Let’s hear it for the understudy, the unsung hero of theatre

The show, they always say, must go on, and in the theatre, that means understudies are a fact of life. Actors are only human and will succumb to illness, like the rest of us. I’ve had a cold lingering for a week or so, but I can go on with my day-to-day activities for the most part – I don’t have to sing or perform. Actors in long-running shows are also entitled, like the rest of us, to take holidays. So understudies are a contractual necessity for any long-running show.

There’s a suspicion among audiences, of course, that they’re being short-changed; that if one or more of the leads are missing, they’re somehow getting an inferior piece of work. But the talent pool the West End draws on now is so big – and work so scarce – that you’ll invariably be seeing a star in the making or at least someone of considerable experience.

But critics don’t usually see them. That’s because we typically go to the opening or an early show in the run, when understudies are only put on in exceptional circumstances (the truth, too, is that understudy rehearsals typically only happen in earnest once a show actually opens; the creative teams are too busy tweaking the original cast to allow time for understudy calls as well).

And even when an understudy does go on at a performance we are attending, we are typically warned in advance in case we want to reschedule so we can see the entire cast instead. The other day I had planned to see Dirty Rotten Scoundrels again at the Savoy, in order to catch newcomers to the cast Alex Gaumond, Bonnie Langford and Gary Wilmot, but I was phoned by the show’s press representative to tell me that original cast member Katherine Kingsley was off that night – and so was her first cover, so I’d be seeing the second cover.

Far from putting me off, I jumped at the chance. It was Gaumond, Langford and Wilmot I’d wanted to see anyway, but it also gave me the opportunity to check out someone else entirely new, in this case Lisa Bridge.

According to her Twitter account, it was her first day going on in the role of Christine Colgate. Admittedly, by the time I saw her evening performance she had already done a matinee, but she was still in at the deep end. And what a confident, radiant pleasure she was. (In fact, it also made me wonder if she was raising the game of those around her: the rest of the cast couldn’t go on autopilot but had to respond to a performer who may have been doing slightly different things.)

There was never any tentativeness on her or their part; she was clearly well drilled to take over. Indeed the smooth professional running of a show – any show – is always a wonder to behold.

Indeed, one of the nice surprises was the warmth and ease of the entire company. When I first saw the show, I sensed a tentativeness and wariness around the stage. Performances didn’t seem to be connecting with each other or the piece. It wasn’t for me to speculate why this might have been, though when I dared to report my reaction on Twitter, star Robert Lindsay responded, calling me “a complete twat” (in a tweet he subsequently deleted).

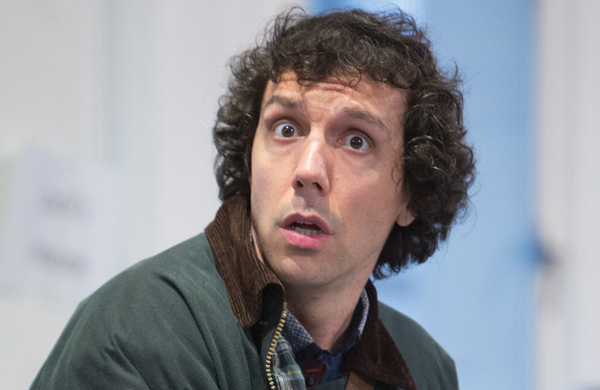

(Seeing the show again, I realised his tweet was only in character: he twice labels his rival-in-crime Freddy Benson – played originally by Rufus Hound and now with much more dash, charm and polish by Alex Gaumond – a twat. So I was in good company, at least.)

A lot of the smoothness may simply be that the show has settled down and the actors are more confident. But there was also a palpable change in atmosphere. That may also be down to the arrival of old pros Langford and Wilmot: they’re both actors who always radiate a joy at simply being there. Both are long-time leads relegated here to very much supporting roles, but they seize them with such aplomb that a spotlight seems to follow their every step.

But I wanted to turn the spotlight back on Lisa Bridge, if only because the production strangely fails to. Although I was personally notified that a cover would be on, the only warning that the audience gets is a small notice posted in the tiny, crowded box office foyer. Though a pre-show announcement is made about who is conducting the performance, no mention was made of an understudy in a leading role. Nor were slips provided with the programme.

Most people, I’d suspect, would have been entirely unaware that they were getting a cover. And maybe that’s a good thing: they weren’t made to feel disappointed before the show even began. But I doubt they’d have been disappointed by the time the show ended.

Opinion

Recommended for you

More about this person

Advice

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99

Mark Shenton

Mark Shenton