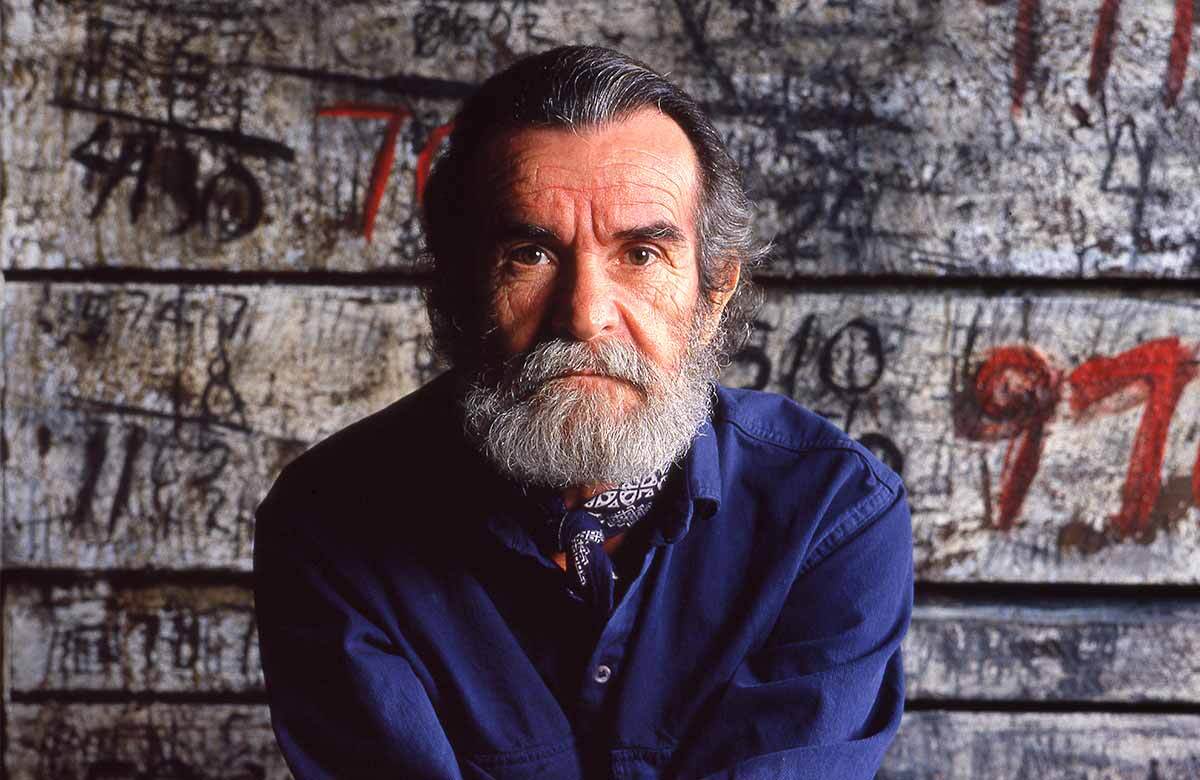

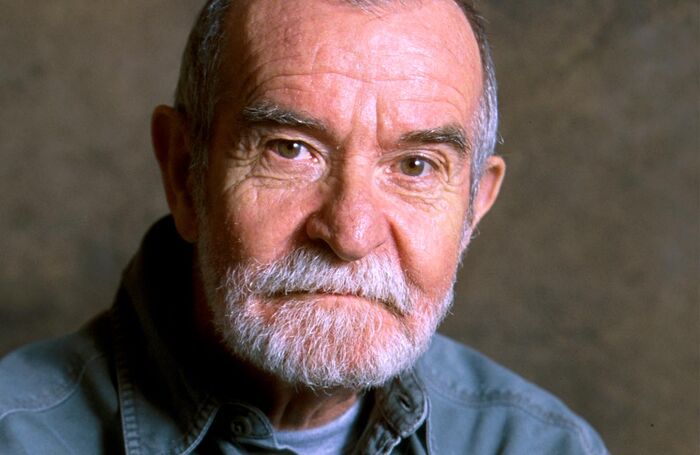

Athol Fugard

Prolific South African playwright whose work exposed the corrosive effects of the political and social system of apartheid

When playwright Athol Fugard’s first play to receive international recognition, The Blood Knot, played in London in the early 1960s, it was met with disfavour by the reigning critic of the day, Kenneth Tynan – “damned out of existence” were Fugard’s own words in a 2010 interview. He related returning to South Africa, being told by many that his work needed to be opened up for the wider English-speaking world.

