Critical crossroads

No one ever built a statue to a critic, as the Finnish composer Jean Silbelius once commented, but two critics recently received OBEs in the Queen’s New Year honours list. Michael Billington and Philip French, respectively chief theatre and film critics for The Guardian and The Observer, have been honoured after writing reviews in their particular disciplines for 100 years between them.

And this year marks another centenary – that of the Critics’ Circle itself, whose separate annual theatre and film awards have both just taken place. So critics have been around for a long time, and are still having a demonstrable influence in setting the cultural agendas of the areas they cover. But will they be around much longer?

A few years ago, I wrote a feature titled ‘What’s the point of critics’, and I quoted some of my colleagues’ reactions to the Queen musical We Will Rock You, as well as my own. “Only hardcore Queen fans can save it from an early bath,” wrote my then Daily Express colleague Robert Gore-Langton, and I myself called it a “grim spectacle” and “tacky, trashy tosh” in the Sunday Express. We were not alone in our views.

But more than a decade later not only is the show still running, it also won a special Audience Award at the 2011 Olivier Awards in a public vote for people’s favourite show.

Is this a rebuke to the so-called power of the critics? And just as importantly, how are critics being affected by the changing fortunes of the outlets where they write? The influential US current affairs magazine Newsweek proclaimed on the front cover of its December 31 issue that it was the last print edition ever. Not only are the traditional distribution channels of the print media changing, but also the online world is one in which blogs, bulletin boards, chatrooms and Twitter are offering far more outlets for opinion. The result is that far from being the ultimate word on a production, critics are only the start of a conversation around it, not the end of it. It means the discussions that critics are part of are now richer as they have had to become more engaged with both those they write for and those they write about more than ever before.

It also means that there is a lot of noise to filter before readers get down to the authority of people actually appointed (rather than self-appointed) for their expertise and knowledge. And amid all the noise of the internet, authoritative voices are even more important than before. But establishing one of those does not require the backing of a professional media organisation anymore. The ability to set up and manage a blog may be all that is necessary, as the West End Whingers proved over here, with a catchy name and an even more catchy turn of phrase that gave them international notoriety when they dubbed Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Love Never Dies as Paint Never Dries.

[pullquote name=”David Lan, artistic director, Young Vic”]One way you try and talk to your audience is to say ‘it’s not too big a risk’ or ‘it’s worth taking a risk on’. What the critics can do when they write about a show is create that confidence in it[/pullquote]

More seriously, the academic and writer Jill Dolan won the George Jean Nathan Award, America’s biggest theatre criticism award last year, for her blog The Feminist Spectator.

Writing in a Guardian blog, Karen Fricker – another academic and part-time critic – noted at the time: “One can’t also help but feel a pragmatism in the committee’s decision – opening up to bloggers means that they’ll continue to have people to give the award to.”

Indeed, in the last few years, New York has seen the elimination of the role of theatre critics on a number of leading publications. As Michael Riedel wryly noted in a column in the New York Post a couple of years ago: “Being a member of the New York Drama Critics’ Circle these days is like being in a revival of Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None.”

He was reporting the layoff there of Journal News’ Jacques le Sourd, who had served as critic for 35 years. And as le Sourd wryly observed: “My next assignment was on the Depression hits Broadway. I don’t have to do that story now. I’m living it.”

Strangely, though, despite the falling numbers of full-time positions for professional critics, the demand for press tickets has increased. West End press reps report that publications now often request tickets for both their print and online editions, while the number of blogs and websites asking to review has increased exponentially and to such an extent that each press rep has to determine their own cut-off point (perhaps based on web readership data) to decide who gets tickets.

The Edinburgh Fringe provides a nearly perfect working model of what the future may look like. Just as the fringe provides the ultimate form of democracy, where there are no barriers to entry and anyone can put on a show, so anyone and everyone can review it, too.

But, actually, out of that cacophony of voices out there, the critic who not only has something to say but is also listened to is more important than ever. Amid the welter of unknown bylines, The Guardian’s Lyn Gardner’s tenacity and dedication in seeking out the most interesting work make her contribution all the more authoritative.

Gardner makes her living by doing so. But it is becoming increasingly difficult for critics. When Edward Seckerson recently resigned as chief classical music critic of The Independent, he revealed that he was being paid just £90 a review – down from the £150 he used to be paid.

