Amadeus returns to the National Theatre, scene of its original triumph

The patron saint of mediocrity is back. Antonio Salieri returns to the National Theatre to do battle with his arch nemesis Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart in Peter Shaffer’s play Amadeus, 37 years after it was first produced there.

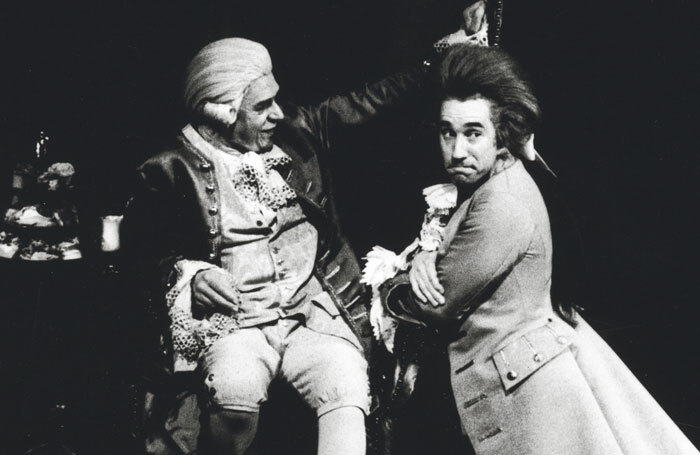

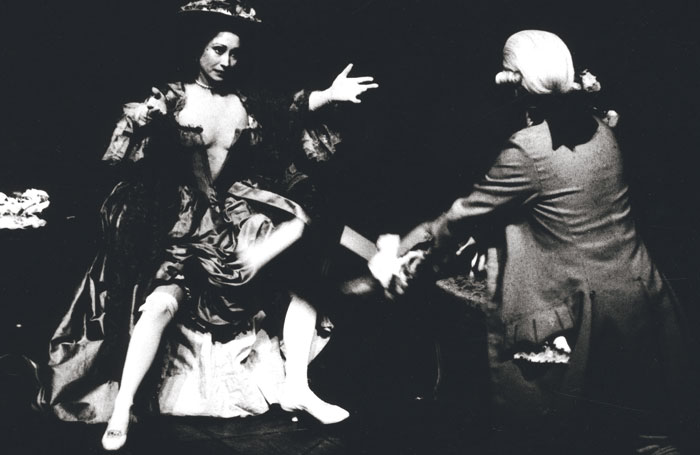

Despite its rather dubious historical provenance, Peter Hall’s 1979 production, starring the great Paul Scofield as Salieri and a 30-year-old Simon Callow as Mozart, stunned critics and audiences alike with its dazzling theatricality, its narrative conceit and, of course, its dramatic use of Mozart’s sublime music. It was by far the National’s biggest box office hit since opening on the South Bank three years earlier.

Shaffer’s masterstroke was to take the clearly documented antipathy between the two composers and deploy artistic licence to suggest that Salieri might have gone so far as to poison the younger man. There is no evidence to this effect. Indeed there is evidence to suggest they were mutually respectful of each other, at least in public.

“The problem with the Mozart-Salieri story is that there is no end,” Shaffer told an American interviewer, “One survived the other by 32 years. It’s not much of a climax is it? There had to be a scene between them, a confrontation. That’s what drama demands.”

It was a scene he rewrote over and over, finally settling on the ravaged Mozart offering the score of his unfinished Requiem Mass to a sinister, masked patron, who turns out to be Salieri.

But why let the truth get in the way of a cracking good yarn? What makes Shaffer’s play a masterpiece is its universality. How often has every one of us encountered a situation in which your own talents or virtues are measured against someone else’s and found wanting? Amadeus is the ultimate expression of that feeling of inadequacy we have all experienced at some time in our lives.

It was also an opportunity to dramatise for the first time the disconnect between Mozart the man – infantile, shrill, vulgar – and Mozart the unsurpassed musical genius. It is not hard to believe that the ultra-refined and courtly Salieri would have found Mozart’s behaviour repugnant.

Reflecting on playing Mozart in the Guardian in 2007, Callow wrote: “As imagined by Shaffer, this Mozart contradicted everything that his music seemed to be. He strutted, preened, shrieked, farted, rutted, burbled, dreamed and finally, after a long and frightening scene with a masked figure he took to be the messenger of death, he died.”

Shaffer’s original choice of director was John Dexter, who had masterminded his two previous successes, The Royal Hunt of the Sun (1964) and Equus (1973), and favoured Christopher Plummer for the role of Salieri. But the sharp-tongued director proved too much for the mild-mannered Shaffer on this occasion, and it fell into the lap of Peter Hall, whose knowledge of Mozart’s work proved useful and opportune.

In an interview in 1992, the playwright praised Hall as “the most patient, calm and imaginative of directors [who] saw very clearly the vision I had, physicalised it, and made it work. He created the most wonderfully elegant-looking production.”

Callow recalls that, at the first reading of the play, after much giggling, shrieking and sobbing, the director put his arm around Callow’s shoulder and said quietly: “That was a very brave performance. But I have to believe at all times that he wrote the overture to The Marriage of Figaro.”

As for acting opposite Scofield, one of the last great titans of the mid-20th-century stage, Callow says he approached the ordeal with “a kind of bliss mingled with dread… acting with him in the rehearsal room was inspiring and paralysing in equal measure. Our relationship was pretty well that of the characters in the play, with the difference that I was playing a genius, while he actually was one.

“When we left the rehearsal room and got into the theatre, I felt him stretching and prowling like a panther in the jungle, sniffing the space out. He seemed, even during technical rehearsals, to be expanding. By the time the audience arrived for the first preview, he seemed like a giant.”

The first preview set the tone for the entire run at the National, and subsequently in the West End, culminating in an ovation “like the roar of the ocean”, in Callow’s words.

Despite his triumph as Salieri, Scofield declined an invitation to repeat his performance on Broadway, opting instead to keep to his promise to Peter Hall to play Othello at the National. A triumph on Broadway would probably have led to Milos Forman casting him in the film version of Amadeus and the chance of winning a second best actor Oscar.

In the event, Ian McKellen took the coveted role on Broadway, winning a Tony award in 1981. Tim Curry played Mozart, with Jane Seymour as his wife, Constanze.

The 1985 film went on to win eight Oscars, including best screenplay for Shaffer, best picture, and best actor for F Murray Abraham as Salieri.

Michael Longhurst’s revival of Amadeus runs at the Olivier, National Theatre, until January 26, 2017

If you’d like to read more stories from the history of entertainment, The Stage Archive offers access to all back issues of the paper from 1880 to 2007 and is available from £15.

Latest Obituaries

More about this organisation

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99