Robots and AI are taking centre stage in New York right now – actually, theatre is where they originated

It is perhaps overstating the case to say that robots are taking over New York theatre this November, but artificial humans certainly are having a bit of a moment.

Broadway has activated its upper-torso appendages to embrace Will Aronson and Hue Park’s Maybe Happy Ending, the musical story of two humanoid robots who find love in a retirement community (read: warehouse) for discarded machines. The pair meet-cute when one faces imminent power loss and then must surmount the obstacle of being of different models (is this a potential mixed marriage, of two circuit boards both alike in dignity?), but somewhere within their sophisticated silicon the two forge a bond.

Stage robots require us to consider how we treat those unlike ourselves, and the dream or even futility of making more perfect versions of people

Off-Broadway at Theater for a New Audience in Brooklyn (co-produced with Rattlestick Theatre), Ethan Lipton presents himself and his band as robot ambassadors to a consideration of how humans interact with technology and what the future may hold in We Are Your Robots. Filled with wry, sardonic songs and ruminations, it is billed as a musical, but is perhaps better described as a stand-up hipster TED Talk and concert on the theme of artificial intelligence and humanity, an entertainment but not a narrative per se.

Both come on the heels of Ayad Akhtar’s McNeal at Lincoln Center Theater, slightly corollary to the topic, with its story of a famed novelist who uses AI to build a new book out of the attributes of his prior works. As McNeal, Robert Downey Jr converses with a highly sophisticated cousin to Apple’s Siri crossbred with ChatGPT to create the work, but unlike the true robot plays, there isn’t a human-like figure hanging out in his home.

Continues…

In this era of AI coming into daily life, it shouldn’t be surprising that robots are taking centre stage – after all, it’s the theatre where robots originated. Well, the word robot, at least. While terms such as “automaton” and “android” can be traced to writings more than 300 years ago, “robot” emerged in 1920 thanks to Czech playwright Karel Čapek’s R.U.R., an abbreviation that stands for Rossum’s Universal Robots. The play was a hit in England and the US, and many other countries as well.

Humanoid figures had been on stage even before R.U.R. gave them a new name. In an essay this week in the New York Times, Jason Farago considers Offenbach’s Les Contes d’Hoffmann and the often balleticised Coppélia (also adapted from ETA Hoffmann’s works), both seen this autumn across the plaza from one another at Lincoln Center.

But Čapek’s story of robots crafted for servitude that ultimately rise up against humanity echoes the first science fiction story, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein – then a century old – in its consideration of what humans could do, whether they should do it, their responsibility to what they created and the possibly dangerous and tragic outcome.

By inventing the word robot, Čapek clearly wanted morals and ethics baked into discussions of artificial humans, as the term was a slight alteration of the Czech word for forced labour. The play emerged in Eastern Europe shortly after the Russian Revolution, and the topic of labour versus a ruling class is unmistakable.

In Maybe Happy Ending, while its core is romance, audience members are forced to contemplate why these still-functioning humanoids have been warehoused to live out their days in little cubes; remarkably, elder care is evoked. In We Are Your Robots, Lipton’s own somewhat sad countenance (topping a smartly tailored suit) and comedic detachment lends a mournfulness to his low-key rumination on machines and man. Theatrical robots are rarely simply devices for adding a soupçon of tech or threat.

Continues…

Despite their origin on stage, robots have tended to be the provenance of science fiction and fantasy literature and films. On hearing the word, we likely think of the Machine Man of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, the sentinel Gort from The Day the Earth Stood Still, the maid Rosey from The Jetsons, the duplicitous Ash in the original Alien or the replicants of Blade Runner. Yet they have their theatrical brethren.

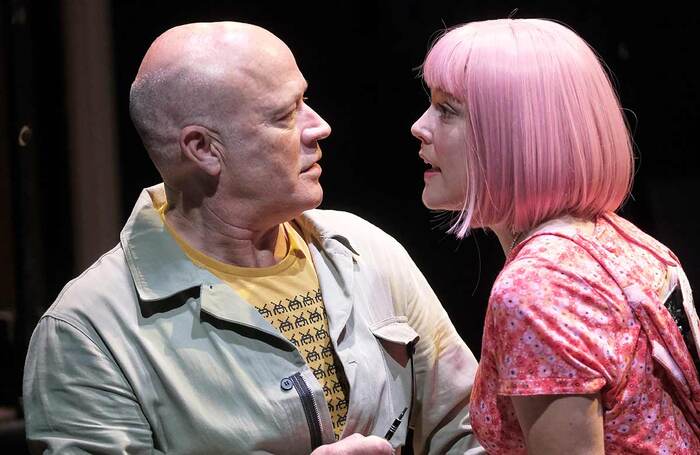

Alan Ayckbourn has perhaps been the dramatist who has most considered what the advent of robots could mean for human life, setting the perfection and sometimes imperfection of machines – and people – into situations that showed how they might co-exist, both happily or uneasily. His first major robot play, Henceforward…, was set in a dystopian future, yet a decade later he took a sunnier approach in the romantic Comic Potential, with human-robot romance. Nonetheless, Comic Potential suggested that the very task of acting, at least in such efforts as televised soap opera, might see humans replaced by actoids.

The rise of AI, which has always been an implicit element of robot plays, will only fuel more dramatic works as it comes into its own in reality and not just fantasy

In his 2012 play Surprises, Ayckbourn posited another human-robot symbiotic relationship – was it really love after all? – in a play that more broadly hinged on time travel. A decade later he jettisoned the time-travel narrative in Constant Companions, a play entirely about humans and their robots, built around the human-robot scenes from Surprises, largely unaltered but expanded with other comparable relationships. A new play, yet unproduced but read publicly at Scarborough’s Stephen Joseph Theatre in September, Father of Invention, explores the legal rights of robots alongside humans.

US-originated robot plays include the Pulitzer Prize finalist The (Curious Case of the) Watson Intelligence by Madeleine George, a multi-strand story of learning and love that deployed Dr Watson of Baker Street; Alexander Graham Bell’s telephonic collaborator, Mr Watson; the IBM supercomputer Watson, and an exceptionally helpful IT nerd, also named Watson. Jordan Harrison’s Marjorie Prime, also a Pulitzer finalist, proposed a future in which humans can find companionship late in life with replicas of their deceased loved ones, perhaps not as they were at their end, but during their, well, prime. George’s play is intellectually playful, while Harrison’s is elegiac and contemplative.

Continues…

Regardless of their form, robots on stage always exist to force us to contemplate ourselves, with their potential obsolescence, decline and final shutdown mirroring our own cycle of life. Stage robots also require us to consider how we treat those unlike ourselves, the dream or even futility of making more perfect versions of people, and what it is that gives biological life its true spark. Robot plays most often ask us less whether we’re capable of building such simulacrums, but whether they too can have souls. The rise of AI, which has always been an implicit element of robot plays, will only fuel more dramatic works as it comes into its own in reality and not just fantasy.

Can we connect with robots one day as equals, as a new form of life deserving of the same equal rights that humans often still deny to other humans? That is for the philosophers and ethicists – and the playwrights – to contemplate. But I will say that I laughed hilariously when a certain mass-produced robot took to the stage several times in We Are Your Robots, showing that machines can spark joy. And there is a piece of my heart that still belongs to Comic Potential’s Jacie Triplethree, which I lost to her one afternoon in Scarborough back in 1998. I may not be prepared to welcome our robot overlords to the world, but I am prepared to welcome them to the theatre.

Opinion

Recommended for you

Advice

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99

Howard Sherman

Howard Sherman