“You made the play too local, too South African. You had limited yourself,” Fugard recalled of the advice he was given. “Can you imagine giving that advice to William Faulkner? Whatever strength or quality there is in my plays comes out of that regionalism, comes out of the fact that the plays are time and place specific.”

In particular, Fugard’s work was driven by the impact of the racist South African policy of apartheid, under which the black majority population was deemed subordinate to the white ruling class. The result was a body of some three dozen plays depicting the human impact of the inhumane government policies on black and white citizens alike. As international opposition to apartheid grew in the 1980s, Fugard was the foremost stage conduit to understanding the insidious and debilitating policy.

In a rigorously and often violently segregated country, Fugard worked from his earliest days in the theatre alongside black artists, including several who would remain creative partners for decades: John Kani, Zakes Mokae and Winston Ntshona. The Blood Knot explored the lives of half-brothers whose status in the wider world and ultimately their own relationship was determined by their skin colour, as one of the brothers, played by Mokae, was dark skinned, while the other, played by Fugard, could pass for white.

Continues...

This set the template for Fugard’s work throughout his career: taking on forces beyond the control of the characters by looking at how they influence the day-to-day of the intimate connections shown to the audience, usually with casts not exceeding four actors, with apartheid hovering implicitly or explicitly just beyond a village or a small interior until the policy was revoked in 1994 and even beyond.

Because of his status as a white citizen, Fugard was spared the harshest of penalties for his flouting of the restrictive laws, although he was carefully monitored by the government and had his passport revoked, while some of his black collaborators were jailed. In that 2010 interview, Fugard said of this period, when a group of black artists asked him to work with them: “I had a moral responsibility to speak up, to demand attention. They made me aware of my obligation.”

Fugard’s paired plays Sizwe Bansi Is Dead and The Island, the latter drawn from the experiences of actors imprisoned on Robben Island, where Nelson Mandela was incarcerated for 18 years, were created collaboratively by Fugard, Kani and Ntshona, with the latter pair receiving a joint Tony award for best actor in 1975 when the plays reached Broadway. Prior to that, they had played the Royal Court in London, with Sizwe Bansi Is Dead transferring to the West End.

A relationship with the Yale Repertory Theatre in New Haven, Connecticut, beginning in 1980 yielded a new platform for Fugard, with his plays making their US or world premieres there under his direction through much of the decade, including A Lesson from Aloes, ‘Master Harold’… and the Boys, The Road to Mecca and A Place with the Pigs. A revival of a slightly retitled Blood Knot was part of this run as well. Fugard observed that it was his US success that gave him the financial resources to sustain his career, saying that four-fifths of his income derived from the US.

‘Master Harold’ would become perhaps his greatest success and his most autobiographical work. Blending elements from his own upbringing by an embittered alcoholic father and a liberal-minded mother who was the family breadwinner, Fugard took a shameful incident from his own life, when as a 12-year-old he took out his own pain on his surrogate father, a black employee of his mother’s, by spitting in his face. This mournful evocation of the ugliness of apartheid managed to be shocking yet hopeful, and it found favour internationally, including a Tony award for Zakes Mokae and a London Evening Standard award for best play. It was revived recently at the National Theatre in 2019, starring Lucian Msamati.

Continues...

The end of apartheid in 1994 led Fugard to wonder whether his career was over, but it continued, prolifically, as he continued to explore the morality and humanity of life in South Africa in such plays as Valley Song, The Captain’s Tiger and The Train Driver. It was also in this period that Fugard addressed his own alcoholism.

Even though Fugard defined himself primarily as a playwright, saying he acted in and directed his works mostly out of a perceived necessity, he also made occasional acting appearances in films, including Peter Brook’s Meetings with Remarkable Men, Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi and Roland Joffé’s The Killing Fields. He co-directed and co-wrote the film version of The Road to Mecca, reprising his stage role alongside Yvonne Bryceland, who played the central character internationally.

Speaking of apartheid, of ‘Master Harold’, and more broadly of his career, he said: “The lasting effect of those early years and the indoctrination I experienced in South Africa had been very long-lasting. But I have tried, step by step by step, to emancipate myself.”

Harold Athol Lannigan Fugard was born in Middelburg, South Africa, on June 11, 1932, and died on March 8, 2025, in Stellenbosch, South Africa, aged 92. He is survived by his daughter Lisa, from his first marriage to Sheila Meiring, from whom he was divorced in 2015, and his wife Paula Fourie, who he married in 2016, and their two children, Halle and Lannigan.

Latest Obituaries

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99