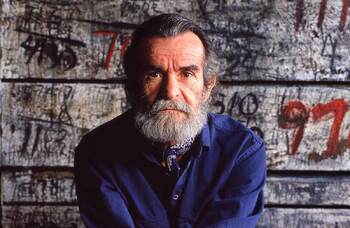

Obituary: Peter Hall

Peter Hall, who founded the Royal Shakespeare Company in 1960 and moved the National Theatre into its new South Bank premises in 1975, is arguably the dominant figure in the post-war British theatre, and certainly the architect and greatest impresario in the modern era of state-subsidised theatrical endeavour.

He directed the British premiere of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, the first truly modern play, as well as the major plays of Harold Pinter, notably The Homecoming, Old Times, No Man’s Land and Betrayal. His Wars of the Roses sequence at the RSC was the major Shakespearean event of our day: he established new principles of relating Shakespeare to the modern world, of verse-speaking and set design, and of a resident ensemble in the European style.

“Other people had dreamt of these things; Hall drove them through,” said Irving Wardle, former drama critic for the Times. In the face of concerted opposition from West End producers, Hall established a London home for the RSC at the Aldwych. And when the National’s board clumsily dismissed Laurence Olivier in his favour, he had to combat first professional resentment, then a series of industrial disputes climaxing in the strike of stage technicians (after a plumber had been sacked) during the three-day week nightmare of 1979.

As a result, his distinction as a director was often subsumed by the grander status his job demanded. This pre-eminence – and this being Britain, where the argument for subsidising the arts has never been convincingly, or resoundingly, concluded – was always beset by a sense of frustration and indeed incipient failure. But Hall, who thrived in adversity, despite suffering from depression, fuelled his mission to succeed with an unshakeable personal ambition and boundless energy. And his appetite was, in every sense, insatiable.

Everything he did seemed a fulfilment of his own destiny. The only child of a Suffolk station-master and a somewhat critical mother (whose own father had been a rat-catcher) in Bury St Edmunds, he decided, on a school trip to Stratford-upon-Avon in 1946, aged 15, where he saw Peter Brook’s famous Watteau-esque Love’s Labour’s Lost, that he would run the place himself one day.

In his last year as a scholarship boy at the Perse School in Cambridge he played Hamlet and won a place at St Catharine’s College in that city’s university. In his first week there, he booked the ADC Theatre for the first week of his final year. Two weeks after graduating in 1953, and having directed more than 20 student productions, many of them for the Marlowe Society, he made his professional debut at the Theatre Royal, Windsor in 1953, directing Somerset Maugham’s The Letter.

At the Oxford Playhouse, where he directed two seasons in 1954/5 alongside Peter Wood, he accompanied Maggie Smith at the piano as she sang The Boy I Love Is Up in the Gallery. But once at the Arts in London, where he was appointed ‘producer-in-chief’ in 1955, Hall changed his tune, directing The Lesson, the first play of Ionesco’s to be staged in Britain. This was followed by Eugene O’Neill’s Mourning Becomes Electra and then Waiting for Godot.

The latter play’s notoriety secured his own reputation – assisted with reviews by Harold Hobson and Kenneth Tynan – and Hall soon heard from Harold Pinter (although Peter Wood directed The Birthday Party in 1958) and Tennessee Williams, directing the latter’s British premieres of Camino Real and Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. He was first invited to Stratford-upon-Avon in 1957 and directed Peggy Ashcroft in Cymbeline, followed by Olivier in Coriolanus and Charles Laughton as Bottom in A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Hall was the new heir apparent, succeeding Anthony Quayle and Glen Byam Shaw at the Stratford helm, and persuading his chairman, Edward Fordham Flower, to change the name of the theatre (from the Memorial to the Royal Shakespeare), rebrand the company as the Royal Shakespeare Company, drop anchor at the Aldwych and hire a company of actors on three-year contracts.

