Kultur club: How Germany has led the way in supporting the arts in lockdown

Germany has been praised for its fast response to coronavirus, having pledged billions in aid to support the country’s cultural sector. But, as ITI Germany director Thomas Engel tells Nick Awde, there are still issues to address, including a lack of clarity on how the creative industries will reopen across the country’s 16 states and the need for a dedicated culture ministry

On Sunday night, the UK government announced a £1.57 billion emergency package for the arts. This comes after other European countries have already responded to help protect their cultural sectors, with many pointing to Germany as the standard bearer in backing for its arts.

A comparison with other countries is not as simple as it seems though. Every nation has different systems and structures that bring their own strengths and weaknesses, and don’t always respond positively, no matter how much money is thrown at them.

The German theatre system has always tended to be lionised, an image boosted in the UK by the Berlin theatre weekenders and a healthy respect for the country’s unwavering financial support for culture. But, the reality of its coronavirus crisis response is a bit more complex.

Culture in Germany is officially protected and enjoys constitutional status within its 16 states – the national Basic Law protects artistic freedom. Arts funding is supported at every level: federal, state and municipal (note that Berlin operates at state level). It is a ‘mid-heavy’ system, where direct national funding tends to go to institutions and projects of nationwide significance, and independent foundations, such as the Federal Culture Foundation and the Foundation for Performing Arts, while the states and municipalities drive everything else. It’s an impressive system, with few cracks to fall through.

In short, theatres are divided into state (fully subsidised with permanent buildings and ensembles), semi-independent (partly subsidised) or independent (commercial), operating in a cultural landscape dominated by museums, architecture, the visual arts and public events, which also get the lion’s share of funding and rescue packages. It’s a system in line with the rest of continental Europe – where the performing arts sectors have all been halted in the same way by coronavirus.

Germany’s financial aid package

Where Germany differs is in the immediacy and scale of its response to the crisis. At the beginning of June, it rolled out a €50 billion package aimed at freelancers and small businesses including the arts and culture industries. This was distributed within four days of the announcement and forms part of an overall €750 billion in aid announced in March. The Berlin Senate has offered €100 million in €5,000 grants to freelance workers and small businesses in the cultural sector.

Social security for freelancers has been guaranteed for a period of six months including housing, so that “everyone can stay in their own home”, while the country has been praised on all sides for its furlough system, which pays 60% (67% for those with children) after-tax earnings. Crucially, unlike the UK, Germans are encouraged to work part-time, which reduces the cost of a system road-tested during the recession after the 2008 global financial crisis.

The first counter-crisis measures in March included short-term compensation for contracted artists, direct support for freelancers up to €15,000 as a one-off payment, and shifting of grants and funding fully or partly to next year. A new bailout package starts in July of €130 billion, which has €1 billion earmarked for the culture industry for 2020 and 2021.

However, there is growing concern that these funds are aimed at cultural entities and not individual practitioners, a situation complicated by recent shifts in the business model, says Thomas Engel, director of the Berlin-based German Centre of the International Theatre Institute which awards its Theater der Welt international festival to a German city every three years (the May 2020 edition now postponed until June 2021).

“Within the last 10 to 15 years, many municipal theatres changed their administration model from governmental/municipal accounting to public-private business companies,” says Engel. “This meant far greater dependency from box office, touring, project funding and sponsorship. Theatres with greater dependency from box office (up to 25% from 11-13% before) receive no compensation for loss of incomeduring lockdown.”

Theatres not fully under the state financial system therefore are at very high risk because they have to earn much more than those that are 100% covered and can pay salaries. However, this is unlikely to result in a wave of crisis-related bankruptcies since affected theatres can apply, like private theatres or general businesses, for support in the shape of tax deferments, loans and subsidies. The shift in model has also contributed to the growing number of freelancers in Germany who have no assets or reserves, and for whom the shutting down of public live, film and studio work, even rehearsals, means an end to earned income.

The safety net for everyone in the country’s theatre industry is wider and more supportive than anywhere else in the world. But coordinating the nationwide opening up of the industry is not proving to be as straightforward as keeping a holding pattern to ensure no one slips through the net.

“A lot of institutions and theatres, as well as the funders at the ministries, are having a hard time,” says Engel. “Even though we have the new packages and programmes running, there are no administrative human resources behind it. We also have the challenge of meeting all kinds of regulations that don’t exist yet.”

