Four nations, 20 shows: what did I learn about the state of UK theatre today?

Alistair Smith

Alistair SmithAlistair Smith is editor of The Stage. He is also the author of two major industry reports (the London Theatre Report and the Theatre W ...full bio

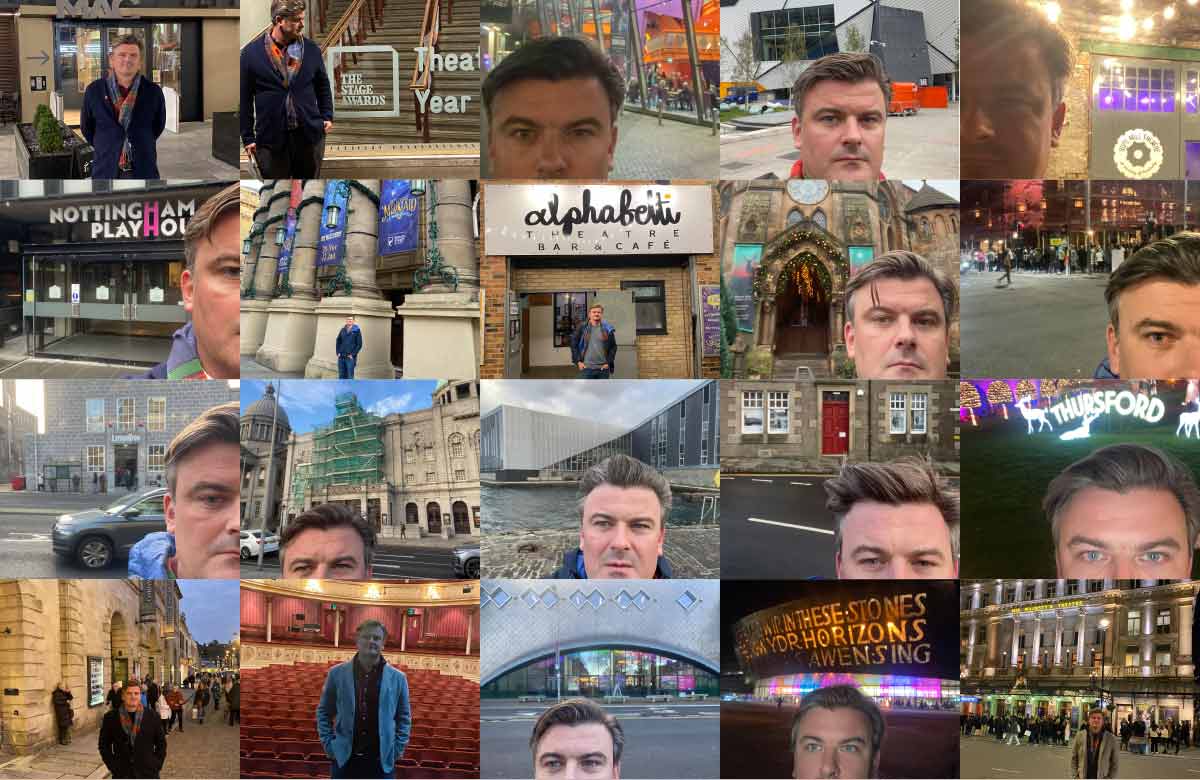

After 20 years at The Stage, and two decades after theatre’s funding taps were turned off, editor Alistair Smith embarked on a tour from the tip to the toe of the United Kingdom, taking in productions across the four nations and speaking to those behind them, to discover how this period has shaped the industry we see today

Alistair Smith is editor of The Stage. He is also the author of two major industry reports (the London Theatre Report and the Theatre W ...full bio

John Tusa, managing director of the Barbican Centre, called it a “slap in the face”. Michael Grandage, artistic director of the Donmar Warehouse, warned that previous gains made by the UK theatre sector “have now the potential to unravel”. Equity’s general secretary Ian McGarry went even further, describing it as a “breach of faith” and accusing the Labour government of “empty promises”.

Twenty years ago marked a turning point for the arts in the UK. And not a good one.

After New Labour came to power in 1997 with its Cool Britannia vibes, there had been a steady increase in the amount of money that the UK government spent on the arts.

This included, in 2001, a £70 million cash injection into the theatre sector that saved much of the country’s crumbling regional infrastructure from disaster.

But December 2004 – 20 years ago this month – marked the first time since Tony Blair had come to power that the taps started to be turned off. Funding in England was frozen at its 2005 level of £413 million until 2008.

The reaction at the time, as you can see from the selection of quotes above, was furious.

£341m

Box-office returns in the West End in 2004, with audiences of around 12 million

£893m

Box-office returns in the West End in 2022, with audiences of around 16.4 million

This was the backdrop that coincided with my first few months as a junior reporter at The Stage. Indeed, as well as marking the first Budget by a Labour government since 2010, the end of October 2024 marked my 20th anniversary on staff at this publication.