Professional critics are important to the theatre community. In Los Angeles, where a number of leading critics have lost their jobs, the artistic directors of three of LA’s leading theatres – Gilbert Cates of the Geffen Playhouse, Sheldon Epps of the Pasadena Playhouse and Michael Ritchie of Center Theatre Group – wrote an eloquent joint letter decrying the situation. As they say: “It may seem somewhat ironic that leaders of arts institutions would come out in favour of further criticism. It would be like fire hydrants getting together to come out in favour of more dogs. But, as artistic leaders who run three of the larger theatre organisations in Los Angeles, we’ve recently become worried. Over the last few months there has been a conspicuous disappearance of arts writers and editors in our local papers.

“Criticism is always difficult to hear, especially if it comes from friends, relatives, acquaintances, neighbours, strangers, bystanders or casual observers. But it is even harder to bear when one realises that criticism is being shared publicly with thousands of readers and may form the basis of their own opinion toward your work. Yet we depend on the voices of critics and arts reporters to help create a conversation with our community. If we let these voices slowly and quietly disappear, the consequences are simple and inevitable: fewer people will know about the productions, fewer people will purchase tickets, and eventually, fewer theatres will exist.”

So, to adapt the old adage “If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?”, if a theatre production opens and there is no one to list or review it anymore, has it actually happened? Of course it has. But reviews act as a permanent record of an ephemeral art, and they also encourage people to attend and support it before it passes. We lose that at our peril. And artists are realising it, even if editors and proprietors are not.

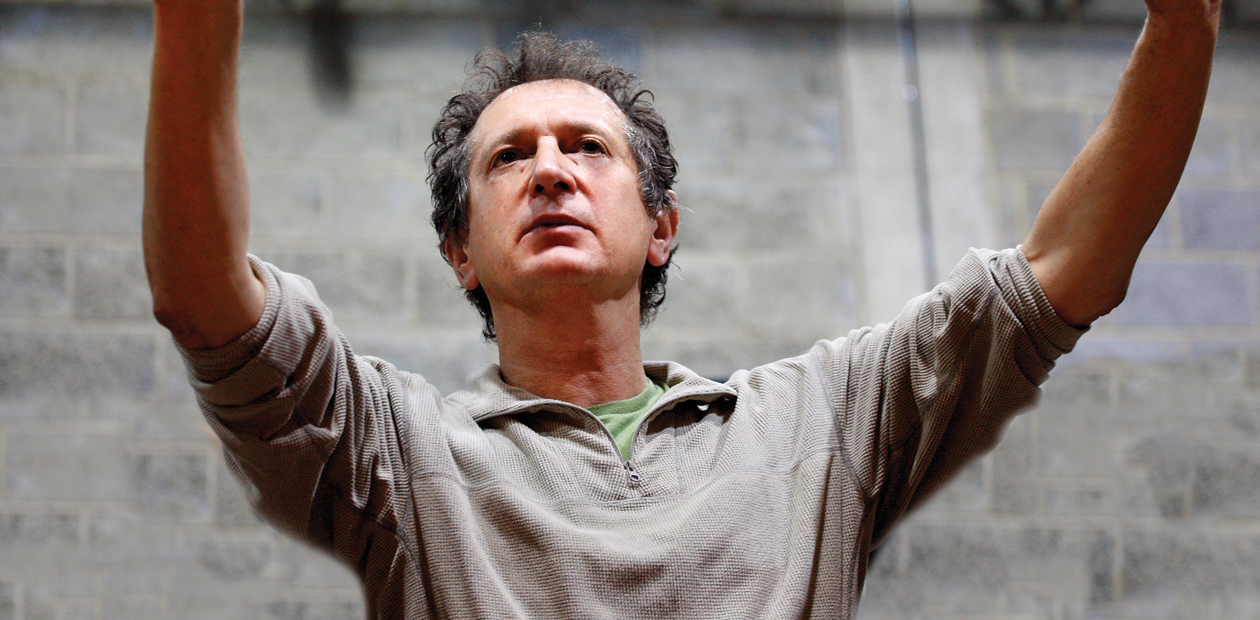

As David Lan, artistic director of the Young Vic, told The Stage just last week when his organisation won three of the nine Critics’ Circle Theatre Awards: “To receive these awards from critics is helpful. One of the things the critics do is create confidence in a piece of work. There are some other ways of creating that confidence – partly the reputation of the theatre and partly the reputation of the actors. Not many people think too much about the directors but they’ll also think about the writers. One of the ways you try and talk to your audience is say ‘it’s not too big a risk’ or ‘it’s worth taking a risk on’ and what the critics can do when they write about a show is create that confidence in it.”

Just how long they will still be around to help create that confidence remains unclear.

Mark Shenton is theatre critic of the Sunday Express, regular contributor to The Stage, including a daily online column, and chairman of the drama section of the Critics’ Circle

Opinion

More about this organisation

Advice

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99

Mark Shenton

Mark Shenton