Paule Constable: Forget the season announcement, the NT is a cultural leader at supporting women

The National Theatre has faced widespread criticism for the lack of women writers and directors in its upcoming season, but award-winning lighting designer Paule Constable says the organisation is at the forefront of giving women safe spaces to make their best work

I have been thinking a lot about the furore that has surrounded the National Theatre in recent weeks. And there is something worrying me.

True equality is about more than quotas. It’s about looking at how we all make work, about the hierarchy we work in and how we all behave towards each other.

National Theatre responds to playwrights’ letter criticising all-male programme announcement

I am proud to be different, proud to have a female voice. I think, see, feel and experience through a different lens. Ultimately, we are all striving for the freedom to find a voice – to develop it – to give it volume and strength. And where, in my long career, has this happened the most?

My love for lighting started because it was boysy. I was tomboy material – happiest climbing trees and beating the boys at their own games. I discovered lighting in the rock’n’roll world of the mid-1980s, when people worked hard and swore harder.

Having a woman around who wanted to do the same was unusual. I was something of a mascot: tolerated – even encouraged – because I was different… but never taken seriously. Not a voice – a joke.

And then I discovered theatre and the women who worked in it. Shifting to experimental theatre, with so many amazing women who were administrators, producers and makers – Glynis Henderson, Heather Ackroyd, Hilary Westlake, Melanie Pappenheim – I was amazed that they had voices. I started to feel stronger.

Moving into design, my own voice was quietly forming. It was there I met the women who changed my life: Rae Smith and Vicki Mortimer. Women who spoke as women, who shaped their work around their unique, female experience.

Read our interview with Vicki Mortimer

My voice was changing, becoming more profound perhaps – certainly more vulnerable – but also more open. And we, as artists, could really talk to each other and be less apologetic about being different.

I travelled the world. The women I had met fuelled me and allowed me to do battle. And it was just that – a battleground. Every new building and every new culture had a new set of assumptions. A new set of unwritten rules. The question was always how quickly could you learn those rules, draw up your own strategy and find a way through.

How do you get this wall of male expectation to dump its miserable assumptions and allow you to just do the job? Don’t be amazed or surprised that I am adequate at what I do – don’t start from that place. Always behind me were Vic, Rae and many others, giving me strength.

That is what every moment took. I don’t mean the strength needed to take creative risks, those everyday creative panics and fears – they alone would be fine. No, the strength to walk tall in a world where every room you enter has one question it wants to scream at you: “Can you or can’t you do it, because you are a woman?”

I dream of a world where the only question is: “Can you or can’t you do it?” That I can deal with. But the assumption that I can’t do something because of my gender – that I’m in the wrong room, the wrong trousers, the wrong job – is so thoroughly wearying.

My first experience of being in a building that felt different was at West Yorkshire Playhouse when it was run by Jude Kelly. Rae and I designed a Death of a Salesman there. A few days into rehearsals, I realised that I was slightly less tense, that Rae and I were wrestling with the show, but it was just that: a show. The currency of the building was different. Jude had created a culture in which the question of whether you were fit for purpose just wasn’t asked. I was invited to have a voice and the person in charge was giving me credibility and status. I began to talk more.

And now? I’m older, so I’m less apologetic and less frightened. I’ll push as hard as I have to. And there are many places where I still have to push hard. Outside the confines of the UK, you really start to see how advanced we are compared to many and how backward, compared to a few others.

I have recently worked in national opera houses where the sentiment that the nasty, shouty, demanding woman should let them get on with doing things their way was very apparent. But fuck it – I’m not going anywhere. The least I can do is a good job against the odds and let the work speak for itself.

I also realise that there are buildings where we can ask difficult questions and try to create a new balance. I worry that a pressure to tick boxes and fulfil quotas is putting wonderful young women artists into the limelight and pushing them into rooms where they are vulnerable. Especially because without changing the culture we make our work in, the environment isn’t supportive enough to nurture those young artists.

The answer? It isn’t simple. We have to nurture young talent, particularly women. We have to look to develop a more diverse workforce, where all the surrounding faces are not male and white. It may be more rare to walk into a rehearsal room like that now, but it isn’t unusual to walk into the backstage area and see it. That’s the world I am in – and the world I am trying to wrestle and encourage young, ethnically diverse women into. That change can’t happen overnight, nor can it happen quickly.