The two decades I have spent writing about UK theatre have seen many, many changes. I have witnessed multiple transitions of government, seven new prime ministers (including a shift to Conservative-led rule from 2010 and back to Labour this year) and countless culture secretaries, the 2007-08 financial crisis, the London Olympics in 2012, Brexit and the Covid pandemic.

The two decades have also, it should be said, been a period of remarkable growth for the commercial theatre sector.

Box-office returns in the West End rose from £341 million in 2004 (with audiences of around 12 million) to £893 million in 2022 (with audiences of 16.4 million). This was helped, at least in part, by the advent of Theatre Tax Relief, first introduced by the Tory government in 2014.

What the period has not seen is any increase in arts funding and, while the pattern of funding cuts has not been identical across all four UK nations, the direction of travel has ultimately been the same: downwards.

Today’s theatre sector is very different from its incarnation in 2004 and the years that immediately followed it. Looking back, the first decade of the new millennium now feels like a halcyon era in which theatre was reaping the benefits of the advent of the National Lottery, combined with improved funding from central government and a healthy wider economy, before the slowdown in support from both local and central government began to have any serious negative impact.

As we enter a new era of Labour government and, as I enter my third decade at The Stage, it seemed an appropriate time to take stock of the state of play of theatre across the nation.

How best to do this?

I decided to spend November visiting theatres and arts centres around the four nations, from the most southerly in Truro to the most northerly in Shetland, speaking to someone from each theatre and seeing a show at every venue. To select which venues I visited, I limited myself to those that were hosting performances (harder than I expected) and focused on those where I had not previously watched a show, starting in Belfast on November 1 and finishing in London, at the only West End theatre I’d never visited before, on November 28.

In the end, I managed to visit 22 theatres and watch 20 full shows plus a scratch performance. I travelled by plane, train and automobile and was nearly snowed in on the Shetland Islands.

Along the way, I enjoyed theatre while sat in large Victorian receiving houses designed by our greatest theatre architect Frank Matcham, modern arts centres and small fringe theatres that occupied spaces above old working men’s clubs. The productions ranged from a one-person show about a drag artist’s childhood relationship with their father (in which I was pulled up on stage for some audience participation) to a multimillion-pound Christmas extravaganza in a converted barn in rural Norfolk. I saw plays by Shakespeare, Lorraine Hansberry and premieres from new writers.

Nearly all of it was excellent. And, put together, it created a patchwork of a sector that, despite all the challenges being thrown at it – and there are many – is still producing work of a remarkable standard and variety, while playing to good and receptive audiences at very fair prices.

Belfast

I start in Belfast on November 1. Northern Ireland has the lowest per capita arts spending of any UK nation; funding for the whole arts sector is roughly equivalent to what the Abbey Theatre in Dublin alone receives in public funding each year, at about £10 million.

My visit coincides with the Belfast International Arts Festival and I attend three festival shows at a trio of venues. Between them, they represent the key players as the city’s principal receiving theatre, producing theatre and arts centre.

Belfast Grand Opera House is a 1,063-seat, Frank Matcham-designed venue. It opened to the public in 1896 as the New Grand Opera House and Cirque and it lays claim to having one of the most beautiful auditoriums in the country, ornately decorated with a South Asian theme featuring elephant heads, pineapples and Sanskrit inscriptions: nobody fully understands why. It reopened in 2021 following a £12.2 million restoration – and looks a million dollars.

Despite the gleaming interior, the theatre’s chief executive, Ian Wilson, sums up the wider mood in Northern Ireland: “There is a great deal of frustration. We all say: ‘If we had funding like the other parts of the UK or indeed our colleagues in the Republic, what could we actually achieve?’”

Belfast has been transformed over the past two decades, but he thinks the theatre sector has been left behind. “The number of hotels is phenomenal: there are 10 hotels within 15 minutes’ walk of the theatre that we never had before. The number of tourists is fantastic. The number of cruise ships coming through is amazing. When I was a child, the shipyard was just derelict. All of those sectors are growing, and to service those sectors, you need a very vibrant, growing art sector.”

Instead, arts funding has been going backwards.

Unlike many receiving houses, the GOH still receives some Arts Council funding, but it has gone from a high of around £675,000 per year over a decade ago to little more than £200,000 today.

Due to the economics of getting shows to Belfast, the venue needs to play to 80% capacity to break even. Thanks to a mixed programme of work that features musicals, plays and extensive local amateur work, as well as comedy, opera and dance, it is currently faring well, averaging 83%.

But Wilson still has concerns about certain elements of the programme: it has been harder to find commercial plays post-pandemic, and getting ballet and opera to Belfast has proved almost impossible since the 2020 demise of a cross-border touring fund that had historically helped bring over companies including Scottish Opera, Scottish Ballet, English National Ballet and Welsh National Opera.

Since its removal, the GOH has focused on its relationship with Northern Ireland Opera, but this still means a reduced output of only four opera performances over the past year.

“When I talk to my colleagues and the rest of the UK, they can have one, two or three pencils on a week. I don’t have that luxury. And when something falls through it does punish us more than elsewhere, because we can’t replace the product that quickly. I have to work with the producers, because there’s no point bringing a show from Plymouth to Belfast and travelling all that way. So there’s a bit of jigsaw puzzle that others don’t necessarily have.”

