Arts policies that neglect young people are in need of a metamorphosis

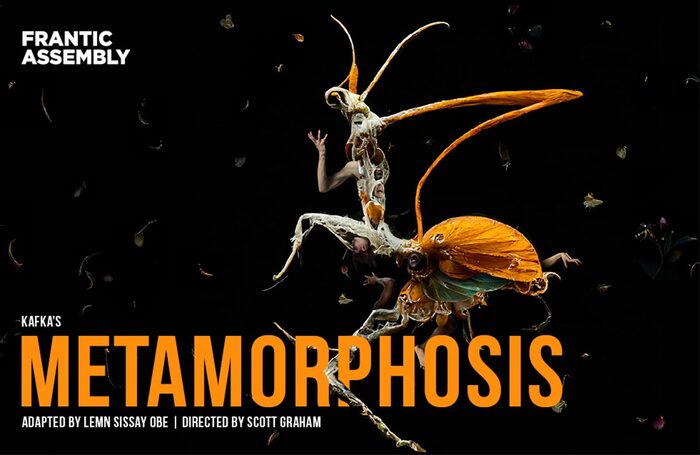

In Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis, Gregor Samsa wakes up transformed. In Frantic Assembly’s upcoming stage version of the novella, adapted by Lemn Sissay, directed by Scott Graham, and setting out on tour from Plymouth in September, Samsa is under huge pressure to support his family. One of the things he dreams of achieving is helping his sister Grete pursue her ambitions to play the violin.

“One of the elements of the story is about aspiration, and what people from different backgrounds can aspire to, and that feels really timely because of the articulation of the idea that people from backgrounds like Grete’s can’t play the violin or shouldn’t aspire to a career in the arts,” Graham tells me when we speak.

For Graham, the co-founder (with Steven Hoggett) of Frantic – indisputably one of the great companies of the past 30 years – enabling access to the arts has been key, both personally and for the company. When he founded Frantic, it was still possible (just) for anyone from any background to start a theatre company.

No more. As Arts Emergency chief executive Neil Griffiths recently observed, calling upon Labour to be more specific about its promises to ensure every child has a broad and balanced education: “The sad truth of government policies for higher education is that they appear to have returned us to an earlier time when ‘culture’ was understood to be the rightful domain of a privileged upper class.”

It is a measure of how far our educational system is locked in 19th-century models when creativity is so neglected within the curriculum

Despite initiatives to widen access by individual arts organisations, a lack of impetus for real change in the arts combined with government policies on arts education and funding cuts have left many millions of children growing up in the UK as Gretes. It is a measure of how far our educational system is locked in 19th-century models when creativity – such a key skill for jobs in the fourth industrial revolution – is so neglected within the curriculum.

For the many Gretes, their postcode, family income or ethnicity puts access to theatre and music out of their reach.

It makes the thought of entering an industry over whose shape they have so little influence seem as remote as Mars. But it’s not just their future that will be the poorer: it will be theatre’s, too. It needs new voices; new and different ways of seeing and meeting the world. It needs young talent, technical and other.

Continues...

Some arts organisations have recognised that without the voice of youth in your organisation, it’s not just the young who have no future, but your organisation that will face terminal decline. The youth-focused Roundhouse in London has been exemplary in that respect and has long had a youth board and youth representation on its main board.

Back in 2019, the Royal Shakespeare Company, already engaged in consistently fine work in schools, appointed its own youth advisory board. I recently took part in the selection for the RSC’s 37 Plays project, and members from the youth board gave invaluable input. Young people’s voices do matter, so why do we so seldom listen to them?

There’s a chance for that this week, when the RSC holds its first Young Creatives’ Convention, during which 300 young people from arts organisations across England will make the case themselves why arts education matters and speak directly to policymakers both in the arts and government.

There will be a session with the Department for Education, which will feed into the government’s Cultural Education Plan (there are some good people on the plan’s recently appointed expert panel, including the RSC’s own Jacqui O’Hanlon, Contact Theatre’s Keisha Thompson and Second Hand Dance’s Rosie Heafford), and others on training opportunities in the arts and mental health.

It’s good to see that the RSC’s new co-artistic director Tamara Harvey will be chairing one session, an indicator I hope that the new regime recognises that its education work should be supported and given as much weight as deciding what gets programmed in the Swan and who directs it.

The two are, of course, intimately connected. The RSC’s current revival of The Empress, directed by Pooja Ghai, reflects how the company is supporting the wider needs of teachers who may not choose to teach curriculum texts that offer greater representation if they do not feel confident teaching those texts. Being able to see them staged helps enormously. That’s an arts organisation being a good ally of teachers.

It will be interesting to see what emerges from the convention, but, as O’Hanlon told me, the young people present will be those who will be most affected by the decisions being made by education and arts leaders now, so it makes sense for their voice to be heard. She added: “There are lots of conversations in the industry about pipeline. But how can the industry understand how it needs to shape itself for the young people who are going to come through it unless it listens to young people and uses that to inform the decisions made?”

Opinion

Recommended for you

More about this organisation

Advice

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99

Lyn Gardner

Lyn Gardner