The Importance of Being Earnest review

Flamboyantly queer take on Wilde’s well-loved comedy is arch, high-camp fun

Oscar Wilde’s best-known play is a frothy concoction served with a saucy wink, its risqué jokes baiting Victorian hypocrisy and respectability artfully secreted up its silken sleeve. Max Webster’s flamboyant revival makes its queerness full frontal, with an aesthetic of drag and high camp that pursues Wilde’s motifs of artifice and doubleness to their logical conclusion. Gender, it suggests, is both a construct and performative; no one involved in the self-conscious games depicted is for one millisecond in earnest.

That studied air of triviality is a delicate mechanism in any production of this comedy, but by making his reading so arch – with actors who literally wink at the audience as they deliver aphorisms so familiar that we could recite them by heart – Webster raises the stakes. We’re not being invited to care about or invest in this world or its characters – so they had better be entertaining.

Happily, they are, although there’s so much comic business that at times the pace perilously slackens, and restoring Wilde’s originally intended four-act structure and extra material was probably a mistake; over nearly three hours, this gossamer creation gets stretched very thin indeed, especially at the denouement, which here feels interminable. But there’s so much fizz and sparkle in the staging, and such charm, cheek and flair from the cast, that we’re consistently tickled and ultimately won over.

Continues...

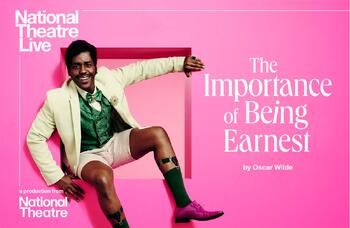

Rae Smith’s design of a faux gilded proscenium arch, topped with a plaster moulding of a bouquet of decidedly phallic vegetables, features a red velvet curtain that slices between scenes, lest we forget that nothing we’re watching is real. Ncuti Gatwa’s Algernon, sleek and gleeful as a cat licking cream off its whiskers, makes his first appearance in a hot-pink ballgown, simulating a Dr Dre track on piano while striking poses; the country manor house of Hugh Skinner’s fidgety, sulky Jack has an astroturf lawn with Disneyish oversized flowers against an improbably blue sky.

These two frolicking bachelors seem more interested in each other than in the women they set out to wed, which lends a slightly alarming twist to the familial revelations of the final scene; and the bitchy tea-table spat between Eliza Scanlan’s brattish Cecily and Ronkẹ Adékọluẹ́jọ́’s mischievously assertive Gwendolen spirals into erotic excitement. Both women are overtly sexually charged, Adékọluẹ́jọ́ devouring the contents of Jack’s trousers with her wide eyes; for the men, the marriages seem to be more a matter of economic and social convenience.

Presiding over it all, Sharon D Clarke’s Lady Bracknell is a formidable Caribbean matriarch, her withering putdowns delivered with lethal elegance; her delivery of the infamous “A handbag?” line is refreshingly understated, yet dripping with disdain. There’s vivid support from Julian Bleach as a pair of cadaverous manservants, and from Richard Cant’s Canon Chasuble and Amanda Lawrence’s schoolteacher Miss Prism, both of them so quivering with repressed desire that they can barely trust themselves to be in the same room. The prevailing air of unreality means that, for all its nudge-nudge naughtiness, the production is more sweet and silly than it is sexy. But it has a celebratory sense of fun, carried off in style.

More Reviews

Recommended for you

More Reviews

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99