Named The Stage’s Theatre of the Year in 2023, the Lyric is the only full-time producing theatre in Northern Ireland. It has a permanent staff of 37 and is located slightly outside the centre of Belfast in a building that opened in 2011, with a main space seating nearly 400 and a studio of around 120 seats.

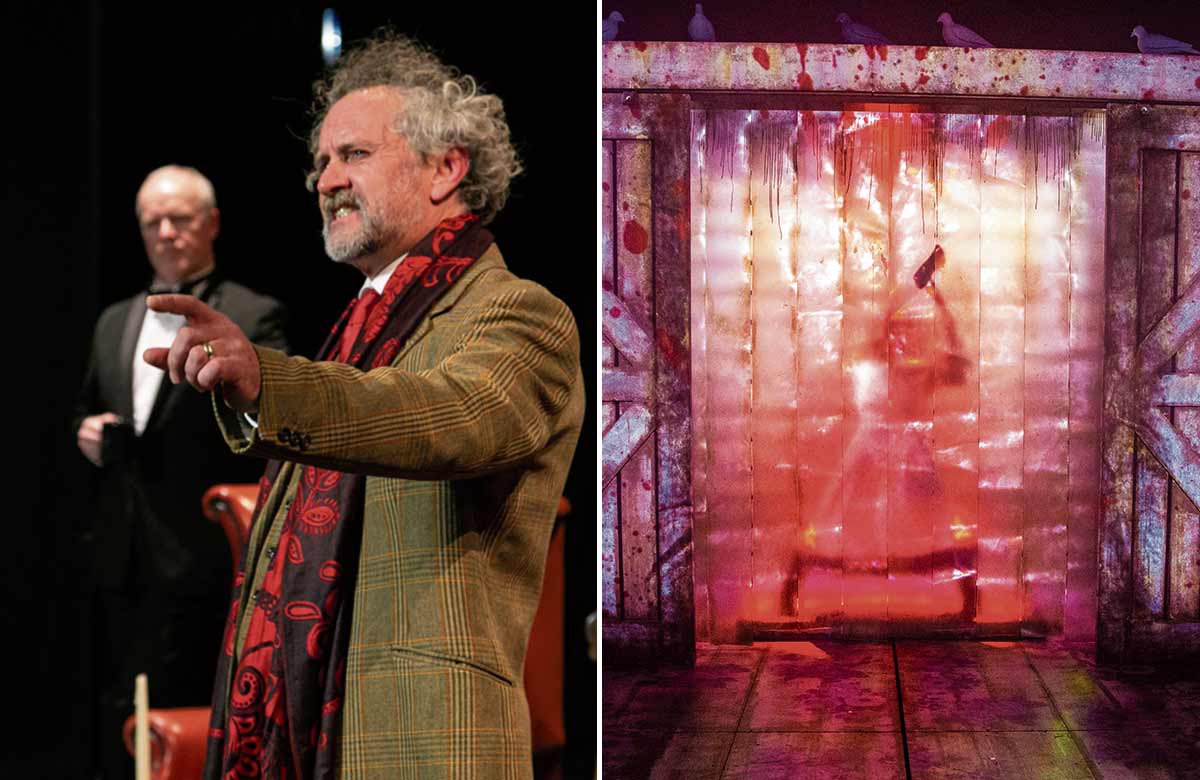

It is a prolific producer of quality work. Since reopening after the pandemic in 2021, it has produced 28 shows, of which 18 have been new writing. Highlights of the past year have included the world premiere of Owen McCafferty’s Agreement – about the Good Friday Agreement – and the production I saw, a radical reimagining of Shakespeare’s Richard III, featuring Michael Patrick, who has motor neurone disease, in the title role.

The theatre’s executive producer, Jimmy Fay, reckons that – outside film – the Lyric is the biggest employer of freelance artists in Northern Ireland.

“The Lyric is a production company that has a theatre,” he says. “It’s not a theatre that is relying on other people to bring in work. We choose what to do. We create it. We have a workshop. We commission the shows, we rehearse in the main house. We build our sets just off site there. It’s like a movie factory.”

By Northern Irish standards, the Lyric receives substantial funding – its most recent settlement was £1.4 million, which puts it on a similar footing to, say, Nottingham Playhouse in England – but that funding has fluctuated quite considerably over the past few years and has gone as low as £900,000 in recent memory, which would put it more in line with somewhere like Farnham Maltings. Certainly, it is considerably lower than the principal producing theatres in any of the other UK nations.

The big problem, however, is the uncertainty of year-by-year funding agreements: “There’s no guarantee that next year we’re going to get the same as last year, which is a bit crazy to run the business on, because you want that bedrock of funding. If you were to take away that funding, the whole place would collapse.”

He has sympathy for the Arts Council of Northern Ireland, which he thinks is “fundamentally trying to do the right thing with the resources that it has”.

“But something isn’t working. Something has to change, because actually, it’s too low. And it’s just too detrimental, particularly to freelancers. And for us, a couple of bad swings at the box office would take the grin off my face really fast.”