All of these thoughts surfaced recently because it occurred to me the National Theatre is one of the only buildings – alongside London’s Royal Court and the Young Vic – where I feel safe and where the dynamic of the backstage workforce is changing. Where they are asking questions about different working hours and practices. Where they are creating opportunities for people – beyond the usually accepted routes through drama schools – to come into the building as apprentices, as trainees and be given a voice and start their journey.

I hope they find the administrators and managers who might encourage them to see what is possible, and who give them safe spaces to find voices and to take risks. So while I can absolutely understand and hear the frustrations of the critics of the recent NT season announcement, I want to shout out in the other direction.

I want to say thank you to the NT and to the joint efforts of Rufus Norris and Lisa Burger for creating a safe space for young technicians, designers, makers, producers, production managers, programmers, electricians, automation experts, health and safety officers, fight directors, sound designers and operators and prop makers and buyers – to name but a few.

It is only in a room where you feel the right to have a voice, that you can make your best work. If we want to give voices to women, then we need safe spaces to do so. This is about the direction of travel for our whole cultural sector and, while we can, and should, do better – the NT is a world leader.

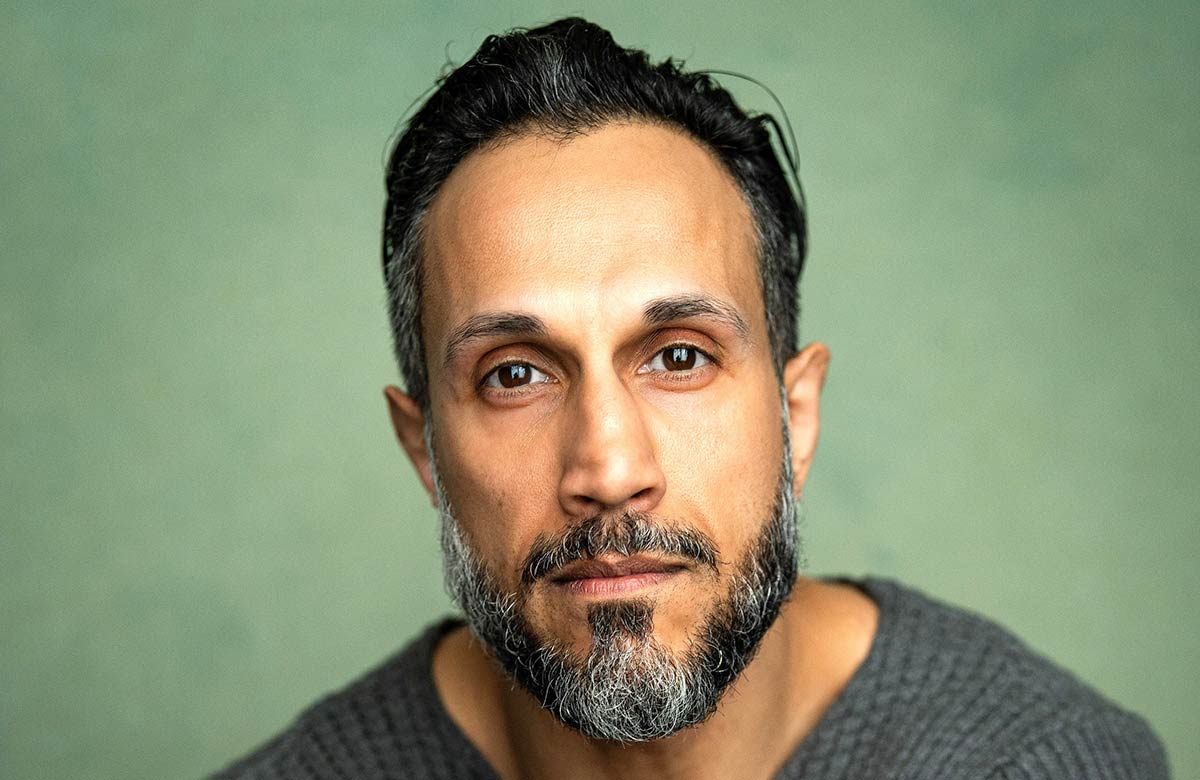

Paule Constable is a multiple Olivier and Tony award-winning lighting designer whose work includes productions for the National Theatre, Royal Shakespeare Company, the Donmar Warehouse, the Royal Court Theatre, Royal Opera and English National Opera

Theatre employers blame gender pay gap on imbalance in technical departments

Opinion

Recommended for you

More about this organisation

Advice

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99

Paule Constable

Paule Constable