Invisible review

Nikhil Parmar’s one-man play is funny and charming, but feels like a missed opportunity

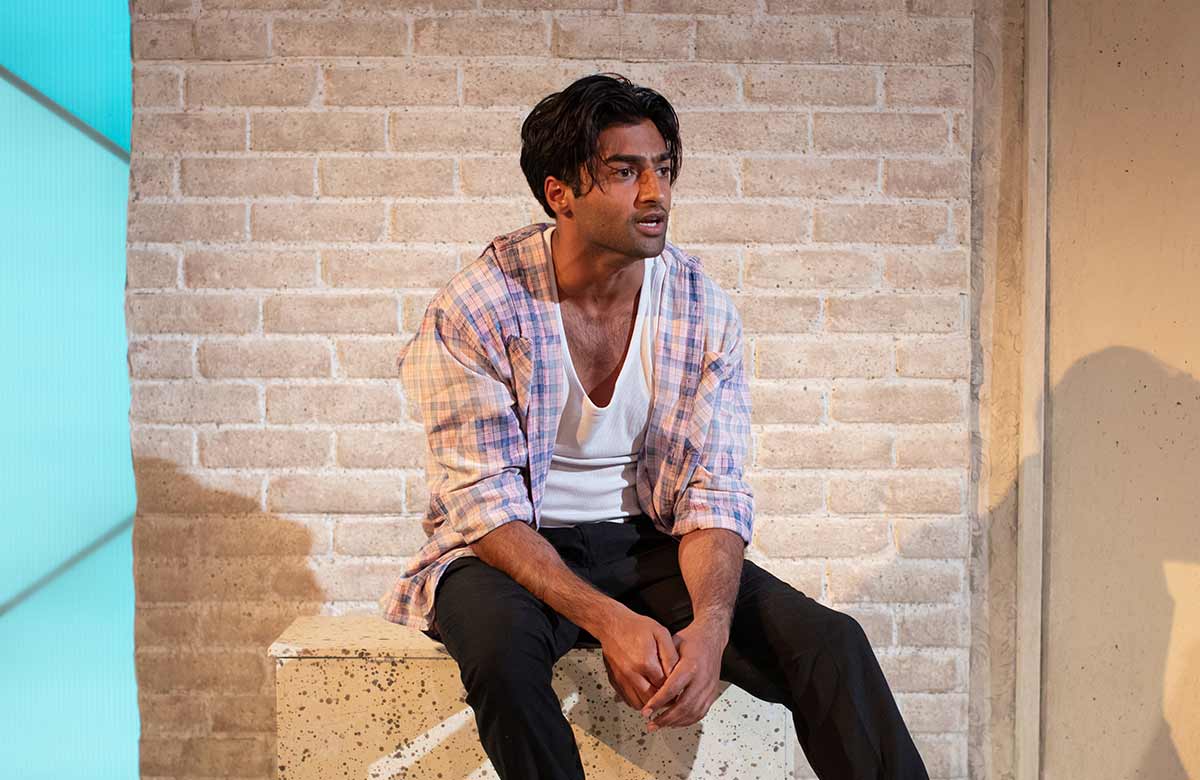

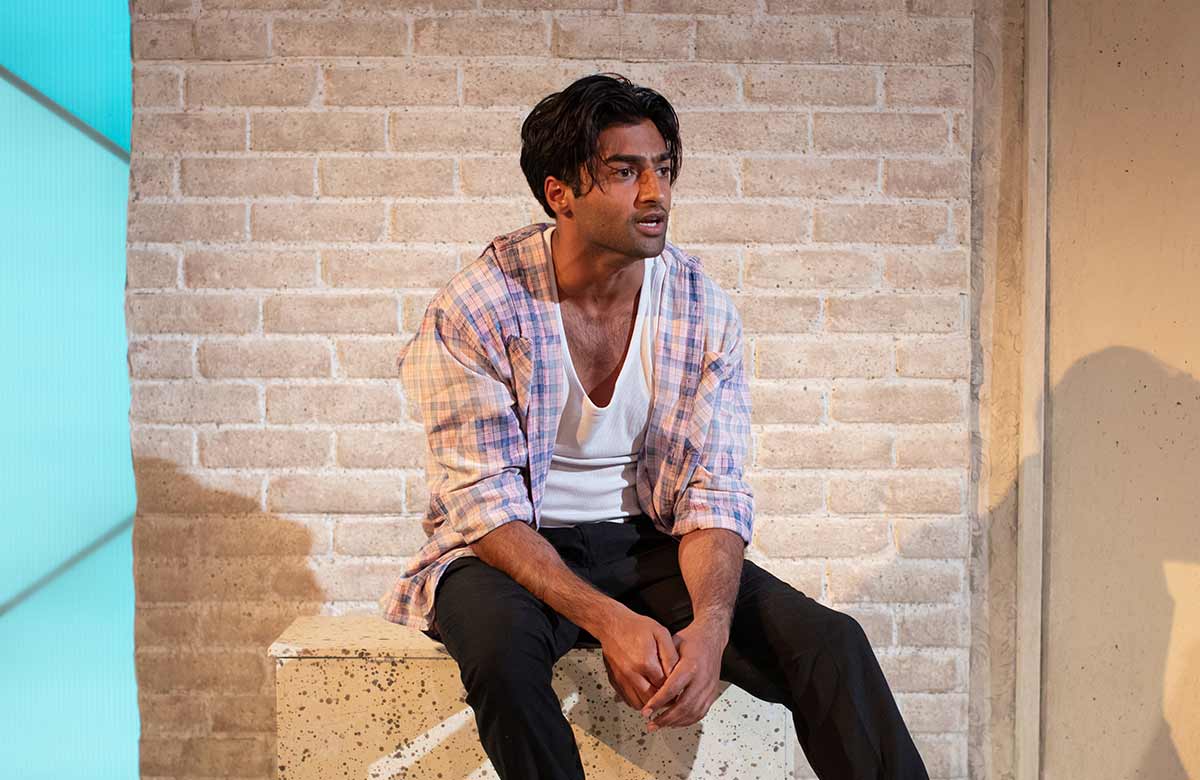

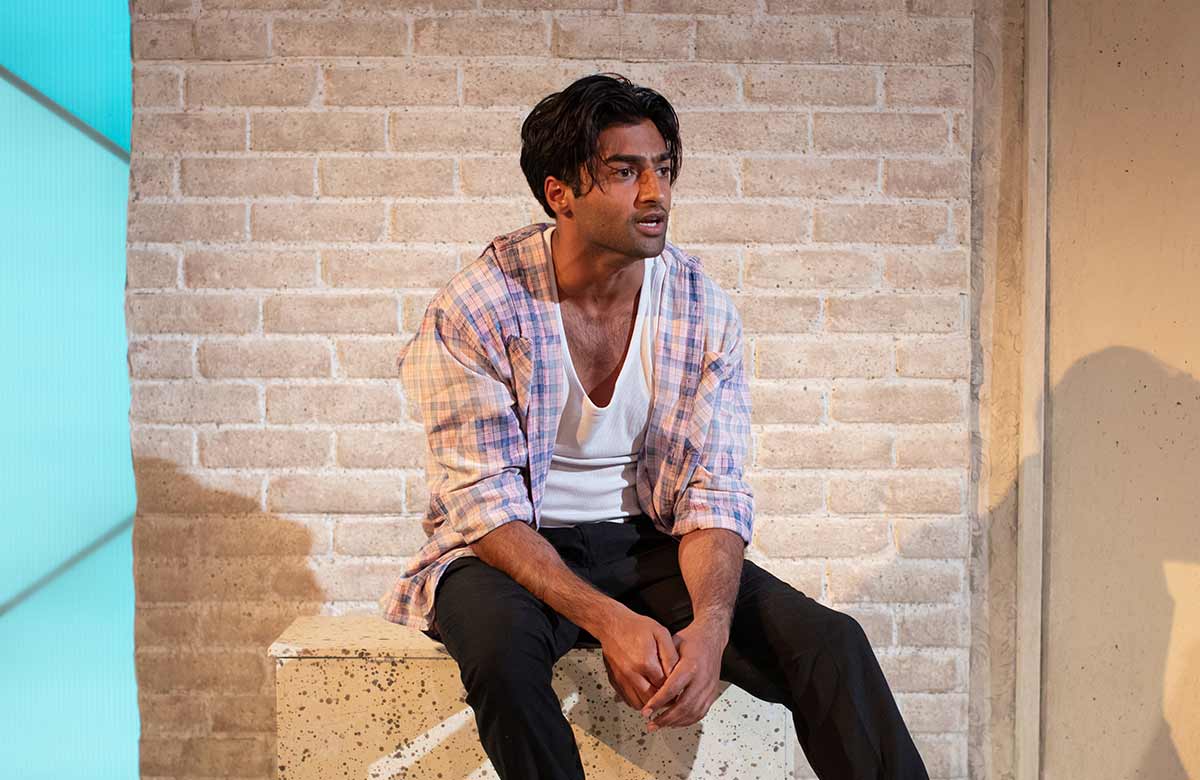

As a vehicle for Nikhil Parmar’s acting talent, this show nails it. Parmar the actor does pathos, humour and different accents – he plays women, he plays men; he goes from Bond to Bond villain, and he even punches himself in the face and falls over. He can do it all.

So why has Hollywood not come calling?

The narrative of Invisible details why Parmar and other actors of colour shouldn’t be typecast into reductionist roles, as told by the semi-autobiographical character of Zayan. Zayan is a self-absorbed, out-of-work actor and part-time weed dealer who is an unfit parent to his one-and-a-half-year-old daughter Sienna.

The plot is a loose jangle that follows Zayan through his life, as he hangs out with his waster cousins and conservative parents and endures confrontations with his ex’s new boyfriend – a rival from RADA whose career is faring much better than his. Zayan often breaks the fourth wall to comment on the action in amusing asides.

Parmar, the writer, was previously a member of the Bush Theatre’s Emerging Writers Group, and his other credits include My White Best Friend – North at the Manchester Royal Exchange. But in Invisible, Parmar’s skills as an actor outstrip his skills as a writer – the tropes of the one-person show are box-checked without adding much to the story.

Zayan’s character is charming and sympathetic despite his loser status, but his climactic final act seems to come from nowhere, and a loose emotional connection that could explain why he’s neglecting his daughter is under-explored.

The script shines when it’s funny and surreal: Zayan is most famous for doing a commercial for "Frank’s Funky Fried Chicken" – with accompanying dance moves – and his money is "currently tied up in... Oyster cards".

Laura Howard’s pastel lighting adds subtle moods to emphasise Zayan’s emotional life, while the set of corrugated plastic and bricks by Georgia Wilmot evokes his outsider status.

Yet the point about being "invisible" doesn’t seem intrinsic to the story. Zayan failed a few auditions – so what? That’s the acting life.

There was maybe a braver and more controversial point to be made here about how diverse casting still has a way to go. A tokenistic move to cast one or two black actors is not enough – true diversity might mean fewer white actors and more of everyone else. But the play skirts around this issue and feels like a missed opportunity to make a more powerful point about today’s entertainment industry.

More Reviews

Recommended for you

More about this organisation

More Reviews

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99