Pijin | Pigeon review

Bilingual tale of innocence lost

Alys Conran’s debut novel Pigeon, a visceral lament to damaged childhoods, stunned critics and audiences on its release, winning the Wales Book of the Year award as well as its audience-voted equivalent. Theatr Iolo and Theatr Genedlaethol Cymru’s bilingual dramatisation (Welsh and English captioned throughout) Pijin | Pigeon largely packs the same emotional punch as its source material.

Bethan Marlow’s script evokes the craggy poetry of Conran’s text, small details painted on a massive slate-grey sky: the title character describes the lightness of an empty Tango can, while the dark mountain is like a giant reaching with its hands towards him.

Director Lee Lyford guides a fine, mainly very young, ensemble. Pijin (Owen Alun) knocks about with Iola (Elin Gruffydd), decent-hearted tearaways with storytellers’ souls, killing time in their North Wales quarry village. Pijin is supremely bright, though you imagine no one of note has noticed: his buzz cut and chip-on-shoulder strut disguise a precocious intelligence.

Pijin’s arc from cheerful scally to borstal boy is catalysed by the presence of Him (Carwyn Jones) – a stepfather who has knocked all life out of Pijin’s mam (Lisa Jên Brown) and has condemned his stepson to sleeping in the shed outside. Jones plays Him as an omniscient demon, apposite in a world Pijin describes in fairytale prose.

Continues...

Alun’s portrayal of innocence lost is very affecting, an accident then a murder propelling him towards the caricature his tough-guy demeanour suggests. Iola is the heart of the story: willingly led astray by Pijin but also his protector, she is wracked with a quiet guilt that’s skilfully played by Gruffydd. Nia Gandhi is endearing as Cher, the daughter of Him. She’s taken Pijin’s bedroom and is hated at first by the others. We realise she’s damaged too, in more ways than are obvious, and her unflinching optimism is as tragic as Pijin’s lost youth.

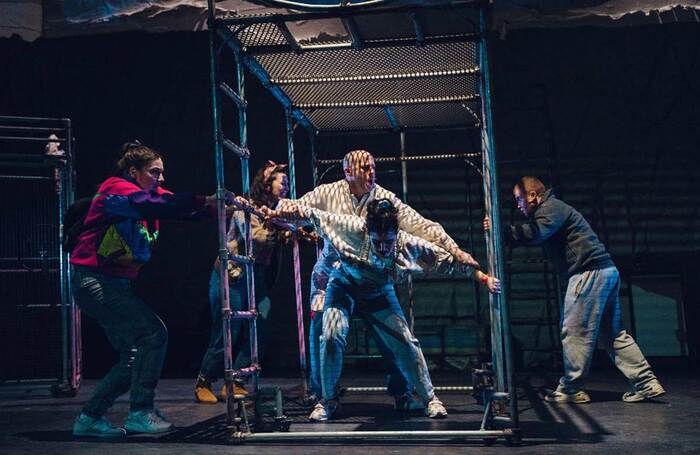

The production’s fussy design falls somewhere between minimalism and epic naturalism, sadly committing to neither. The stage is somehow sparse but cluttered all at once. Short punchy scenes are punctuated by overlong changes and the moving of countless props and apparatus, meaning the 100 minutes feels slower than it should.

Similarly, the action is caught between two stools – lurching from very literal combat scenes to stylised capoeira evocations of movement – meaning the production loses clarity at times. A key moment in which one of the main characters is badly injured feels vague, and took me out of the play at a key juncture.

Thankfully, the spirit and decency at the heart of the book shines through. Pijin | Pigeon is all the better when there are few tricks, and, as was Conran’s intention, the voices of the young people are properly heard.

More Reviews

Recommended for you

More Reviews

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £5.99