Fay sees part of the Lyric’s role as being a “launch pad” for other Northern Irish companies. As well as its own in-house productions, the Lyric serves as a home for outside work, especially in its second, smaller space, which hosts work from lots of independent Northern Irish companies. While I’m there, Tinderbox Theatre Company’s revival of Yerma is playing.

“I believe you need a really vibrant independent sector,” he says.

“When you have a lack of money, conservatism starts to come in, and then it just trickles down. It’s a bit like a frog in the pot of water, it’s boiling before you know where you’re at”

But it is in that independent sector where Northern Irish theatre is facing its greatest challenges. Belfast MAC, which features 350-seat and 120-seat theatres as well as art galleries, was created to be a regular home to Northern Ireland’s independent theatre sector when it opened in 2011. However, since reopening post-pandemic, it has faced crisis.

In 2023, the Arts Council of Northern Ireland threatened to remove funding from the venue. In the end, funding was restored, but the period of upheaval saw redundancies and the departure of the entirety of the centre’s senior leadership team: its chief executive, commercial director, director of finance and creative director in quick succession.

Jules Stewart is the recently appointed creative programmes manager, who heads up the theatre programming at the venue. “It was a really, really tough year, but we’re through it and we’re still here, and we still believe in the MAC,” she says.

She looks back on the years directly before the pandemic fondly, when the theatre would have produced at least two shows a year in its main space, as well as a programme of new work, “which would have been paid for by the more popular stuff… but there was so much variety. And then Covid happened”.

Unlike the GOH and the Lyric, the MAC has struggled to reconnect with its audience post-pandemic and Stewart says she has also struggled to find product that the arts centre can afford to programme, resulting in far more commercial hires and one-nighters.

One exception to that is Aurora, which is playing as part of the Belfast International Arts Festival when I visit. It is produced by Prime Cut Productions, one of Northern Ireland’s busiest and most successful independent producers. This year alone it has produced Lie Low, which played at the Royal Court in London, and The Pillowman in a co-production with the Lyric.

Una Nic Eoin is the company’s executive producer and speaks eloquently about the sector’s problems.

“There is a message coming down from our government that the culture of this place is second rate,” she says. “There’s such a lack of priority given to it. I think its placement in the Department for Communities was a terrible mistake, because you can never, ever compare an art gallery or putting on a theatre show to social housing. You just can’t. And so if you actually look at the department’s listings online, we’re always listed at the bottom.

“But when you have a lack of money, conservatism starts to come in, and then it just trickles down. It’s a bit like a frog in the pot of water, it’s boiling before you know where you’re at.”

Back at the Lyric, Jimmy Fay uses a similarly powerful metaphor to sum up the state of theatre in Northern Ireland: “I think it’s on a life-support machine. The funding is awful, but the talent is huge.”

Greater Manchester

The situation in Manchester is rather different. It’s a city on the up, with the arts at the centre of things: some areas feel like building sites, but there is a huge expansion of the city going on, with culture being proactively used for placemaking. Dave Moutrey, a key figure in the Manchester culture sector for the past four decades who now has an overarching role as director of culture and creative industries for Manchester City Council, observes that one of the key changes over that period has been that Greater Manchester has become somewhere you can actually have a career working in theatre without leaving the region. This is underlined to me during my time there by the number of creatives who have either relocated to the city – often from London – or have returned home to pursue work.

The three venues I visit have all been part of the expansion of the placemaking agenda in Greater Manchester.

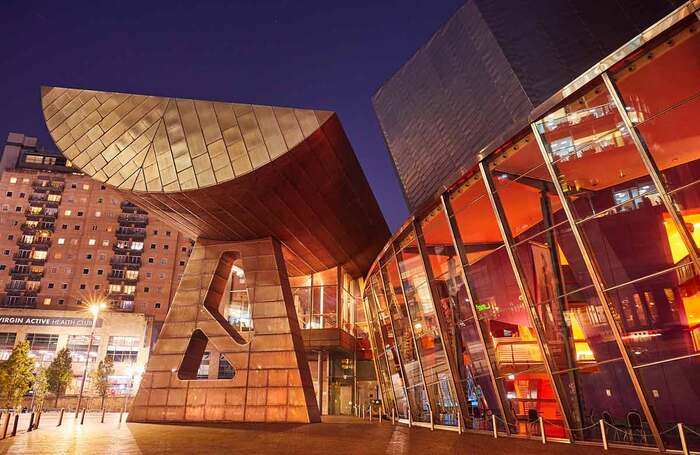

The first is the Lowry in Salford, a three-venue arts centre located in an area now known as Media City. But the Lowry’s arrival predated that of its neighbour, the BBC. It opened in 2000 and Julia Fawcett has been its chief executive since 2002. “We were doing placemaking before it was a thing,” she laughs. “Where Media City is now was our staff car park, just on rough wasteland.

