Death of a Salesman

This production was reviewed in Stratford-upon-Avon. It has since transferred to the West End’s Noel Coward Theatre, where it plays until July 18, 2015. Press night was May 13, 2015

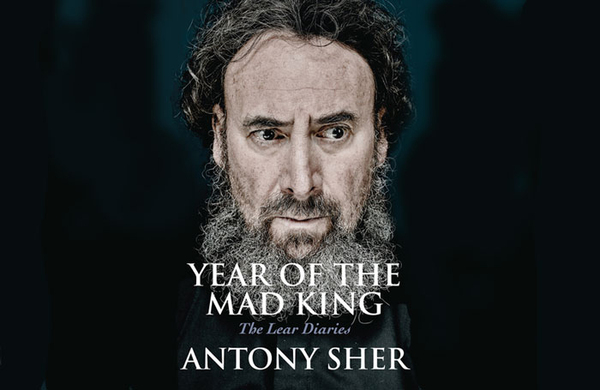

For Antony Sher – who recently played Falstaff in Gregory Doran’s Henry IV for the Royal Shakespeare Company and will be returning next year to play Lear – this is part of a loose trilogy of roaring roles: men who dream, men who rage.

Doran’s production of Arthur Miller’s play opens the RSC’s summer season and also marks the first time that a play by an author other than Shakespeare will fill the company’s ‘birthday play’ slot.

Sher sinks into the role of Willy Loman without wallowing in it. He’s alternatively absurd – puffed up, volatile and oddly frog-like, all bluster and bark – and a figure of pity, a man uneasy in his own skin. His sense of self is clearly slipping, and Sher conveys a sense that Loman is not fully in control of all he is saying. At times it’s as if his words are leaking from him; he speaks in a kind of corrugated warble that occasionally grows into a bellow.

Harriet Walter, as Willy’s weary but watchful wife Linda, is more restrained, but her love for her husband is always there – a constant, an anchor.

Alex Hassell, who recently played a charismatic Prince Hal to Sher’s Falstaff, builds on their existing relationship to good effect. His performance as Loman’s son Biff, who has all his father’s hopes riding on his shoulders, is perhaps the most aggressively transformative – one minute a gleaming golden boy, the next a shell of the man, struggling to be something he isn’t. He seems to visibly shrink and pale as the production progresses.

Doran has said in recent interviews that he believes Death of a Salesman to be the greatest of American plays, as potent and long-reaching as the work of Shakespeare. His trust of and respect for the material is evident. It is perhaps even a hindrance at times, for the production feels a little timid at the beginning and takes a while to gather momentum. But gradually the pace builds and the second half contains scenes of excruciating pathos as the things to which Loman clings are stripped away. The moment in which Loman looks on uncomprehendingly as his son breaks and weeps is painful to watch.

Stephen Brimson Lewis’ set is similarly shifting. The Lomans’ house is surrounded by zig-zagging New York fire escapes, creating a frame for their dream-dancing. As the play slides back and forth in time, Tim Mitchell’s lighting greens the Brooklyn brick; there are moments when the backdrop of apartment blocks is reduced to a collection of outlines, like something designed by Saul Bass, before the reality of the characters’ world reasserts itself. The city is changing, America is changing, but it’s part of Loman’s tragedy that he cannot change with it.

More Reviews

Recommended for you

More about this person

More about this organisation

Summer spectacle: opening this week in previous years

More Reviews

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99