Belarus Free Theatre’s Natalia Kaliada: “Funding can lead to self-censorship” – speech in full

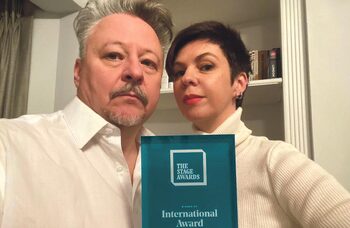

Natalia Kaliada is co-founder of Belarus Free Theatre.

She spoke today at the annual State of the Arts conference No Boundaries 2015. Kalida was addressing the question: “What permissions do we have and where is the line between responsible artistic freedoms and censorship?”

The full transcript of this speech can be found below, or to watch the conference streamed live click here.

It’s exhausting to be free.

I was born behind the Iron Curtain. Leonid Brezhnev died when I was nine years old.

He was the General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party for 18 years.

Everyone in the school cried including children and teachers.

Everyone at home laughed and was happy but told me not to talk about that when I was at school because we were still in the Soviet Union.Almost 10 years later, when I started university, the Soviet Union finally collapsed. There were four golden years of an independent Belarus. Those years are long ago.

For the last 21 years, the country where I was born, has been under a dictatorship.

When I was released from jail after a short detention by the Belarusian police, my grandmother whose husband, my grandfather, had been imprisoned by Stalin, told me that she never thought I would be in the same trouble as previous generations of our family.

How far I can push boundaries? “As far as needed to be free”. This is what my parents taught me.We established Belarus Free Theatre under a dictatorship.

We picked a day and announced the existence of Belarus Free Theatre.

We had no building and no funding besides our own money.

We didn’t exist for the authorities of our country but existed for the people of our country and for the outside world.

We went to people and asked for donations.

In our apartment in Minsk, we printed out flyers and put our phone numbers on them. We went to each and every university, and glued our flyers up in the toilet stalls so that every student would see them. This is how we started to build our audience. It’s a good marketing tip, if anyone needs it.

We had four central aims:Number one – to help young people understand that the system fears educated young people who want to change society through their art. We wanted to help them reject the fear imposed on them by the authorities.

Number two – to get the artists who had been blacklisted in Belarus back to our country and to our people.

Three – to create shows that address every single taboo that exists within us and within our society, and in doing so, to create a space where audiences understand that there is a place where people aren’t afraid to talk honestly about themselves and what is happening around them.

Fourth, and above all – to defend human rights – at all costs.—

The whole world mistakenly thought that when the Soviet Union collapsed there would be no more artists who would be punished by the system for speaking freely and loudly through their art. No more Brodsky, Baryshnikov, Tarkovsky, Solzhenitsyn, Rastropovich.

Slowly but firmly the whole culture of supporting dissidents in the west started to vanish. Even the words ‘artists’ and ‘dissidents’ started to be replaced with the word ‘refugees’. Critics loved the artists who came to perform in their countries when they were considered ‘victims’ coming from ‘exotic dictatorships’ but once those ‘victims’ started to talk about issues that existed in their new homelands, admiration and love was replaced with what I see as «self-defence». From within the creative industries within democratic countries boundaries began to emerge – begging the question, who is allowed to say what from the stage?As people who come from the Last Dictatorship in Europe, we are highly sensitive to any form of control. We understand that censorship under a dictatorship is imposed by the external ruling regime. Censorship from within a democracy is often self-imposed by the individual; the fear of crossing invisible boundary lines comes from within.

Creative conformism is blooming in democratic countries and so you have to ask whether the only way to secure funding today is to create safe art?

How many Shakespeare plays are staged in London every year?

How many Chekhov plays are staged in Moscow every year?

These two writers were highly critical of their own society and yet today they are considered ‘safe choices’ for theatres, for audiences who can’t be disturbed or provoked and what is more, for funders who want to support only what is safe for their strategies.Like the NHS, the culture industry has more managers than creators. Managers need to follow the guidelines of trusts and foundations, to meet marketing targets, to present outcomes and outputs. It can feel like a complex and sometimes obscure system that requires people not just to have a background in the arts but in management, marketing, economics. With fewer young people than we might think going to university, and universities themselves becoming increasingly defined by market prerogatives and less by experimentalism and free enquiry, this may become a two-fold barrier in itself. It’s a gate-keeping system that disadvantages emerging artists, especially those who perhaps don’t have the opportunity to go on to supposedly rarefied modes of higher education.

Worse still, is it just becoming a word game? To use the latest buzz words: mobility, cultural dialogue, digital strategy, outcome, output, development strategy, audience development, outreach, cultural innovation – all in order to get funding. When words and meaning become alienated from each other, nothing could be further from the artistic process.

—

No boundaries exist for me when I get on Skype to work with actors and students underground in Minsk.

No boundaries exist for me when I contact Ai Wei Wei who was under house arrest in China and ask him to create a symbol for us, artists who are refugees from the own country in the UK.

There are no boundaries for artists and there are no boundaries between artists.