“The aspiration was always that this would be a beacon for the regeneration of a city. We’re still on that journey as a city. There’s still more to do, but it’s really important that the genesis of our organisation is about that: we’re here to make a difference to the communities that we exist within and to make a difference within the city.”

Today, the Lowry is one of the UK’s leading receiving houses, but it is also more than that. Because of its three performance spaces (the Lyric, with 1,730 seats, the Quays Theatre with 440 and the Studio with up to 150) its programming is extremely varied. In addition to the large-scale touring product that you’d expect to see in a number one touring venue – work of an international standard – it is also home to community groups and local artists and, through its studio space, has helped to develop shows such as Operation Mincemeat, now playing in the West End and on Broadway.

“Many large-scale companies who regularly tour here are now coming less. So that means shorter weeks, split weeks or, if they came twice a year, perhaps they are now coming once”

One of its challenges is “the lack of great, fantastic quality touring product”, especially at the largest scale for its biggest space.

“This is the art of unintended consequences,” Fawcett says, pointing to the recent push to “rebalance” arts funding outside London. The reduced funding for London-based companies has resulted, she says, in some of them touring less. “There was never enough funding being saved from those London organisations to truly support what the regions needed anyway. So it was always a sleight of hand, but the level of cuts that were imposed on those London organisations were real enough for it then to become more of a challenge for them to tour.

“There are now many, many large-scale companies who regularly tour here, who are now coming less. So that means shorter weeks, split weeks or, if they came twice a year, perhaps they are now coming once.”

This has a knock-on effect on the Lowry’s ability to work with grassroots organisations or programme less commercial work: “A week’s programme of a production from the National Theatre brings in audiences. It financially then supports a week of contemporary dance. That won’t generate a sold-out house but is really important. That week’s run from the National will also generate enough funds to support some of our artist development work in our studio spaces.

“So the unintended consequence [of the rebalancing of funding] is that the very thing it was meant to achieve, ironically, at least in one substantial way, has had entirely the opposite effect.”

Within Greater Manchester and its growth as a creative hub, the key – Fawcett says – has been collaboration.

“No matter how healthy it is in Manchester at the moment, we are still facing the same challenges. We’re all struggling for programme, we’re all struggling for investment to support bringing more programme forward. It’s the same issues, but I think probably there’s more trust and collaboration across our region now than there has been historically or in other locations. And I think that allows us to be more collaborative.”

She points in particular to how Greater Manchester has responded to the proposal for English National Opera to relocate some of its operations to the region. Instead of a single home, ENO will work in partnership with the Lowry and Factory International to present its work.

If the Lowry was Greater Manchester’s original placemaker, its most recent is Factory International’s Aviva Studios. This £242 million building opened on the site of the former Granada television studios in late 2023. The venue has a flexible 1,600-seat theatre and an open industrial warehouse-like performance space with a capacity of 5,000. It is the poster child for former chancellor George Osborne’s Northern Powerhouse strategy.

Factory International has grown out of the biennial Manchester International Festival, which had its first iteration in 2007 and is widely credited by people I speak to with having raised the bar when it comes to the city’s cultural offering.

Aviva Studios gives Factory International its first year-round home and it is an extraordinary one, especially in terms of its scale and flexibility. But that flexibility presents a kind of blank slate for the organisation, which seems still to be at the stage where it is working out precisely what the building means.

“The transition from a biennial festival of 18 days to a year-round organisation has been a significant moment for us,” says Low Kee Hong, Factory International’s creative director. “I think in some sense we’re learning as an organisation, and the building is still teaching us many things as we’re kind of discovering it.”

In terms of its current slate of work, Aviva Studios opened with a large-scale, Matrix-inspired dance show directed by Danny Boyle, it is currently hosting the David Hockney digital art exhibition that was at the Lightroom in King’s Cross and it will soon host Hamlet Hail to the Thief, which merges Shakespeare with a Radiohead album and will see one of Aviva’s warehouse spaces converted into a theatre that resembles the Stratford-upon-Avon home of the Royal Shakespeare Company, with which the play is a co-production. Meanwhile, there is an extensive digital programme, gigs and commercial hires: when I visit, the space is preparing to host the MTV Europe Music Awards.

“The building was designed to be able to allow artists to stretch their imagination,” says Low.

Around the UK in 20 shows (part one)

1

The Vanishing Elephant

Grand Opera House, Belfast

Family show produced by Cahoots featuring impressive puppets. It tells the story of an Indian elephant that joined a US circus and performed with Harry Houdini.

2

Aurora

MAC, Belfast

New play by Dominic Montague about environmental protest and how greed is damaging the natural world, produced by Prime Cut Productions.

3

The Tragedy of Richard III

Lyric Theatre, Belfast

Adaptation of Shakespeare’s tragedy in which Richard is played as someone who had developed a terminal illness, performed by Michael Patrick, who has motor neurone disease.

4

The Haunting of Blaine Mano

Lowry, Quays Theatre, Salford

Self-produced commercial tour by a local Salford writer who has created a series of haunted-house stories set in the 1950s.

5

LIZZIE the Musical

Hope Mill revives its own production of this all-female rock musical about the alleged axe-murderer Lizzie Borden.

