Romeo and Julie review

Sweet and savage working-class love story scintillatingly writes its own rules

Gary Owen’s writing has a sweetness and savagery that knocks you sideways. In his latest drama – directed by Rachel O’Riordan, his collaborator on Killology and the shattering Iphigenia in Splott – he’s back among the streets and homes of working-class Cardiff, chasing down diamond-bright beauty and incandescent rage among the overlooked and undervalued.

The play’s relationship to Romeo and Juliet is very tangential, but if this isn’t Shakespeare, it’s packed with its own poetry, gorgeous as a shimmer of iridescent oil in dirty gutter water. And O’Riordan’s production – lean, unsparing, fizzing with feeling – hits us dead-on in the heart.

Its first image – a cheeky nod, perhaps, to Edward Bond’s infamous infanticide work Saved – is of a pram. But if there are horrors beneath the hood, they’re of a more routine variety: the baby is the daughter of teenage single dad Romeo (pronounced like the name of the car rather than Shakespeare’s tragic lover), and she’s just delivered a “poonami”. Romey (Callum Scott Howells) adores her; his alcoholic mum, Barb (Catrin Aaron), thinks everyone would be better off if she went to “the social”.

Julie (Rosie Sheehy), who’s determined to ace her A levels and study physics at Cambridge, meets father and daughter when they’re snatching a kip at a table in a library cafe. Before long, and in spite of herself – “I haven’t got a maternal bone in my body” – she’s fallen in love with them both, and is pregnant with a child of her own. She insists it doesn’t mean the end of her career dreams. But her pragmatic steelworker dad Col (Paul Brennen) and social carer stepmum Kath (Anita Reynolds) are damningly pessimistic, and soon the young couple face an agonising choice.

Continues...

“It’s too much” is an expression that recurs in Owen’s vibrant, rhythmic, saltily witty dialogue, among these people whose lives are stretched too thin over too much stress, too much exhaustion, too much making-do, too little money. They almost kill each other with kindness or with love, torn up by the tension between what they want and what they need: for themselves, and for their families.

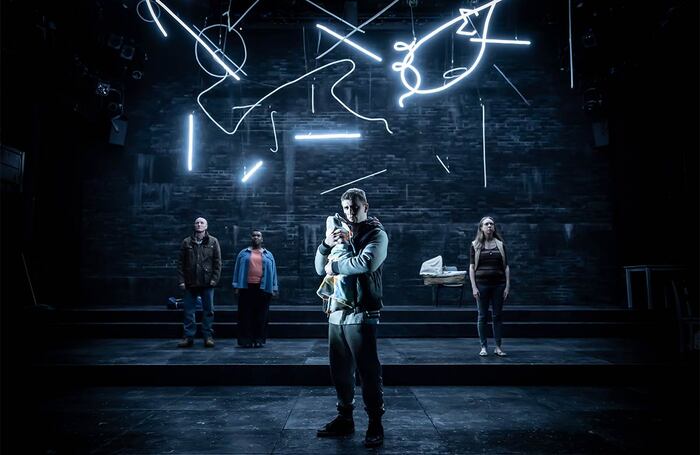

Julie’s passion for the infinite mysteries of the cosmos is brought hurtling down to earth by the minutiae of day-to-day survival, a contrast emphasised by Hayley Grindle’s design and Jack Knowles’ lighting, with squiggling neon constellations hung over a starkly utilitarian arrangement of featureless furniture.

O’Riordan directs briskly but with immense compassion, and the acting is faultless: Sheehy’s hungry, tough-talking Julie, as clever as she is naive, and Howells’ shambling but sensitive Romey are devastatingly poignant; so, too, are Aaron’s Barb – a destructive, desolately funny, raddled survivor – and Brennen and Reynolds, their parenting snarled up in their terror of yet more cruel disappointment.

This is, though, also a play full of hope, even joy: a modern subversion of a romantic tragedy that writes its own rules and finds not just a different ending, but new beginnings.

More Reviews

Recommended for you

More Reviews

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £5.99