A history of helping

Injecting a huge amount of money into the system to help society isn’t new to Germany. It happened with the 2008 crisis, and, as a more positive response, with the federal government launch in 2013 of ‘Kultur Macht Stark’ (Culture Makes You Strong), a national cultural education campaign that made a large budget available for theatres, especially the independents, as part of an initiative to ‘power up’ society.

Under the brand of Kultur Macht Stark – which is still running – the idea was to create new programmes, especially in the performing arts but also the visual arts, with the aim of developing new audiences by empowering poor and marginalised families and refugees through access to cultural education in order to improve their connection with society and their role in it.

But it wasn’t plain sailing, says Engel. “Most of the funding was carried over from the ministry of economy and the agency for air and space traffic, which then was responsible for the administration (the agency is the umbrella organisation for one of Germany’s largest project management agencies). And, of course, the economy sector runs totally differently to the cultural sector, so it was really hard to implement.”

Things improved, but only after major opposition and negotiations with the government to rebalance distributing the programme and to make it accessible, especially for the freelancers and self-employed within the cultural sector.

“Now the problem is tenfold,” says Engel, “because every state seems to have its own rules for reopening culture. We also have national standards which are sometimes binding, sometimes not. So, culture and education are at present a patchwork where artists in some states have totally different conditions than are found in other states.

“So, we just follow the news every day as the conditions change. There will be a strong opening up, then a sudden return of the virus that closes down certain areas or makes you avoid them. Yes, some schedules for the new season after the summer have been announced, but it’s clear that these are the organisations that are in a strong position financially.

“I have a lot of feedback from theatre managers who are on a permanent alarm situation from week to week – how to survive the next month, to schedule rehearsals, what is needed to plan the next performance, the audience numbers you can count on, and so on.”

‘A lot of institutions and theatres, as well as the funders at the ministries, are having a hard time’ – ITI Germany director Thomas Engel

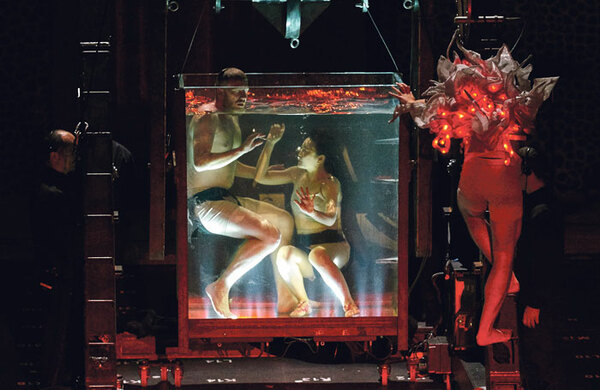

The date for reopening theatres and venues is mooted from September onwards, but performances face balancing the full cost of production with audiences limited to 40% to 50% capacity, a 75-minute cap before they have to change the air, and current social distancing limits of 1.5 metres. Typical of the first league venues is Berlin’s Schaubühne, which has been successfully streaming top productions and related talks, and now plans to reopen in October, playing it safe with a solo version of Peer Gynt by Lars Eidinger and a monologue by director Milo Rau.

A further positive reaction is that the networks and organisations for independent artists are lobbying prominently and a lot of support systems have been readjusted as a result to accommodate freelancers and the self-employed. For example, institutions with secure finances are encouraged to support their independent partners by paying for contracts which aren’t able to be fulfilled yet. As crunch time for reopening approaches, the lobbying remains critical because of the enormous number of freelance and self-employed practitioners in the sector.

When things do start to reopen, should there be a second wave or local outbreaks of coronavirus, as has already happened in Berlin and the meat processing plant in Gütersloh, theatres may well find audiences will stay away.

Even festivals, which are a big draw for foreign visitors and a significant part of the tourism economy, aren’t being scheduled for the summer. Whether they are open-air or covered, factors such as square metres for social distancing still apply and, for most events, it simply makes no sense to organise a festival because it’s too expensive to comply.

“If we’re talking about the culture tourists who go around to festivals, well, the summer festival season in Germany is gone. And if there are plans for festivals usually scheduled for autumn, they’re not certain either. To prevent a second wave, we need to prolong the protective measures up to some point in late autumn, which gets us into the traditional flu season and the threat of coronavirus, so it is difficult to sell,” Engel says.

The summer festivals represent a huge chunk of seasonal employment, and technical and backstage workers are especially hard-hit, being mostly freelancers and independent companies. They have now started public protests around the country, symbolically projecting red lights on public buildings.