At the other end of the spectrum in terms of scale, if not ambition, is the Hope Mill Theatre. It’s a 145-seat venue in the Ancoats area of Manchester in a converted textile mill. It was set up by Joseph Houston and William Whelton in 2015. I visit nine years to the day that they hosted their first show.

“When we got here, people were like: ‘You’re in the middle of nowhere,’” remembers Whelton. But the Hope Mill has played a part in the regeneration of the area.

“It was no man’s land when we opened,” adds Houston. “You could see where the city ended, and then nothing happened until the Etihad Stadium, really. Now, with the Co-op Live arena that’s just been built here, the council wants to bridge that gap between the city up to this area, Holt Town.”

Hope Mill became a charity just before Covid struck and it struggled as it emerged from the pandemic lockdowns – to such an extent that it was threatened with closure and had to change its business model to produce more larger-scale work away from its home base in order to cross-subsidise its programme.

“As a small producing house, we’ve always been on that knife-edge. It was always a challenging model, certainly from a producing point of view. But then, coming out of Covid, it was almost impossible. It just didn’t work anymore,” says Houston. This, I will discover, is a common theme for venues working at the smallest scale.

One of the first fruits of Hope Mill’s new business model is currently taking place at the Lowry’s Quays Theatre, a Hope Mill production of A Christmas Carol.

This underlines the interconnectedness of the city’s arts organisation’s that the Lowry’s Fawcett mentioned. As does the fact that the show I saw in the Quays – The Haunting of Blaine Manor – actually started its life at Hope Mill in 2016.

Received work such as this has always been part of Hope Mill’s model, and it is one of the areas where the challenges have become particularly acute.

“Those independent companies that were coming here when we first opened, I’d say at least 50% of our received programme would have been Arts Council-funded,” says Whelton. “Most of them were paying hires because it worked in their favour, and they were bringing great work where they were able to pay everyone and subsidise that through their Arts Council funding. That has just got more and more challenging, and because Manchester is seen as a sort of great theatrical ecology, it is not really getting funded at all anymore, sadly, because it’s not seen as a priority.”

Houston and Whelton’s hope for the future is that they might be able to move to a larger venue in the same area of Manchester, as the regeneration continues.

“We would like to be in a bigger building one day,” says Houston. “I think that’s where we feel we’re heading. It feels like the next natural step in the journey. We are very much having conversations with Manchester City Council about our place in this area of the city. There’s a framework out at the moment for public consultation, for redevelopment, and in that framework, there is a cultural venue that’s been earmarked.”

Nottingham

I stop in Nottingham to watch a matinee performance of A Raisin in the Sun at Nottingham Playhouse, a 750-seat 1963 venue that is one of the UK’s leading producing theatres and has been enjoying something of a golden period. Alongside artistic director Adam Penford, it is led by chief executive Stephanie Sirr, who has been at the venue since 2001. She is also joint president of trade body UK Theatre, so is well placed to give an overview of the changing landscape of the country’s theatre sector.

How have things changed?

“It’s unrecognisably different. The job has reinvented itself every four to five years.

“I think people are more inclined to go to the theatre now, but people go less often. So in the old days, you’d have talked about your core audience, and it’s not that there isn’t one, but it’s a small fraction now.

“In the old days, I’d come to press night and I’d know not just the guests, I’d know a lot of the audience. It’s become probably more democratic, but it’s also harder, because your reach is much wider now, and your relationship with people is more casual. Their investment in you is literally ‘that’s a good night out’ or ‘that’s not a good night out’.”

Funding has also changed dramatically.

“If things had kept up with inflation, we would have at least, say, £3.5 million to play with, instead of the funding we have, which is £1.3 million.”

Despite this – or perhaps because of it – Nottingham is now programming more than ever. “We really sweat the asset, and sometimes I think we probably drive it a bit hard,” says Sirr.

In-house, it is producing nine or 10 shows a year, some of them co-productions, at a variety of scales. Current examples include Dear Evan Hansen, which has just gone out on a commercial UK tour, and Punch by James Graham, which will transfer to London’s Young Vic in March.

Audiences are strong, but the principal challenge facing Nottingham – alongside stagnant funding – is rising costs, like at many other theatres I visit.

“It’s the gap between what it costs to make work now versus what it cost to make work before. So, if we had the audiences of now paying what the ticket price would be, it would be fine. But costs have outstripped income.

“It’s the cost of materials – wood and steel, their price has never come back down again [since Covid]. We have been less affected by utilities than many theatres because we did a lot of environmental work in 2013, but other theatres didn’t. And, actually, these 1960s buildings are not as terribly inefficient as some of the 1980s buildings. So utilities have gone up, but that hasn’t knackered us. But the increase in the cost of wages, which is quite right, has been massive, as has the recent increase in national insurance. The cost of the recent Budget to us is in the region of £100,000.”

This is in line with the figures I am quoted by all the theatres of scale I visit: they are all facing six-figure increases in costs due to the impact of October’s Budget. One venue even reckons the changes may cost it as much as £1 million extra annually.

