Learning to collaborate over distance can help your creative partnership

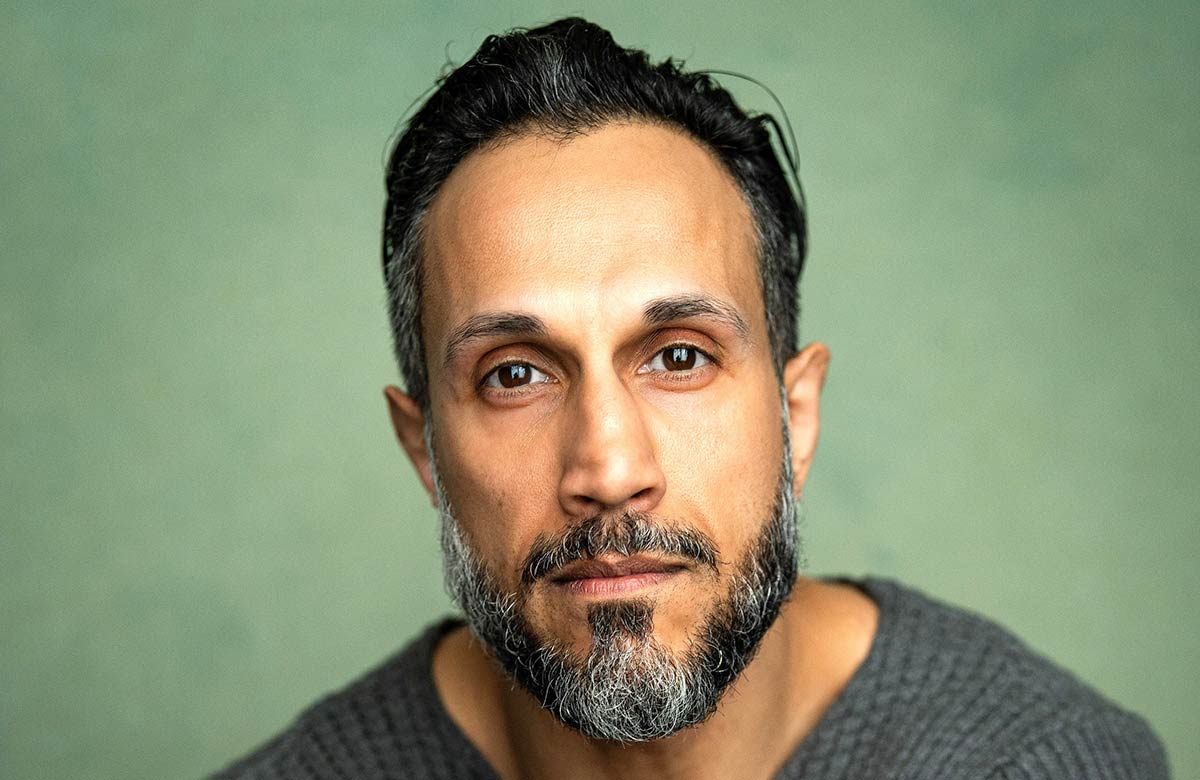

Collaboration can be a game changer in the creative process. For ex-Royal Ballet soloist Jonathan Burrows and composer Matteo Fargion the process of co-creation – but also distance – is what keeps them moving forward, and able to keep creating fresh new work, even after 25 years.

Burrows told me about the magic that the process of collaboration holds, saying that meeting Fargion helped him use his knowledge of classical ballet form, and take it forwards in a way that could ask questions, the way experimental work could. They both studied composition with the composer Kevin Volans, and that shared experience of studying built a common language that the pair draw on in

their work together. With Burrows’s influence from the dance and performance world, plus an interest in the theology behind it, combined with Fargion’s musical thinking, they cite the recognition of each other’s skill set as what keeps the process moving.

In Burrows’s words:

There are few people in the world you can find an easy flow of ideas with, and when you find them the best thing is to have as few meetings as possible. Matteo and I have spent a lot of our collaboration living in two different countries, and we learned that working at a bit of a distance we don’t get in the way of what each other does best. For the performance Cheap Lecture I wrote the whole thing before I even mentioned it to him, emailed it on New Year’s Eve and didn’t hear back until the spring, by which time he’d edited it, versified it, speeded it up and set it to music. For Body Not Fit for Purpose, Matteo proposed a daily practice of making something to the musical shape of La Folia, and the only real point of exchange early on was me persuading him that a piano was too heavy, so he switched reluctantly to a mandolin. Later on there was hourly exchange as the whole dramaturgy of the thing came into shape, something way beyond the original simple process, but we respond to what needs doing and try to cut space for each other when we can, and that way leaps get made.

For Fargion, most of the work he’s done in the past 30 years has been with choreographers, theatre directors or other composers. His advice is that choosing who you collaborate with is crucial:

When it goes wrong, it can be frustrating, soul destroying and disempowering and if there’s too much compromise you end up with a bruised ego and a weak piece. The work with Jonathan is on equal footing and we have developed clear strategies for dividing the labour. We don’t need endless discussions and negotiations after all these years. Sharing responsibility for the work is a lot less lonely, and it’s quicker to make decisions when there are two of you. Trusting each other’s instincts is crucial in a collaboration, as is being able to quickly let go of something you think is marvellous but the other doesn’t.

The balance of a shared process and new perspectives opens the artistic vision up and allows for more experiences to be drawn upon. As with any relationship, there needs to be room for harmony but also decision making and room for the unexpected.

Burrows continues:

Within our working relationship, Matteo tends to be the one who knows when to hold strong to an idea and not let it be compromised by fear and panic. At the same time I’m quite good at knowing when the thing we’re working on needs a wild card, or a sudden shift of approach, image or material.

One of the crucial elements in a collaborative piece between Burrows and Forgian is placing the musician on the stage. It’s an important aspect to Forgian, who says:

Of all our duets the most traditional in terms of me providing live music and Jonathan dancing is, perhaps surprisingly, the most recent one, Body Not Fit for Purpose. We decided, in an attempt to keep the conversation between music and movement on an equal footing, to sit at a table like two folk musicians might, casually playing through some tunes together. I might be deluding myself but I think unlike earlier attempts to present music and movement as equals this gets closer. And it certainly adds something to a performance to be negotiating the counterpoint between us live – it keeps the piece fresh as it’s subtly different every time.

Forgian also cites gentle questioning of what comes next rather than constantly trying to reinvent the wheel as something that keeps them creating new work:

What haven’t we done that we’ve talked about doing but haven’t got round to trying? We generally don’t need concepts or big ideas to get started, and often the subject of a piece will reveal itself as we go along. Sometimes it’s enough to imagine what the stage might look like when we walk on – do we stand or sit? Upstage or downstage? Is there a screen or a table? Microphones? Is language allowed? Some ideas don’t go away and eventually turn up: I’m still hoping for a piece in which I play a bass guitar and Jonathan’s on a drum set.

Jonathan Burrows and Matteo Fargion present their newest piece One Flute Note alongside the 2014 Venice Biennale commission Body Not Fit for Purpose, at the Lilian Baylis Studio at Sadler’s Wells on February 2 and 3

Opinion

Advice

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99