Pivoting to digital

One area where support has helped things to develop is online, where packages have stimulated a mixture of physical and digital offers. But, says Engel: “Everything had to be rethought this way anyway. It’s not wrong, of course, but it does pressurise the whole performing arts sector into a kind of data-driven economy, which brings a whole new set of challenges.

“If you sell your productions on models such as live streaming, you become part of another system. Broadcasting live performance is a part of broadcasting, which is a worldwide economy system with conditions that are totally different from going to your publicly funded local theatre to see a show.”

Nevertheless, the lockdown has produced a united effort across the nation’s theatres to develop digital avenues to retain audiences and to improve the experience. A temporary copyright agreement with Germany’s strict copyright agencies has created a 48-hour waiver for audiovisual material via the web. Normally, all rights for internet broadcasting need to be negiotiated separately from all the companies and individuals involved in a production, but the new rule removes its classification as internet broadcast and so permits free access for users.

“We are now actively working on creating an environment that is not just 48 hours of free access but tied to real production timing – in the evening, one and a half to two hours, access limited through the purchase of tickets,” says Engel.

The first experiments already look promising, he adds, although this is not a substitute for live performance in the long run but could be a permanent addition for some companies. Logically, it has been the independent smaller venues who were the first to try to keep their audiences via digital format. The big theatres have far less pressure to do this, despite high-profile venues like the Schaubühne unveiling its enviable back catalogue.

One major plus in the focus on reopening theatres in Germany is the strong arts lobby, especially from the independent organisations. They do a good job, says Engel, and are organised in their own chapters within each state and on a national level.

The need for a dedicated culture ministry

“The difference between the cultural politics of Germany and many countries in Europe can be found in the structure of how Germany is organised,” says Tobias Biancone, ITI’s director general in Shanghai.

“In Germany, the cultural politics are given to the 16 members of the federal republic, whereas in France, for example, it is mainly the national government that has the main authority, even for culture. In Germany, the authorities, backed by civil society and foundations, have a much broader remit for culture and the arts and thus a broader distribution of financial support is possible. Moreover, Germany has a stronger economic system, which allows the constituent states of the federation to spend more money on culture, even in the times of the Covid-19 pandemic.”

A particularly powerful ally is the German Cultural Council (Deutscher Kulturrat), the umbrella organisation of German cultural associations, which compiles a ‘Cultural Red List’ to publicise threatened or closed cultural institutions such as theatres, museums and other cultural buildings.

“These organisations combine to have a very strong voice and position on the arts, especially now, and the German Cultural Council is in very close contact, even conflict, with the ministry of culture, which is not a ministry.”

Not a ministry? It comes as a shock to discover that Germany operates a system for supporting culture and media on a non-ministerial basis – because indeed there is no cultural ministry. What coronavirus has done is to highlight the need for a functioning federal ministry of culture that can support and coordinate on a meaningful national scale.

Monika Grütters is the longstanding commissioner/minister for culture and the media, who oversaw increasing the overall budget for federal cultural affairs by more than 30% – up to €1.67 billion – between 2013 and 2018. In March this year, she was quick to reassure the country that “artists are not only indispensable, but also vital, especially now”. Technically, however, chancellor Angela Merkel is the federal culture minister responsible for implementing cultural policies.

The lack of clarity over reopening, much of which stems precisely from that lack of a dedicated ministry, means that pressure is still needed to ensure the government’s focus. As Olaf Zimmermann, director of the German Cultural Council, told German broadcaster Deutsche Welle: “It has to be extracted from the chancellor’s office and to get its own structure that will integrate the cultural issues that are currently handled by the ministries of foreign affairs, economy and the interior.”

Meanwhile, the various national and local chapters of arts organisations are forced to negotiate with their local governments, a process made more difficult because human resources at a local level are far weaker than they are nationally.

“But it’s definitely better than it was before,” says Engel. “There’s a strong will towards establishing a strong and constructive dialogue at policy level and I would say there is an enormous drive now for the remaining islands of public arts and culture to become a true part of the whole cultural economy system.

“I hope it would remain like this, but of course everybody knows that a lot of things are running parallel and we will only see how they join up in the next year. Cuts are very likely in the budget of the regions and cities bearing the most support for the arts, where the government isn’t really there.

“But there is a big consciousness in Germany to keep culture in a strong position, and that it needs to be supported by public funding. It’s about [protecting] culture... from market forces, [and ensuring] our institutions and cultural workers are able to work and thrive.”

Theater der Welt international festival has been postponed to June 2021. Details: theaterderwelt.de

Long Reads

Recommended for you

Opinion

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99