Sweep away the desperate and derelict controversy that’s frothed around its broadcast, and this TV adaptation of Mike Bartlett’s 2014 future-history play King Charles III is a delightful anachronism – a play for today.

Transplanted from the Almeida Theatre stage to BBC2 with the minimum of fuss, the scope for exteriors, cut-aways, close-ups and quick-cuts is sparingly exploited in a production that cosies close to the text, and to the performers who made it sing.

It’s not quite as simple as that, of course, and despite director Rupert Goold’s scruples with his original production, there are inevitable alterations, both gains and losses, that have occurred in the translation. Many are contextual – the effect of a soliloquy delivered to an audience is startlingly different to a monologue delivered straight to camera. One could be an airy reflection, a confidence, an aside; the other is conspiratorial by definition, all ambiguity collapsed.

It’s mostly the to-camera monologues that summon the shadow of House of Cards, and specifically the second part of the Ian Richardson version To Play the King, with its dense Shakespearean overtones, to tower over this not-dissimilar story of a monarch who oversteps his ceremonial bounds.

The other oddity in this new setting is the language and meter. What felt ingenious on stage occasionally clunks on screen, and while some of the strangeness fades as the gallop of Bartlett’s story-telling takes off, it still feels hazardously close to the kind of fakespeare gimmickery that the original production side-stepped, verbal reversals that rang ingenious onstage often feel obtuse onscreen.

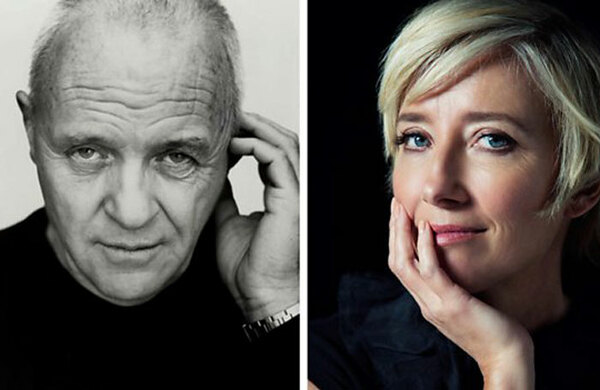

There’s plenty that’s good here, including the 11th hour capturing of Tim Pigott-Smith’s career-best performance as the beleaguered monarch. Frailer now, or perhaps just frailer in close-up, his shifts from bewilderment to iron resolve, his half-fatherly half-vengeful stare are as powerful as anything on telly, stage or elsewhere.

Despite all the politicking, it is family that breaks Charlie, it is the personal. His fall is seen in tiny, massive gestures, in his stance, his bearing.

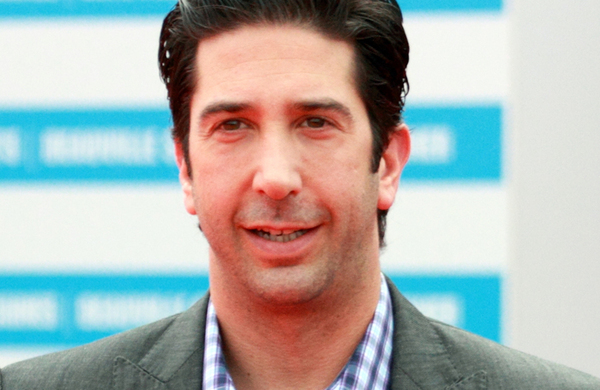

Elsewhere the cast find mixed success, returning Richard Goulding’s Harry is lumbered with the ‘prince among the paupers’ side-plot that felt mischievous fun onstage but just an unlikely contrivance onscreen, Oliver Chris is still superb as the hapless William, and newcomer Charlotte Riley is even harsher than her stage counterpart Lydia Wilson, as ruthlessly scheming Kate.

It remains a cracking story, Bartlett’s plotting a pure pleasure, his satire stiletto-sharp. Pigott-Smith holds the screen, utterly, as he did the stage, and Goold has done a double service in bronze-casting that performance for future generations, and building a rare and encouraging bridge between the telly-box and some of the country’s best and brightest new stage writing.

Maggie Brown: Charles III is Tim Pigott-Smith’s powerful swansong

More Reviews

More about this organisation

More Reviews

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99