George Coles: Radical GCSE drama overhaul risks killing students' passion

August 24 will be a sad day for GCSE drama. The final cohort of students will receive their award as an A*-G grade. Next year, students will receive a 9-1 grade having taken a qualification that looks drastically different from the one proceeding it, most notably the shift from 60% practical assessment to 30%.

Radical reforms have meant teaching entirely new content with assessment focused on written work over process and performance-based assignments.

The Department for Education has claimed the reforms “will create gold-standard qualifications that match the best education systems in the world and allow young people to compete in an increasingly global workplace”.

But it does feel as though some of the passion has left my drama studio.

Over Easter, I had the privilege of watching my students stage their own versions of Eugene Ionesco’s The Bald Prima Donna, Sarah Kane’s 4.48 Psychosis and Andrew Bovell’s Things I Know to Be True with intelligence and nuanced understanding far beyond their years. All could discuss character motivation and dramaturgical choices in their play while explaining the cultural, historical and political context underpinning their work and its relevance to the audience. They were immersed in the inimitable process of real-life theatremaking and no amount of written work could match that deep level of learning.

In the newly reformed GCSE, 10% of practical work is assessed through a devised performance and 20% through a scripted piece, comprising two short ‘extracts’. This means that two students could perform two extracts together with a total performance time of a mere three minutes. While they are expected to explore their entire play in full, there is little motivation to give it much thought as they see it as a box-ticking exercise.

Previously, I have seen students alive and brimming with ideas, bringing costumes and props in from home, writing lighting and sound cue sheets and rehearsing late into the evening. Now, inevitably, some students feel apathetic towards performance work as they know it is worth so few marks.

Some of my colleagues teach most of the new specifications behind desks, but surely this is not the best way to teach our subject? I am determined to give my students meaningful opportunities to create and respond to challenging theatre that keeps them inspired.

Making theatre requires a skills that can only be developed through practical training, and my drama GCSE was instrumental in preparing me for actor training at Rose Bruford College.

The move away from practical work will have implications for the next generation of actors, technicians and theatremakers. Furthermore, the DfE’s ideological assertion that the new qualifications better prepare young people for work seems nonsensical.

Making theatre cultivates communication, empathy and problem-solving skills. Surely these will best equip students for the future?

Opinion

Recommended for you

Advice

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99

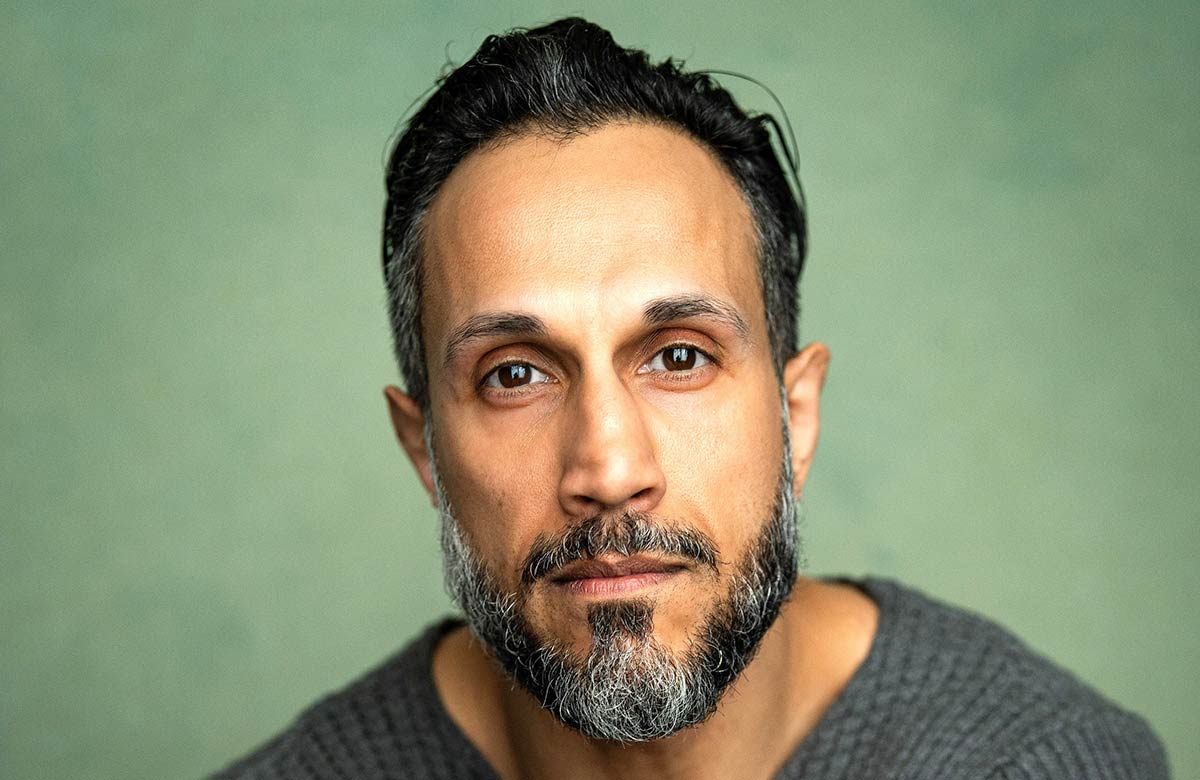

George Coles

George Coles