Tim Bano: Does The Encounter work as a live-stream?

Like Simon McBurney at the beginning of each performance of The Encounter, I took a photo of the audience to prove that I was really there.

So that’s me and my cat just before the live-stream started. I could take that photo because I wasn’t in a theatre. I wouldn’t dare whip out my camera in an actual theatre. Likewise if I kept checking Twitter, or turned house lights on and off, or made dinner, or went to the loo without shutting the door. It’s acceptable at home. It’s not acceptable in the theatre.

But that photo was actually taken this morning. I lied. Sorry. Because one of the biggest thrusts of the show is the sense of illusion: phones can hold more photos than our grandparents would have had taken of them in a lifetime. But those photos are not our lives – they are snapshots that form a story of our lives, like frames of a film. In the same way, we know that Simon McBurney in The Encounter is creating the world around us, but it is not actually the Amazon rainforest. It’s a theatre. And, here’s a new layer in the experiment, what I and thousands of other people watched this week wasn’t The Encounter. It was a recording of The Encounter. Just frames of a film.

When you’re watching the show in a theatre, McBurney strolls on and tells people to turn their phones off and then, before you know it, you realise the show actually started 10 minutes ago and he’s quietly hooked you into this narrative. But a live-stream necessarily has a beginning and an end, there’s no chance to build momentum, to deceive the audience. Once you transpose the show into any other medium than theatre, it demands a clear point of commencement.

There’s a noble sentiment in attempting to prolong the limited lifespan of such a phenomenal show, and to expose it to audiences much more widely than a run in a theatre, or even a nationwide tour, can achieve. But if the work of art is reduced, if it’s diluted from its original state, is it a) worth it and b) still the same work of art?

Undoubtedly, the live-stream adds something to the show – bigger audiences means more discussion, more engagement. But it also takes something away.

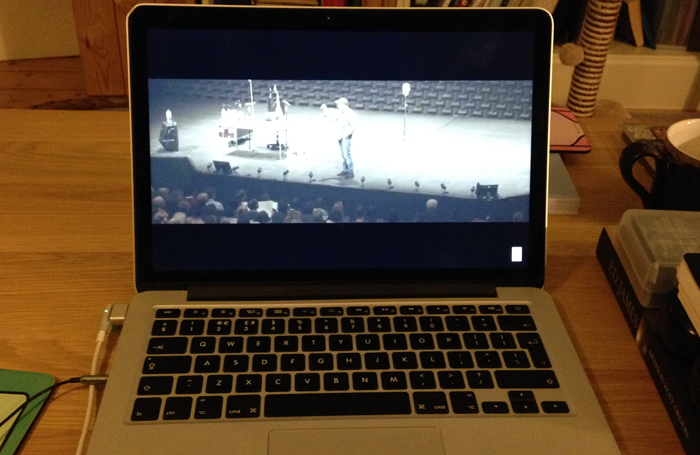

For one thing, the act of confining the show to a small laptop screen completely changes any sense of scale and context. In an auditorium, I can look anywhere I want around this huge black stage. I can absorb the detail of the anechoic wall in its huge splendour, or focus on McBurney’s blood-smeared belly. From my fixed point in the auditorium I can see him get bigger and smaller as he moves, incessantly, around this environment. That is important. In the live-stream we don’t get to choose where to look. Camera angles are chosen for us. A screen is an imposition, a limit, both a reduction of three dimensions into two and a shrinking of a vast stage into an 11 inch screen.

And where I choose to place that little screen plays a big part in my enjoyment of th

[buffering]

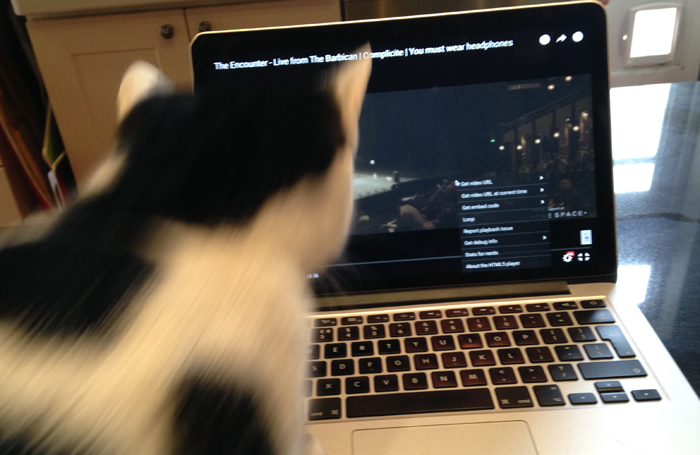

Sorry, my internet just cut out. What was I saying? Oh right: there’s a responsibility to create one’s own environment. In the Barbican that’s all done for you. There’s no other option. Get up and go to the loo if you want, but it’ll ruin it. At home you have to choose to be complicit, to turn your phone off, to put the video into fullscreen so that you don’t have to read the comments. Like ‘is he going to talk about his prostate’ from Chantal Simm. Or ‘HE WALKED ACROSS MY BRIAN’ from Jesse Cooper.

I create my own context, with none of the sense of occasion that comes with going to a theatre. Wine out of one’s own wine glass isn’t the same as the ceremony of sipping it from a plastic cup. Dinner on one’s knees removes any theatrical glamour.

Besides which, the Hawthorne Effect surely comes into play: McBurney is aware he’s being filmed, so how did that affect his performance yesterday evening? Watching something on stage, moments and fragments and impressions lodge in the memory but not much more. A recorded stream makes the temporary permanent and it is that performance that comes to be ‘the show’, the permanent record. No longer scattered across the memories of its audience members from every different performance, alive in a collective of minds, the recording makes it definitive and permanent.

It splits The Encounter into two versions: one that only exists, irretrievably, in the past (in the memories of its audience), and one that will always exist in the present (in its filmed, permanent form). This snapshot:

Is different from this snapshot:

That recording will never be live again. And the ubiquity of having things on demand has warped what ‘live’ actually means. I was actually watching the stream with a five minute delay, because I couldn’t find my headphones at 7.30pm. And it’s available for seven days to stream, which again isn’t live. Which makes all the difference: theatre is theatre because it’s happening right there, imbued with the frisson of danger, the possibility it could go wrong, and the desire it should go right.

But my reservations faded eventually. About an hour or so in, I settled. Suddenly, with the lights off and the comments shut out, it hooked me. In a different way from when I saw it in the theatre, true, but it absorbed me, assimilated me into its yawning world.

It’s not theatre, but nor is it television or radio or any category or medium we’ve invented. What it is, in fact, is a realisation: that mainstream filmed media haven’t even begun to understand how sound can complement image. It could be extraordinary – and, here, it is.

The Encounter is available to stream at www.complicite.org until March 8

Opinion

Recommended for you

More about this person

Advice

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99

Tim Bano

Tim Bano