Lenny Henry in The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui, Donmar Warehouse, London – review round-up

There are no prizes for spotting the thinking behind the Donmar Warehouse’s staging of a fresh adaptation of Bertolt Brecht’s classic 1941 satire The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui, in light of recent political happenings across the Atlantic.

Simon Evans’ production, which uses a new text by Clybourne Park writer Bruce Norris and stars Lenny Henry as the eponymous power-hungry Chicago racketeer, runs until mid-June. Whether or not it makes it that far might depend upon the nuclear trigger-happiness of the very figure it seeks to lampoon – the current resident of 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue.

Arturo Ui’s last major London outing was only four years ago, when Jonathan Church’s acclaimed Chichester production transferred to the West End, with its lead Henry Goodman and a clutch of four-star reviews in tow. But a fair amount has happened since then.

Does Evans’ production shed light on the transatlantic turmoil of the past couple of years, or does it lose itself in a sea of lampoonery? Does Henry help make the Donmar Warehouse great again, or does he lose bigly? Is it fake news or do its alternative facts hit the spot? Fergus Morgan rounds up the reviews…

The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui – sledgehammer satire

In 1941, Arturo Ui was an extremely thinly veiled stand-in for Hitler. In 2017 – no spoiler alert – Norris’ adaptation sets its sights on Donald Trump instead, with nods towards wall-building, overestimation of crowd sizes, and making stuff great again crammed in. But does this refocusing pay off? Not quite, seems the critics’ response.

Some take against the contemporary conceit for its blunt approach. It is, says Andrzej Lukowski (Time Out, ★★★), “so on-the-nose it basically punches you in the face shouting TRUMP IS LIKE HITLER!!! TRUMP IS LIKE HITLER!!!”

Natasha Tripney (The Stage, ★★★) agrees, finding Evans’ production “heavy-handed in the way it insists on the play’s contemporary parallels” and all the modern-day references “clunky”. For Nick Wells (Radio Times, ★★★) meanwhile, the constant allusions “sail a little too close to pantomime”.

“It’s almost exactly what you’d expect and that obviousness makes it seem rather toothless,” Matt Trueman (WhatsOnStage, ★★★) contends. “Where lampooning Hitler in 1941 was a weapon in itself, Trump’s rather impervious to the approach. He’s already a joke, and, leaving aside the horse having bolted, the show struggles to reconcile the laughing stock loon with the very real danger.”

Others don’t think that the Ui/Hitler/Trump analogy really works for more logistical reasons. “At numerous points, the comparison with Trump breaks down,” writes Michael Billington (the Guardian, ★★★). “Where Arturo brutally dispatches his enemies, Trump has bred an active opposition,” he cites, by way of an example.

Paul Taylor (Independent, ★★★★) goes further. “The Third Reich parallels don’t feel to me to cooperate as drama with the persistent references to Trump,” he admits, concluding that Norris’ Trumpian allusions never “properly enter the bloodstream of the play”.

Some critics notice a danger here, too. Dominic Cavendish (Telegraph, ★★★★) observes that this “over-hasty” reading “lets blatant autocrats like Putin, Assad and Erdogan, and for that matter Mugabe and Zuma, off the hook”, and Ian Shuttleworth (Financial Times, ★★★★) argues that it “may have the opposite effect from that intended” by “making the serious seem trivial”.

“Ultimately The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui is a fairly specific allegory for Hitler’s rise,” writes Lukowski, who speaks for most when he asserts that this revival “doesn’t really have anything beyond the very superficial to say about Trump.”

The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui – prohibition politics

Brecht reset his parable about the rise of Hitler in 1930s, mobster-ridden Chicago, recasting Hitler as Ui, and the senior figures of Nazi Germany as Ui’s gangster henchmen. Evans realises this relocation by reimagining the Donmar auditorium entirely.

“The stage has been transformed for the occasion into a Chicago speakeasy in 1931,” describes Ann Treneman (the Times, ★★), “with tables and (very uncomfortable) chairs ranged around the edges.”