The National Theatre was still three years away, and that lobby bristled with annoyance at what seemed like Hall’s pre-emptive strike. But his momentum was unstoppable, bolstered by Ashcroft’s support and that of fellow directors Brook and Michel Saint-Denis, as well as his old Cambridge friend John Barton.

Hall directed an extraordinary production of Schoenberg’s Moses Und Aaron at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, in 1965, the same year as he cast David Warner as a definitive, highly original and critically reviled RSC Hamlet. In a production in which Glenda Jackson was the first sexually psychotic Ophelia, Warner was a genuinely disaffected student prince three years before the Paris evenements.

Trevor Nunn succeeded Hall as the strain took its toll on his health in 1968, and he concentrated on opera before succeeding Olivier at the National.

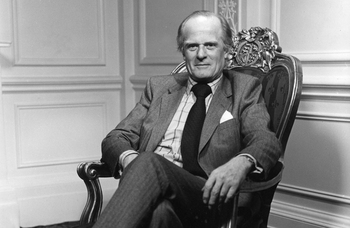

There was brief talk of Hall and Nunn amalgamating the two monoliths, then of Nunn becoming Hall’s deputy at the National. Instead, Hall ploughed on with renewed vigour for the next 15 years, creating various companies within the NT itself – led by the likes of Ian McKellen, Michael Bogdanov, Bill Bryden and Alan Ayckbourn – and directing Pinter’s No Man’s Land (1975) with Gielgud and Richardson, Albert Finney as both Hamlet and Tamburlaine, Peter Shaffer’s Amadeus (1979) with Paul Scofield and Simon Callow, Tony Harrison’s version of The Oresteia (1981) performed in masks, and McKellen’s Coriolanus.

In 1985, when the Arts Council’s increase on its subsidy registered at least 5% below what Hall reckoned was needed to maintain productivity, he closed the Cottesloe in a famous ‘coffee table’ speech (he stood on such a table). But he battled through, as always, seeing off both the general media hostility that never abated until Richard Eyre succeeded him in 1987, and the rancorous opposition of the old Olivier guard, so dramatically charted in Michael Blakemore’s National Theatre memoir, Stage Blood.

Hall was stigmatised as ‘Genghis Khan’ or ‘Dr Fu Manchu’, but his apparent greed and power lust were symptomatic of how he functioned as both director and executive. He was accused of moonlighting when he disappeared to Glyndebourne or the television studios (where he presented an arts programme, Aquarius). He even loaned his name to an advertising campaign for wallpaper: “Very Peter Hall, very Sanderson.” Very embarrassing.

On leaving the National, he formed the Peter Hall Company – again setting a sort of precedent for people such as Michael Grandage and Jamie Lloyd – which operated in conjunction with a series of West End managements, notably Triumph and then Bill Kenwright, interspersed with seasons of classics and new plays at the Old Vic (with Dominic Dromgoole) and the Theatre Royal Bath (from 2003) and finally the new Rose Theatre at Kingston, which he opened in 2008 with a worthy, unexceptional Uncle Vanya.

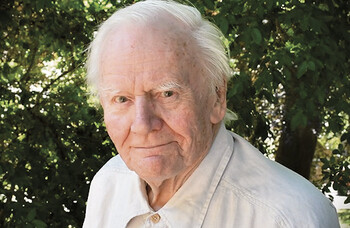

He was now the eminence grise, his final two decades of activity marked, in the early Peter Hall Company period, with some outstanding work, including Vanessa Redgrave in Williams’ Orpheus Descending and Dustin Hoffman in The Merchant of Venice, as well as some that was frankly routine, bordering on the bad, such as the American co-production of Barton’s long-simmering Tantalus project in 2000 and the damp squib Twelfth Night at the NT in 2011 with his daughter Rebecca as Viola.

Hall was a greater encourager and developer of young talent. Speaking to The Stage when he received The Stage Award for outstanding contribution to British theatre in 2011, he declared himself optimistic about the state of young performers, declaring them “much more hard-working, more technically interested and they are – God save them – less keen on their billing, more modest”. However, he did express concerns about verse-speaking, especially of Shakespeare.