But there are boundaries between artists and the funding system, and this can lead to self-censorship.—

Belarus Free Theatre are often invited to different countries to create shows about the taboos that exist within these different countries. Almost every time, we are told that we are the only ones who can do it because we are from a dictatorship and therefore we can say whatever we want. Theatres around the world are afraid for their artists to say the unsayable because they are afraid they will lose their funding.

I paid the price, and my family paid the price, for speaking our minds freely whilst living under a dictatorship. Now, living in a democracy, I start to develop a fear of speaking freely in our shows in case we will lose our funding. Very often I am told that it’s better not raise one topic or another, such as fracking or nuclear power, for example.

Even the title of this session – responsible artistic freedoms – has a note of censorship within it because the notion of responsible is subjective.

When Harold Pinter was in front of protests in support of the Kurdish people or when Josef Brodsky forcefully rejected his Soviet citizenship, they didn’t think of whether it was responsible or not?They pushed against those boundaries imposed by different regimes in different countries with an understanding of how important it was that all wars, conflicts, financial crisis take place in their own back yard, irrespectively of whether it was in fact somebody’s else backyard.

“Artists are responsible to defend freedoms and fight censorship”. I believe that when artists create great art, and that art is then observed by more and more people, their responsibility to defend the freedoms of others in both their own and in different societies becomes greater and greater.

—

If we had thought that it was not responsible to push boundaries living under a dictatorship, there would be no Belarus Free Theatre today.

Under dictatorship, we can’t talk about suicide, mental health issues – not to mention political kidnappings and murders, torture and imprisonment.

The dictator who runs Belarus, and has done so for the past 21 years, thinks that it’s better to be a dictator than to be gay.

Is it worth of pushing against these boundaries and being called ‘Enemies of the State’?Yes it is.

And it’s worth pushing those boundaries even further and continuing to create art in the form you believe in, even if it leads to you being smuggled out of Belarus and becoming a political refugee?

Yes it’s worth it even though you are considered to be stateless, humiliated by the UK Border Control who ask for your fingers prints every single time you come back to your adopted home.

All of it is worth it – if, and only if – we are able to continue to create shows that we could create underground in Belarus knowing that we might be raided, arrested, beaten up for the things we say on stage.

There, we knew that nobody could control us so far as to deciding what could and couldn’t be said, what topic it might be better not to include in order not to lose future funding.

We went underground knowing that it was the space where we could expand deeper and deeper in order not to have any boundaries around what we create.

We rehearse and perform in apartments, houses, cafes, restaurants, clubs, forests and woods in Belarus. Our own money, this box, and our touring to more than 30 countries in five continents has given us a chance to create what we wanted.The major question that is hanging in air now: do we need to go underground in London in order to continue to create shows that we feel need to exist for world politicians to understand that we are watching them no matter where we are: in Belarus, Rwanda, Uganda, Australia, or the UK – and that we can make free art with no fear of losing funding? Is it possible?

Must artists live through revolutions, wars, dictatorships in order to be free from self-censorship?

Are people who live under dictatorship and create art free-er than people who live within a democracy?

For those artists who live under tyranny and dictatorship, the price of freedom of artistic expression can be as high as their life – but here in a democracy we might say it can be measured in pounds and pence.

—

Our patron Vaclav Havel once told us that if you want to prolong the existence of the regime that you have now, you continue to whisper, if you want to stop it and change it, you need to scream.

We hear the shouts and screams of artists from Iran, Syria, Russia, India, Ukraine, Belarus when their human rights are violated, but nothing but silence in the UK when there are signs of censorship. Why is there so much fear to stand up for provocative artistic work in cities across the UK?

This is what I feel is missing now in our second home, a united call out of British artists in support of their own artistic freedoms. If we act together, as artists standing together in defence of these freedoms, there will be no possibility for funders to withdraw their support. The arts are the pride of this country and a huge economic force in their own right. We should use this power together to defend hard won freedoms.

—When we were smuggled out of Belarus ten years ago, our youngest daughter was on the run with us and missed school for 10 months. We couldn’t leave her in school. The KGB were looking to take her from us and to send her to an orphanage to silence us.

She was happy to be out of school for 10 months. I was really upset about that and about the price our children paid for our action. But it’s good to have a wise husband who said that her travelling with us and watching shows would give her more than any education.

Ten months later she rejoined the school, and this year she got her GSCE’s with all A and A stars.

Sometimes I think that 10 months of experiencing art every day in different parts of the world gave her more that all her previous years in school.The school that she attended in Belarus broadcast long speeches from the Dictator whilst he was removing the best writers, philosophers, historians from the educational curicculum in Belarus. The dictator knows that with no arts and culture, history will be easily re-written.

Now my two daughters go to schools in London.

This country became our second home because of the people who live here who took care of us and gave us places to live and work. I am so happy that when they go to school in London, real subjects are not replaced with long speeches of David Cameron.

But I don’t want to see how my children begin to understand that arts subjects are not taken seriously in schools here as even they know from their own past experience in Minsk what it’s like when the arts are systematically removed from their educational system.

Contemporary artists can’t avoid talking about politics, the moment they do, they stop being contemporary and very soon they stop being artists.

We didn’t vanish under a dictatorship and we don’t plan to vanish within a democracy.

More about this organisation

Production News

More about this organisation

Production News

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99