And there’s a fair amount of audience participation too. “Evans folds the audience into the mix, pulling volunteers on stage as objectors, then bumping them off,” writes Trueman; “Sit at the front and there’s a chance you might be asked to carry the can (quite literally) for the characters,” warns Tripney.

For some critics, this conceit is a powerful one, Charlotte Valori (TheatreCat, ★★★★) labelling it “entirely apt” and Eleanor Turney (Exeunt) explaining how it “builds a clever air of complicity between gang and audience”.

For others, though, it’s fun but gets in the way; “A stilted play at the best of times, Arturo Ui needs all the momentum it can muster,” explains Trueman. “Our involvement – and our embarrassment – makes it stall.”

According to Billington, Evans “overdoes” the audience involvement. “We laugh merrily at seeing our neighbours hauled on stage to play a corpse or a harassed trial-defendant,” he notes, “rather than coolly assessing, as we should, the links between political extremism and economic decline.”

It’s only at the end, when the audience is asked to stand up to show support for Ui, and the few that don’t are humiliated, that the emphasis on spectator involvement makes sense to most. “Evans’ point is that politics is all theatre,” writes Trueman, “and we willingly play along.”

“If we don’t actively object, we are complicit” spells out Marianka Swain (the Arts Desk, ★★★).

The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui – Arturo Ui, national treasure

So the contemporary parallels feel a little stretched, and the audience involvement is hit and miss. What about our very own demagogue – Lenny Henry’s Arturo Ui?

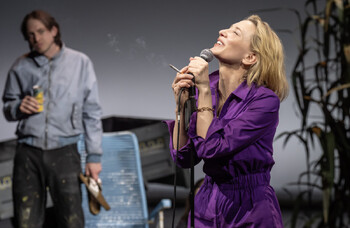

He delivers, that’s for sure. His performance is “explosively good” according to Treneman, “an absolute powerhouse” according to Chris Selman (Gay Times, ★★★★), and “another casual tour de force that showcases his irresistible combination of talents” according to Cavendish.

“Others have played him as a shabby loser, a furtive sewer rat or a clownish, creepy counterpart of Shakespeare’s Richard III,” writes Henry Hitchings (Evening Standard, ★★★★), “but Henry makes him a smug bully with an intimidating physicality and a bruising smile.”

“The erstwhile comic plays Ui as a big, still, intimidating guy with a gluey Bronx accent,” adds Lukowski, “not trying to frantically steal scenes but instead offering a compelling, darkly zen core to them.”

Henry’s brilliance is matched by the entire ensemble; “There is great support from the whole cast,” writes Philip Fisher (British Theatre Guide), and his sentiments are echoed all round.

There’s particular praise for Michael Pennington’s Hindenburg parody, Dogsborough – “the right mix of venality and vulnerability” according to Billington and “the ghost of Bernie Sanders” according to Trueman – and for Lucy Ellinson’s Goring-inspired, gender-swapped Emanuele Giri, who’s “unnervingly impish” according to Tripney, and “chills the blood” according to Shuttleworth.

Tom Edden gets a lot of love for his hammed-up thesp, too – the man who instructs Ui to walk the walk and talk the talk. He is “scene-stealing” for Hitchings, the moment he accidentally teaches Ui to make a quasi-Nazi salute is “chilling” for Tripney.

The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui – is it any good?

It’s not subtle, if that’s what you mean. Norris’ text takes aim at the Donald over and over again, this scattergun approach getting laughs but not finding much favour with the critics, most of whom find it too inaccurate, too glib, or just too much.

It’s a similar story with Evans’ spritely production and it’s emphasis on audience involvement: it’s a lot of fun, by most accounts, but doesn’t really strike a chord until the show’s denouement, despite a stonking central performance from Henry and strong support from the ensemble.

Henry’s Arturo Ui might win the White House then, but Evans’ production doesn’t quite get the critics’ popular vote.

More about this person

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99