Rage against the machine: Is AI in performance an opportunity or a threat?

Theo Bosanquet

Theo BosanquetIs artificial intelligence in performance an opportunity or existential threat? Theo Bosanquet meets the people investigating this technology, from theatre practitioners to academics, to try and find some answers

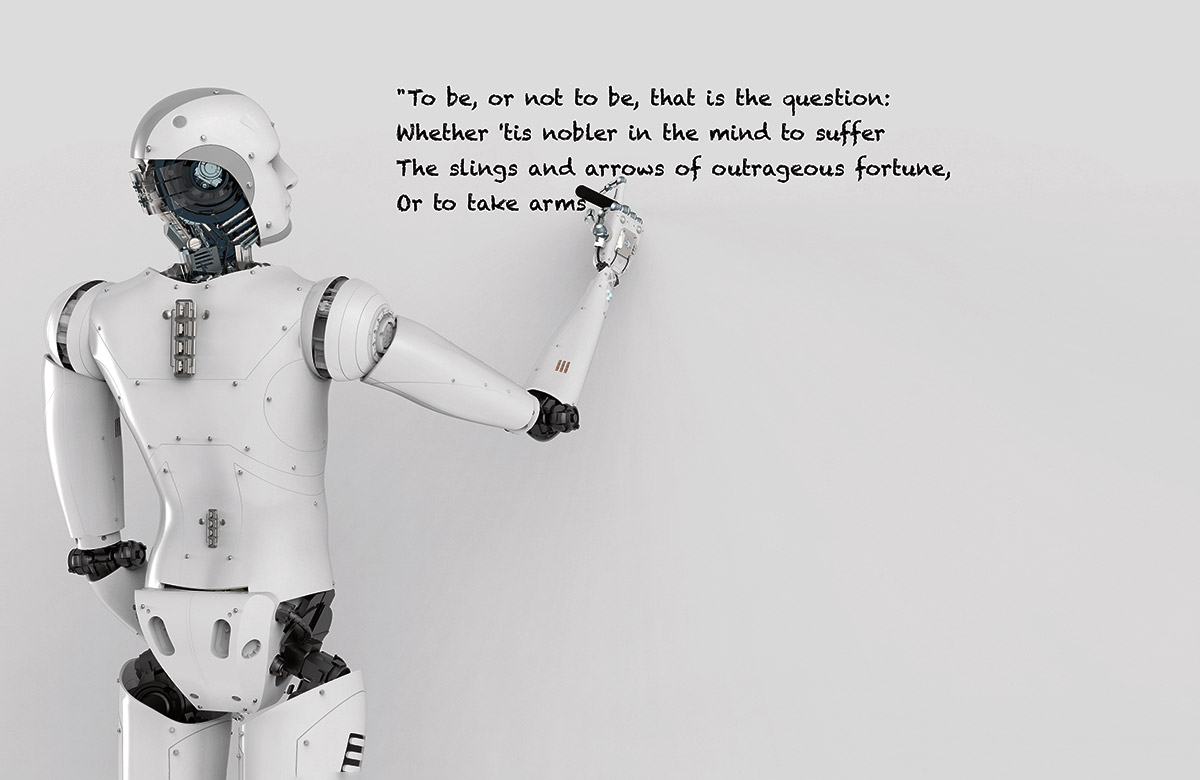

When thinking about artificial intelligence and what it means for actors and other creatives in the future, it’s all too easy to slip into dystopian cliché. The notion of hologram performers displacing real people on stage, audiobooks being narrated by robots, or ‘deepfake’ clones appearing in Netflix series can feel a little alarmist. And yet, all of these scenarios have come to pass, to varying degrees, in recent years. Equity is concerned enough to have released a pointedly titled report, Stop AI Stealing the Show, which argues that unless change is soon made at a legal level, performers’ livelihoods are under increasing existential threat.

So, what is the nature of this threat? What will the future actually look like? And could AI really be the biggest source of disruption to the performing arts industry since the dawn of film?

To begin with, it seems important to define what we mean by artificial intelligence. After all, it is a term that was rarely spoken outside of a science-fiction context until the recent past. Essentially, it means machine learning, but in a performance context this can take many forms. AI systems currently in use include automated voice machines, programmes that can write plays, and robots that can dance (more on these later).

Mhairi Aitken is an ethics fellow at the Alan Turing Institute. She recently performed a stand-up show at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe on the subject of AI, titled Will Killer Robots Save Humanity?. “Recently there’s been a lot of exciting arts projects involving AI, and some of these are really interesting,” she says. “But in all these examples it’s important to note that the AI is not the source of creativity or artistry – that remains the role of humans who are choosing how the AI is used.”

Testing boundaries

Aitken says that, at least for the time being, AI is mainly used as a tool rather than in an authorial sense. “The AI can only do what it is programmed to do, and in that sense it is not so different from having puppets – albeit quite sophisticated ones – within a show.”

