Long Day's Journey Into Night

In his production of Eugene O’Neill’s 1956 magnum opus, which started life at Bristol Old Vic in 2016, Richard Eyre shows how completely a thundering script, carefully directed, with a couple of mighty actors acting hard, can sweep you off your feet.

Inspired by events in O’Neill’s own life and laced with the grief of all the losses he suffered, the play looks at the scarred lives of the Tyrone family. The mother is a morphine addict, the father a failed actor, one son a drunk, the other a consumptive. Slowly – very slowly – we watch these four disintegrate across the course of one long day, almost in real time.

It’s a glacier of a play, a monument of terrible force bearing down upon a tragic conclusion, but incredibly slow in its progress. That cold enormity is enhanced by Rob Howell’s glacial set, the transparent walls of this huge living room cerulean, almost neon, like light through ice.

Eyre’s production is carried, without a doubt, by the immensity of Lesley Manville’s performance. She spends the play morphing from lucid to delusional, in one moment she could be 50 and the next 90. She’s all jitters and forced smiles that fade in an instant, and when she’s on stage she barely stops for breath as if afraid that silence will force her to confront her addiction. There’s something about her performance that’s like watching your own mother disintegrate into the parts of her sum.

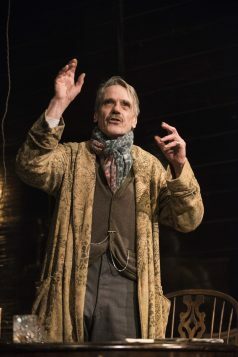

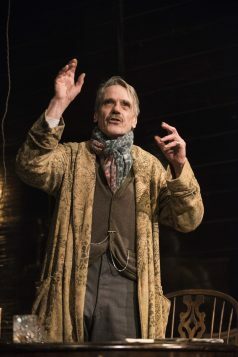

As James, a once-great actor frightened of being poor, Jeremy Irons is such a watchable performer, hamming it up ever so slightly, but capable of devastating moments of quiet. When James realises that Mary’s back on the morphine, he just clams up. He’s resigned, disappointed, tolerant, and it’s so sad. Rory Keenan as son Jamie is particularly good when he’s playing drunk, stumbling and swaggering, his face crumpled and ruddy.

Eyre leaves room in his direction for a random cough from consumptive Edmund, or for one character to overlap lines with another, to give the feeling of a real family conversation, and although there are moments of warmth and small ceasefires in the mud-slinging, he creates the photo negative of a happy family.

There are shortcomings, certainly: a strange misstep in the character of Kathleen, an Irish maid, played by Jessica Regan giving her best Mrs Doyle impression. As amusing as it is, it’s out of sync with the rest of the production. Matthew Beard’s performance as Edmund is a little contrived, as he lingers on unexpected syllables and moves in a lanky, slightly alien way. Also, Irons only remembers he’s supposed to have an American accent about four times in three and a half hours.

But this great Manichean struggle between virtue and vice won O’Neill his fifth (posthumous) Pulitzer Prize, and Eyre’s production makes it easy to see why. It’s long, the tragedy is inexorable, but with Manville and Irons on stage there’s a strange, tense satisfaction in watching it all unfold.

Lesley Manville: ‘I often feel guilty about how good things are in my career’

More Reviews

Recommended for you

More about this person

More about this organisation

More Reviews

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99