“There are about 50 or 60 actors in this country who can really stand up on stage and speak Shakespeare. There are 100 who would like to have a try. I think one can encourage a young actor into Shakespeare in two days, if he’s the right actor. Some small percentage just can’t deal with it.”

For someone so brilliant in the opera house, and so musically gifted – his Glyndebourne A Midsummer Night’s Dream by Britten in the old house is one of my desert island productions – his forays into musical theatre, always adventurous, were invariably flops, ranging from Galt MacDermot’s Via Galactica (1972) on Broadway to Marvin Hamlisch’s Jean Seberg (1983) at the National and, most excruciating of all, Born Again (1990), a musical version of Ionesco’s Rhinoceros designed by Gerald Scarfe, at Chichester.

He never tired of returning to his favourite works – The Marriage of Figaro, Waiting for Godot, Twelfth Night – and he never tired of supporting and defending his colleagues in the theatrical network he had largely created himself, nor of railing against bureaucracy – although he himself was a brilliantly manipulative committee man. He had the rare knack, too, of making whoever he was talking to feel as though he or she was the only person in the room who mattered. He was a titan, a rare visionary, a sensual charmer. David Hare described him fondly as “Rabelaisian”.

In his early days, Hall was a genuine celebrity and that of course also contributed to the outbreak of tall poppy syndrome that accompanied his every move. But he was sustained in his rich and colourful personal life by the love of four successive wives – film star Leslie Caron (mother of Christopher and Jennifer), Jacqueline Taylor (mother of Lucy and Edward, the director), opera singer Maria Ewing (mother of Rebecca, the actor) and Nicki Frei (mother of Emma) – six children and many grandchildren.

He was made CBE in 1963 and knighted in 1977. He was a member of the Garrick Club – but never went there – and published two remarkable and essential books: Peter Hall’s Diaries (1983), covering his tumultuous first decade at the National, edited by John Goodwin; and a compelling autobiography, Making an Exhibition of Myself (1993), a title suggested by one of his mother’s accusatory sideswipes at his meteoric success story.

Peter Reginald Frederick Hall was born in Bury St Edmunds on November 22, 1930 and died, at the age of 86, on September 11 at University College Hospital in London, having been diagnosed with dementia in 2011.

Peter Hall timeline

1955 Directs London premiere of Waiting for Godot at the Arts Theatre and causes a sensation, though Beckett himself never liked the production

1957 Directs Coriolanus at Stratford with Laurence Olivier in the lead and Albert Finney his understudy

1960 Founds RSC on principle of homes in Stratford and London and establishes a permanent company in both Stratford and London. An acclaimed Twelfth Night with Dorothy Tutin.

1964 First ever complete Wars of the Roses cycle at Stratford for Shakespeare’s quatercentenary. Directed with John Barton and Clifford Williams, this establishes the RSC as a European ensemble

1965 Directs Pinter’s The Homecoming in a monumental set by John Bury. Ian Holm’s Lenny is a counterpart to the actor’s Richard III, embodying policy of Shakespeare and contemporary work on a similar scale and ambition

1971 Co-director, Royal Opera House, Covent Garden

1973 Director, National Theatre, directing Gielgud and Richardson in Pinter’s No Man’s Land (1975) at the Old Vic and West End

1976 New NT home opened by the Queen on the South Bank, where Hall directs Finney in Hamlet and Tamburlaine the Great and, in 1981, a great production of Tony Harrison’s version of The Oresteia of Aeschylus, in masks

1984 Director, Glyndebourne Opera

1988 Forms the Peter Hall Company, with seasons at the Old Vic and the Theatre Royal Bath

1999 Olivier special award for lifetime achievement

2008 Opens the Rose Theatre, Kingston, to a mixed reception, the space proving hostile to successful – intimate or epic – versions of the classics and new work, an ironic coda to RSC glory days

2011 Receives The Stage Award for outstanding contribution to British theatre

Latest Obituaries

More about this person

More about this organisation

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99