But some productions are beginning to test these boundaries. A prominent example was last year’s experimental play AI, at London’s Young Vic. It was prompted by an article in the Guardian written by a programme called GPT-3, under the provocative headline: ‘A robot wrote this entire article. Are you scared yet, human?’

“Kwame [Kwei-Armah, Young Vic artistic director] brought the idea to me and we thought we would try to answer it live in front of an audience over three consecutive nights,” explains director Jennifer Tang. “The initial thinking was that we would try to write around 10 minutes of material live each night, so that by the end of the experiment we would have a 30-minute short play.”

She brought in two playwrights – Chinonyerem Odimba and Nina Segal – to work alongside the machine, and says the results were illuminating. “As we grappled with the system and learned how to engineer prompts that elicited the most useful responses, it became clear that the more interesting question we should be exploring was: ‘How do we – human collaborators – work with AI to write a play?’ So we geared the three evenings to try and unpack that question.”

Did she find the machine’s output to be a match for the humans? “Yes and no,” says Tang. “We found it really easy to dismiss the content it generated with a cursory glance if it didn’t quickly and easily fit with what we thought was ‘good’ or ‘human standard’… However, we found that if we persevered with some of this ‘bad’ stuff and worked at it and tried to make sense of it, we could get past that initial reaction of: ‘This is trash’.”

Continues...

The legal picture

Despite its current limitations, concerns about the capacity of AI to one day displace artists persist. Screen and voice-over work has so far been the most visibly affected, often involving the ‘cloning’ of real-world stars: see the resurrection of Carrie Fisher in Star Wars or James Dean in the case of controversial proposals for the yet-to-be-released Finding Jack.

Equity’s report gives the example of Canadian voice actor Bev Standing, who last year opened a lawsuit against TikTok’s parent company ByteDance alleging that her voice, originally recorded as translation for the Chinese Institute of Acoustics, had been cloned and used without her consent for TikTok’s text-to-speech feature. ByteDance agreed to settle the lawsuit.

Equity general secretary Paul W Fleming says these examples are indicative of a growing trend, which prompted the union to take action. “[AI] is something that is increasingly affecting members and we feel we’re at a critical juncture. We are doing good stuff through our collective agreements in terms of protecting people against the exploitation of AI, but without a mature legislative framework, this is very quickly going to go south.”

Among the changes Equity is calling for is the introduction of stricter image rights for performers to protect them against elements such as deepfake impersonations – AI-generated video and audio that appears to be a real person. “There is a very deep anxiety around ownership of intellectual rights and moral rights around performances,” says Fleming. “What happens, for example, to the ownership of your performance when you’re dead and it’s resurrected and amended?”

Elena Cooper, a fellow at Glasgow University’s UK Copyright and Creative Economy Centre (CREATe), is an expert in copyright history. She says Equity is right to highlight what amounts to a legal lag. “The UK is generally thought of as offering quite strong intellectual property protection, but this is one area where there is known to be a gap.”

Cooper cites the examples of racing driver Eddie Irvine, who won damages against radio station TalkSport for using a doctored image of him in a promotion campaign, and the singer Rihanna, who successfully sued Topshop for selling T shirts displaying her likeness. But Cooper says these individuals only won because the use of their image falsely suggested their endorsement. Things get murkier when it comes to artistic usage.

Equity’s proposals are for more comprehensive image rights, which, while thought to be new in the UK, Cooper’s research shows that, in fact, they have a UK precedent thanks to the way magistrates applied photographic copyright laws in the 19th century as primarily protecting the sitter.

However, “the conundrum of intellectual property is how you define what is protected”, she adds. “We have quite a sophisticated understanding of what this means when it comes to, say, a literary work, but how do you do this for someone’s image or voice? As reproduction gets easier with new technology, this has now become an urgent question.”

Continues...

‘[When it comes to exploring the possibilities of AI], there’s some genuinely exciting work to be done, and there isn’t enough of it happening’ – Adrienne Hart, choreographer and artistic director of Neon Dance

‘Recently there’s been a lot of arts projects involving AI, but the source of artistry remains the role of humans who are choosing how the AI is used’ – Mhairi Aitken, ethics fellow at the Alan Turing Institute

‘[Let’s think] about how these technologies become tools that help human creators become more innovative, more prolific, more visionary’ – Director Jennifer Tang

‘The UK is generally thought of as offering strong intellectual property protection, but this is one area where there is a gap’ – Elena Cooper, UK Copyright and Creative Economy Centre, Glasgow University

‘[Artificial intelligence] is increasingly affecting members; we feel we’re at a critical juncture’ – Equity general secretary Paul W Fleming

’I’m not interested in [AI] replacing actors – for me, the exciting bit is bringing performers into that process’ – Director and writer Kirsty Housley

Artistic potential

It seems clear the legal implications of AI technology are both pressing and convoluted. But what about its artistic potential? One production exploring this question is Prehension Blooms, a collaboration between Neon Dance and Bristol Robotics Lab.

