Ma Rainey's Black Bottom

The redemptive power of blues music lies at the heart of Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, August Wilson’s extraordinarily detailed and dramatically thrilling 1984 play. It’s part of his astonishing ten-play cycle that provides a portrait of the black American experience across the 20th century, with a play set in each decade.

All originally premiered between 1982 and his early death, aged just 60, in 2005, and only Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom is set outside Pittsburgh. Here we are in a 1927 recording studio in Chicago, where the fierce and formidable Ma Rainey – the self-styled Mother of the Blues – has come to lay a few tracks with her musicians, her girlfriend and stammering nephew whom she wants to record the introduction to a song, while her nervous white manager tries to keep the peace with the record studio owner.

Plot isn’t the main point with Wilson though; it’s merely a resonant background onto which to layer a superbly orchestrated and vividly realised set of characters, and the conflicts they have with each other, their histories and the exploitation of their talents.

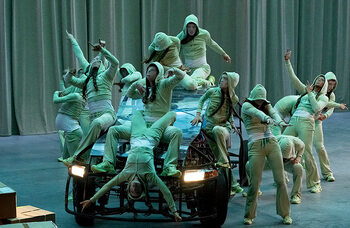

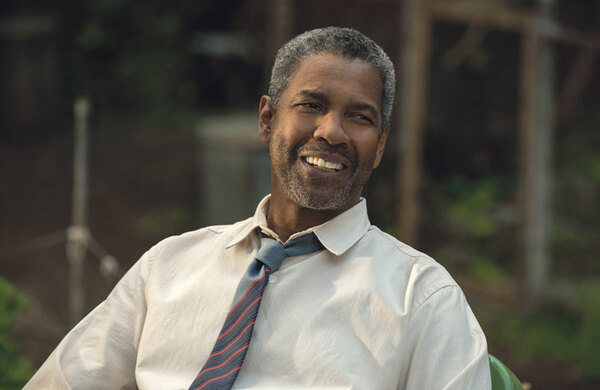

This play naturally (and inevitably, given its setting) uses music intricately and intimately to bring those themes and tensions to the fore, and the powerhouse delivery of Sharon D Clarke in the central role of Ma Rainey is exhilarating. “The blues help you get out of bed in the morning,” she says. “You get up knowing you ain’t alone. There’s something else in the world… This is an empty world without the blues. I take that emptiness and try to fill it with something.”

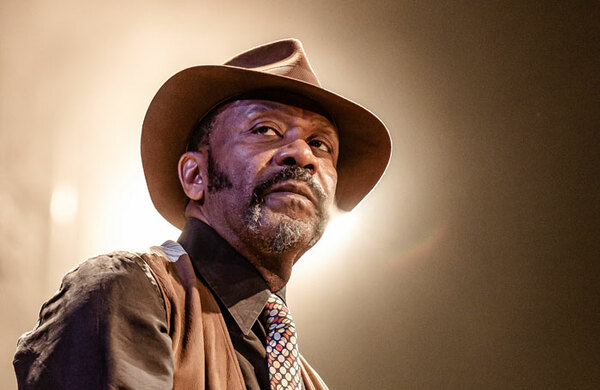

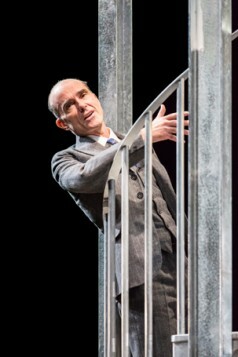

But Wilson’s sometimes painful and anguished play proves it comes at a cost – and she and her troupe of musicians are paying a high price (but not necessarily being paid one). Clarke is joined by a no less remarkable ensemble of Clint Dyer, Giles Terrera, OT Fagbenle and Lucian Msamati as those musicians, who divide seamlessly between those who are playing the instruments live and those who are not (credit to sound designer Paul Arditti for making the joins all but invisible).

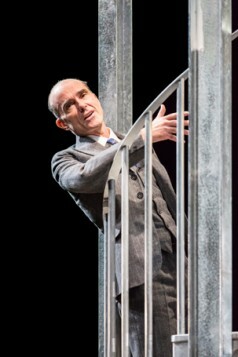

Equally brilliant in support are Finbar Lynch as her manager, Stuart McQuarrie as the studio owner, Tunji Lucas as Ma’s nephew and recent RADA graduate Tamara Lawrance as Ma’s girlfriend. The ensemble quality of the acting is keenly felt and their generosity to each other beautiful to watch.

I wish I could say that designer Ultz’s sets are similarly pleasing to look at, but the industrial — rather than industrious – studio setting is made up of a metal crate for the sound booth, suspended by chain cables, with a clunky reveal of the band’s downstairs rehearsal rooms that keeps coming up from below the stage, which threatens to dissipate the show’s continuity at times. It’s a minor glitch in an otherwise fantastic production.

More Reviews

Recommended for you

More about this person

More about this organisation

More Reviews

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99