Sirr also identifies one of the patterns that rings true at the other theatres I visit: the larger you are, the more you are likely to be able to cope with the increased costs.

“I think if you don’t have enough seats, you have a real problem,” says Sirr. “I don’t think that’s properly respected. We’ve got 750, which is just about enough. It means when we do sell out something, we’ve got enough there to build a nice little rump to pay for the other things that are not going to sell out and were never intended to. If you’ve got 500 seats, it’s not really enough, but you’ve got the same demands made of you, and you’re subject to the same costs, you’re paying the same wages. I think that’s a problem that’s not addressed sufficiently.”

Newcastle

En route to Scotland, I stop in Newcastle. Like Manchester, it has a genuine theatrical ecosystem. In addition to the principal unfunded receiving theatre, the Newcastle Theatre Royal, there are two funded producing theatres – Live Theatre and Northern Stage – and high-quality fringe venues such as Alphabetti (another former winner at The Stage Awards) and, not far away on the Northumberland coast, Laurels in Whitley Bay. There is a group called Newcastle Gateshead Cultural Venues that links many of the city’s arts organisations together.

Despite it being Monday night, the 1,247-seat Theatre Royal – a grade I-listed venue that originally opened in 1837 – was full for a touring production of Hairspray.

Speaking after its run has ended, Marianne Locatori, the theatre’s chief executive since 2021, explains the show beat its box-office targets and, more generally, the venue is back up to pre-pandemic audience levels, playing to 71% capacity last year.

Her concerns relate less to the current situation for the Theatre Royal – although costs and margins are a challenge, as is selling large-scale drama – and more to the bigger picture.

“I think the challenge for us is the interconnectivity of the ecology in the sector,” she says. “We’re so interdependent, and the worry is if one area is really challenging, for example mid-scale touring, that does affect the large scale.

“If that doesn’t work, what we have is a pipeline issue. We have a talent issue. So I’m conscious that while we’re doing okay, it doesn’t work unless it’s all working.”

She is also concerned that while there is good large-scale touring product available at the moment, there is not enough in the pipeline.

“As a sector, we have to start looking at where’s the new, fresh work at the large scale. I don’t think it’s a problem yet, but I think we need to be cognisant of that. So I think the Arts Council’s new touring fund is really good. We really have to make a success of that as a sector.”

One of the ways that the Theatre Royal is looking to address this challenge is by serving as a co-producer on certain projects. It is a co-producer on the David Pugh-led touring production of Pride and Prejudice* (*Sort Of) and was a co-producer on a new play called Gerry & Sewell, based on Jonathan Tulloch’s novel The Season Ticket, which became cult Geordie film Purely Belter.

The project’s genesis is a great example of both the culture of collaboration in Newcastle and that interconnectivity between the small-scale indie sector and a large regional venue such as the Theatre Royal. The show started life at the 70-seat Laurels theatre (named after Stan Laurel) in Whitley Bay, before having a production at Live Theatre and then a full week-long run on a large-scale at the Theatre Royal earlier this year.

Gerry & Sewell was created by Jamie Eastlake, who runs Laurels from the backroom of an old working men’s club. He had previously run the Theatre N16 fringe venues in London before moving back home to the North East when that company ran into difficulties after a financially unsuccessful Edinburgh Fringe and the sudden death of his business partner. He very nearly quit the industry.

“I was in £36,000 worth of debt,” he recalls. “The whole model of N16 was that there was no cost to any company. It was trying to give people a chance. And everything we’d done, we were now literally doing the opposite. It was just horrific.”

Living in his mum’s spare room, he had all but given up hope when Flesh and Bone [an N16 production that played at the Soho Theatre] was nominated for an Olivier award.

He took on multiple jobs – working at a golf club, selling boilers – and paid off the debt in a year. He’d just got to the stage where he was about to open what he describes as a “tapas arts bar” called Laurences (after Laurence Olivier) in nearby Blyth when Covid hit. He was still operating as Theatre N16, which he hadn’t shut down, and this enabled him to access the government’s Cultural Recovery Fund. But, before Laurences was able to stage any shows, the second lockdown shut it down and he was forced to turn the venue into a full-time takeaway. It was, he says, “soul-destroying”.

Eastlake eventually discovered the site that would become Laurels and opened in 2021. Initially, Laurences and Laurels were run in tandem by Eastlake and comedy writer Steve Robertson, before the pair decided to focus on Laurels alone from 2022. It has moved into becoming an independent charity over the past year. Funding has been hard to come by, with Eastlake saying that he has had 19 rejections in a row from the Arts Council.

It’s clear that Laurels is operating on a knife-edge, but it has managed to programme 60 theatre shows over a three-year period, including 11 in-house productions, the most successful of which has been Gerry & Sewell.

“That’s kept us alive,” he says. “We were on the verge without that.” Like Hope Mill in Manchester, for Laurels to survive, it needs its shows to have future lives beyond its walls.