The show tours venues including Bristol Beacon, the Place and Artsdepot this autumn, before visiting Japan in November. It features two human dancers alongside three “bio-inspired robots”, and aims to explore the “nature of companionship and loneliness”.

Choreographer and director Adrienne Hart says the idea sprang from time she spent working in remote areas of Japan. She wanted to make a work that “could have audience members joining remotely in a way that wasn’t just a rubbish version of the live experience”.

The resulting show took more than a year to develop. The robots it uses are “evocative of fossils or prehistoric creatures”, explains Hart, “and move around in sand during the performance… they don’t look like the robots you might typically imagine”. The robots use machine learning to respond to the other dancers, the audience and their surroundings, and one of them can be operated remotely.

On the question of whether robots are displacing human artists, Hart says she can see “arguments in both directions”, but points out that “person-to-person connection” is “fundamental” to live performance, as well as the fact that “all these algorithms rely on human innovation and hard work”.

However, those algorithms themselves are the subject of intense debate. A common criticism of AI in any form is that it is prone to echoing baked-in prejudices. Some say it is inherently sexist and racist, for example, in reflection of these wider trends in society.

Director, writer and dramaturg Kirsty Housley is one of several digital fellows working at the Royal Shakespeare Company to explore how new technologies could shape the theatre of the future. Her credits include co-directing Complicité’s binaural sound piece The Encounter, with Simon McBurney, for which she jointly won The Stage Award for Innovation in 2017.

At the RSC, she is specialising in the future of AI and has a particular interest in the gender politics of AI voice algorithms. She points out the fact that voice assistants (like Siri and Alexa) are majority female, whereas GPS navigation instructions are often voiced by a male. “They did some studies into this and it’s because people don’t like being told what to do by a woman. Technology companies listen to this bias and then incorporate it. So the tech itself is not sexist, but the people who are programming it are.”

Housley emphasises she is not “anti-tech”, and is keen to find more “joyful” applications of AI. She gives the example of a programme that can sample audience voices and create a composition based on them. “It will be a different piece of music every evening and you can control your own level of input. It’s really interesting in a performance context.”

She is upbeat when it comes to the technology existing alongside human artists in the future, rather than displacing them, comparing it to the evolution of microphones.

“I remember everyone being concerned about what mics would do to vocal projection. It just changes our style. I’m not interested in [AI] replacing actors – for me, the exciting bit is bringing performers into that process.”

Hart echoes this sentiment, calling for more artists to “enter labs” to explore the possibilities of AI. “I think there’s some genuinely exciting work to be done, and there isn’t enough of it happening.”

So, what does the future of AI in live performance look like? While it may be difficult to filter out Black Mirror-esque dystopian ideas, even sceptics agree that it is unlikely to ever displace humans entirely.

L Nicol Cabe, who wrote and performed the show Effing Robots: How I Taught the AI to Stop Worrying and Love Humans, which was based on her experience with chatbots, says there are limits to its sophistication.

“As [AI] works now, it is not a galaxy brain or deep-mind solution to all problems that will fully eliminate some types of work or vocation… It’s like a different genre, which we as human beings can curate and manage to tell the stories we want.”

She says she is “not worried about it replacing [her]” as an artist, but concedes there “will certainly be attempts to replace humans” in other fields.

Equity’s Fleming points out there are opportunities provided by the technology, alongside threats. “Artificial intelligence requires skills that our members are trained in. Our members are the step in the middle of whatever AI technology you’re talking about… But they need to be paid and credited properly for it. And that is not a new battle, that is an age old conversation.”

Continues...

Period of adjustment

As with the advent of all new technologies, there is bound to be a period of adjustment. But most people I speak to agree that the ‘artificial’ aspect of AI will always be its limiting factor. As Housley puts it: “AI is not going to provide the next Shakespeare.”

“My hunch is that AI will probably lag behind other technologies in theatremaking,” says Tang, citing virtual and augmented reality as examples. “But I think AI can be part of that suite of technologies that we use in the creation process, and which should be enhancing and complementing the theatrical experience, rather than replacing it. For me, we should be thinking about how these technologies become tools that help human creators to become more innovative, more prolific, more visionary. If we can think about them as tools to enable and facilitate human creativity rather than completely replace us, then perhaps there could be [an] increased appetite to embrace them in our processes.”

There is also the limiting factor of finances. AI technology, after all, doesn’t come cheap. Producers of the recent Abba show Voyage, which features digital avatars of the band in their heyday, said the show would need to recoup £140 million just to cover the costs of making it. “[This technology] isn’t getting cheaper any time soon,” says Housley. “To get into this stuff you need a big organisational structure behind you to forge those collaborations with tech companies.”

On whatever scale it’s used, AI’s role in the performance landscape looks set to grow and, as we have seen within our everyday lives, it is a technology that can quickly become integral. What that means for the industry’s workforce both on and off stage is a question that will only get more pressing.

Prehension Blooms tours to Bristol and London from September 28-October 21. Details at: neondance.org

Long Reads

Recommended for you

Opinion

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99