Stephen Bourne: History shows us the hidden pioneers of black British theatre

Earlier this month, I had the joy of taking part in Palimpsest: A Celebration of Black Women in Theatre at the National. As a historian, it was my role to shed light on the early work of black women in British theatre, work often overlooked or even forgotten today.

From the unidentified actress who played Shakespeare’s Juliet in Lancashire in the 1790s to Cleo Laine, who made an acclaimed dramatic debut at the Royal Court in 1958 in a West Indian play called Flesh to a Tiger, there is a treasure trove of extraordinary stories waiting to be unearthed. The attendees at the event on London’s South Bank, which included drama students, actresses, playwrights and directors, were mostly black women. I suspect many had no idea about the pioneers, described by one of the organisers, Martina Laird, as “the women on whose shoulders we now stand”.

Sadly, there is so little available information about the early years of black British theatre. One reason is that in our schools and academies we tend to teach our young people about major African-American figures from history, such as Martin Luther King, at the expense of their black British counterparts. So, at the National, I spoke about Emma Williams, a West African woman who had a part in George Bernard Shaw’s Back to Methuselah in the 1920s, sharing the stage of the Royal Court Theatre with Edith Evans and a young Laurence Olivier.

After 1929, Emma vanishes but, when I began my work in the 1980s, I was fortunate to make friends with other black pioneers from British theatre, including Elisabeth Welch, Pearl Connor, Isabelle Lucas and Pauline Henriques.

Pauline was ambitious at a time when opportunities were few. In 1947 she did find work as an understudy for an American play with an all-black cast called Anna Lucasta. This transferred from Broadway to His Majesty’s Theatre in London and ran for more than a year.

Pauline told me with great pride that she organised Anna Lucasta’s black British understudies into the Negro Theatre Company. Two years later, Kenneth Tynan cast her as Emilia in an innovative production of Othello. I concluded my NT talk with Laine’s breakthrough at the Royal Court in 1958 in a play by the Jamaican Barry Reckord.

In 25 years of writing black British history books, I have shied away from dry, academic prose and always sought to get first-hand testimony from those who created the history; to find the surprising and positive stories, rather than the narrative – which strikes me as a rather racist one – in which black Britons from history are portrayed only as victims.

I have drawn strength from the many friendships I made with black pioneers and it has been particularly interesting to research the forgotten heroes of black theatre. It is important their empowering stories are told, that the old narratives are challenged, and that the place of those actors in theatre history is recognised.

If you’d like to read more stories from the history of theatre, all previous content from The Stage is available at the British Newspaper Archive in a convenient, easy-to-access format. Please visit: thestage.co.uk/archive

Opinion

Recommended for you

Advice

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99

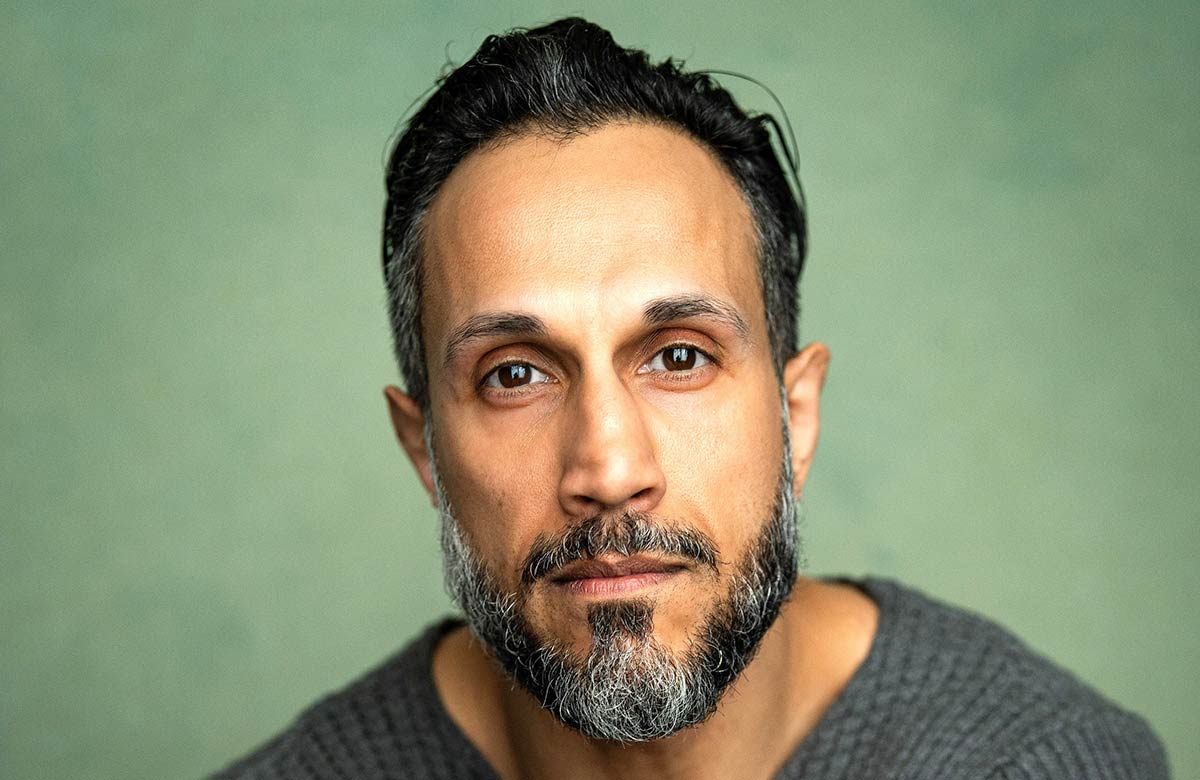

Stephen Bourne

Stephen Bourne