reviews

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £5.99