The Prince of Egypt at the Dominion Theatre, London – review round-up

Animated film to blockbuster musical: it’s a well-established route to stage success, one previously trodden by Frozen, Aladdin, and, most famously, The Lion King. Now, a new West End show is following in their footsteps – The Prince of Egypt is based on the 1998 Dreamworks film based on the book of Exodus, and opens at the Dominion after tryouts in California and Denmark.

The original film is not as iconic as some of its Disney rivals, but it was a soar-away success nonetheless, earning $218 million at the box office to become the highest-grossing non-Disney animation ever at the time. The songs by Wicked-composer Steven Schwartz were nominated for an Oscar, with When You Believe winning the award for best original song.

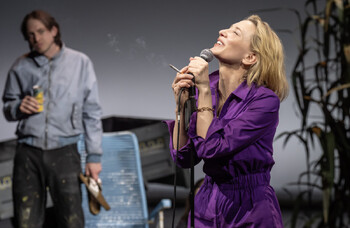

This stage version – booking until October – has a few new songs by Schwartz, and is directed by his son Scott, with a book from prolific screenwriter Philip LaZebnik, design from Kevin Depinet, and choreography from Sean Cheesman. The enormous ensemble features Luke Brady as Moses, and Liam Tamne as Ramses.

But is this latest Bible-based, Broadway-bound screen-to-stage adaptation praised by the critics? Do Schwartz and his son supply another wicked addition to the West End? Or will there be audience exoduses galore?

Fergus Morgan rounds up the reviews

The Prince of Egypt – A Biblical bore

Like Joseph and the Amazing Technicolour Dreamcoat and Jesus Christ Superstar before it, The Prince of Egypt takes a biblical story and turns it into a stage show. It’s a familiar fable: Moses, cast adrift on the Nile, adopted by Egyptian royalty, eventually leads the Hebrews to freedom, via 10 plagues and the parting of the Red Sea.

A tale as old as time, but one that’s retold again here in simple, straightforward fashion. “Those hoping for a revisionist spin a la Wicked take note: this is Exodus, delivered with Sunday-school seriousness,” warns Dominic Cavendish (Telegraph ★★★). And the result, according to most critics, is a show that dawdles dramatically.

LaZebnik’s book “plods from one incident to another with little character or much narrative development”, leaving its protagonists in a “dramatic wasteland” according to Mark Shenton (LondonTheatre ★★). The dialogue, adds Clive Davis (Times ★★), “veers from cheeky-chappy to chest-thrusting” and sets off “unintended laughter” in the audience, according to John Nathan (Metro ★★).

“Subtlety and nuance are eschewed in favour of melodramatic bluntness,” agrees Alex Wood (WhatsOnStage ★★★★), while Marianka Swain (TheArtsDesk ★★★) thinks the whole thing “prosaic” and David Benedict (Variety) reckons it’s “clunky”. Alice Saville (TimeOut ★★★) isn’t the only one who finds the wafer-thin female characters’ depiction “disappointingly retro”.

“It’s too dark and solemn for families, too dim-witted for adults,” concludes Nick Curtis (Evening Standard ★). “When it comes to Old Testament singalongs, I’ll take the breezy, ditzy Joseph over this tedious Moses any day.”

The Prince of Egypt – Stunned into submission

The Dominion stage has previously hosted some huge shows – We Will Rock You, An American in Paris, Bat Out of Hell. The Prince of Egypt is no different and that, for a few critics, is part of the problem: the show’s spectacular staging swamps out its story.

“We’re meant to be in the vast halls of the Pharoah’s palace one moment, an endless desert the next, constantly shifting scales and locations,” describes Tim Bano (The Stage ★★★). “The show relies a lot on projections, beautifully rendered pharaoh heads and hieroglyphs by Jon Driscoll, and there are some amazingly colourful costumes from Ann Hould-Ward, but they don’t quite mesh with the physical set, which has the slightly artificial quality of a theme park.”

“It is so excessive and outsized that it overwhelms the emotional drama, sucking away any intimacy between the actors,” writes Arifa Akbar (Guardian ★★), while for Cavendish, this “cinematic” approach “reaps mixed dividends”.

For the majority of reviewers, though, Scott Schwartz’s staging is stunning enough to succeed. “This production is far more about the blockbuster exterior than the inner life and, suiting the cavernous Dominion, it generally delivers on that score,” contends Swain. “Schwartz knows his way around a mammoth set-piece, whether a buoyant celebratory dance, rain of fire, or the much-anticipated parting of the Red Sea.”

One thing almost everyone agrees on is the quality of the movement. The show is “at its strongest as a dance production with beautiful visual formations through bodywork when chariots, wells or rolling desert sands are created by groups of dances,” asserts Akbar. “It is in Sean Cheesman’s astonishing choreography that this musical feels most alive.”

It’s “simply divine” agrees Wood. And although “there are some odd decisions”, if you “give yourself over to the production and let it take you on its merry way, it’s hard not to get swept up in the overblown theatricality of everything on offer”.

The Prince of Egypt – Adding to the originals

Schwartz senior’s career in stage and screen has spanned nearly five decades and seen him pick up three Academy Awards, three Grammy Awards, and six Tony nominations. Alongside 1971’s Godspell and 1972’s Pippin, his best-known musical is Wicked, written three decades later in 2003. For The Prince of Egypt, he has added 10 more songs to the film’s slim score.

The general critical consensus is that the old songs are the best, with the new additions dismissed as “ponderous” by Curtis, “unmemorable” by Wood, and “drowned out by the scale of everything else by Akbar”. It’s only Bano that admires the additions, finding it “fascinating” and lauding its “slippery shifting effect”.

Those original numbers, though – When You Believe and Deliver Us in particular – still strike a chord. They supply a “surge of hair-raising joy and brim”, writes Wood, who calls musical director Dave Rose’s orchestration “awe-inspiring” and adds that “it was heartwarming to see dozens of punters walking down and watching the orchestra after the curtain call”.

And what of the cast themselves? Emerging actor Luke Brady plays the central role of Moses and although several critics point out the slimness of the part, most praise his commitment nonetheless. He is “natural and likeable” for Bano, supplies a “David Essexy twinkle” for Cavendish, and “holds the show together with near-Herculean power” according to Wood.

Opposite him, Tamne has a longer list of West End credits, from Phantom of the Opera to Wicked. Again, he does well with what little he has to work with, Wood praising his “multi-faceted take on the tortured and conflicted Ramses, and Saville impressed by his “convincing mercurial streak”.

The Prince of Egypt – Is it any good?

Um, no, not really. The choreography is class and the original songs and staging are spectacular enough to convince some critics, but most find the underwritten roles and cripplingly clunky dialogue too much to take.

A four-star rating from Alex Wood on WhatsOnStage is an optimistic outlier, but most critics opt for two or three stars, with Nick Curtis supplying a particularly painful one-star review in the Evening Standard. Avoid it like the plague is his advice.

But then, critics said the same of another animation turned stage-show more than 20 years ago, and The Lion King is still going strong at the Lyceum, so who knows? Maybe this Moses musical will prove a miraculous, critic-defying success after all.

Ann Hould-Ward: ‘My dad was a dry-land farmer, he taught me to work real hard’