Around the UK in 20 shows (part two)

6

A Raisin in the Sun

Nottingham Playhouse

Top-class revival of Lorraine Hansberry classic, directed by Tinuke Craig, that is a co-production between Headlong, Nottingham Playhouse, the Lyric Hammersmith Theatre and Leeds Playhouse.

7

Hairspray

Theatre Royal, Newcastle

Mark Goucher, Matthew Gale and Laurence Myers’ high-class touring production of Marc Shaiman and Scott Wittman’s musical about the 1960s civil rights movement in Baltimore.

8

Fixing

Alphabetti, Newcastle

Solo show from Matt Miller that combines drag and car mechanics to tell the dual narrative of young boy Matt and his adult drag alter-ego Natalie Spanner.

9

Miracle on Deanston Drive

(A Play, a Pie and a Pint), Òran Mór, Glasgow

World premiere of a Glasgow-set solo show by Katharine Williams, in which a cabbie saves the day when a baby falls ill.

10

101 Dalmatians

King’s Theatre, Glasgow

Runaway Entertainment’s touring version of Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre’s staging of Douglas Hodge’s musical adaptation of Dodie Smith’s novel, starring Faye Tozer as Cruella de Vil.

The similarly tiny Alphabetti (80 seats) in Newcastle’s city centre and the theatremakers who run it have also faced severe challenges staying afloat.

When it won The Stage’s Fringe Theatre of the Year Award in 2023, then artistic director Ali Pritchard revealed he had not been able to pay himself for the previous two months.

He has since moved on from the fringe theatre and been succeeded by Edward Cole, one of the co-founders of Hull-based theatre company Middle Child.

Like Eastlake, Cole left the theatre industry for a period. “I was really tired of working with companies that were just focused on still being alive in a year’s time. It was just an exhausting way to live your life.

“When Covid happened, I moved up north and moved out of the sector, and I was working full-time in hospitality for two or three years, doing events management, and then a year ago, I left that because it was soulless. It’s not who I was,” he recalls.

It was the Alphabetti job that encouraged him to return.

“There’s a reason I do this, and there’s a reason that I’m passionate about it. And I remember saying when I interviewed here: ‘Look, in order for me, as a freelancer, to have a career in Newcastle, I need there to be a flourishing and dynamic and working Alphabetti Theatre.’ I think it’s such an important place.

He is early on in the job, with Pritchard only finishing his handover to Cole last month, just before we meet, and he’s still exploring what Alphabetti will look like.

“It seems like there’s never been such disparity between the high-level work and the big-scale stuff and the much smaller scale. And that is having an effect on career paths,” he says.

“A lot of freelancers have found that some of the routes towards regular work have dried up. And it seems really natural that that’s where the fringe theatres can step up to the plate and say this is part of our responsibility.

“But it’s hard, because how do we prioritise our responsibility to others and to the freelance sector when we’re having a hard enough time just making sure that we’re staying afloat?

“There’s a chance for us to stand up now and say that we’re really bloody important. Not enough people are getting access to culture, not enough artists are getting work opportunities, not enough theatres are taking risks and trying new work out.

“Where is the new, exciting, radical work coming from? Where are the development opportunities for artists? They’re here in fringe theatre and, if you invest in that, that is going to impact every single other strand of the theatre ecology across the country, because we’re going to create new ideas, we’re going to create new plays, we’re going to supercharge the creative pipeline into the industry.”

Glasgow and Aberdeen

Glasgow’s lunchtime theatre company, A Play, a Pie and a Pint is an example of this pipeline in action. It produces 30 plays, all world premieres, every year. They are under an hour in length and tickets cost less than £20, which includes (as the name suggests) a pie and a pint. The company is based at Òran Mór in Glasgow’s West End. It does not own the building, nor entirely programme it, producing just the lunchtime slot at the venue. Its shows are also often presented as co-productions with other theatres across Scotland and will go on to play at those venues and at the Edinburgh Fringe. The day after I visit Glasgow to watch A Play, a Pie and a Pint at Òran Mór, I see one of its other productions at the Lemon Tree in Aberdeen.

“No shade on any other theatre, but because of the funding situation and other things over the past five to 10 years, a lot of the places that were expected to be Scotland’s new-writing institutions have been doing a lot less. I think we do a lot of heavy lifting,” says recently appointed artistic director Brian Logan. “We employ more freelancers than any other theatre in Scotland and we variously say that we produce more new plays a year than any other theatre in Scotland, the UK… Europe. We’re waiting for someone to contradict us.

“It felt like a sort of abusive relationship between the government, Creative Scotland and the sector, whereby promises and announcements would be made and then withdrawn”

“But there’s an important asterisk to put next to that. No one is suggesting that the PPP way of making theatre should become the default. We pay well, but we’d love to pay writers more. Two weeks’ rehearsal is great, you can achieve brilliant things, but sometimes you can [only] achieve perfectly all right things. But we fully acknowledge that theatre in Scotland should be better supported and our model shouldn’t be the only model. But, equally, we are proud, glad, relieved to be in a position where we can still create a lot of work and give audiences a lot of great stuff.”

The company receives regular funding from Creative Scotland. It has applied for an uplift in funding and is waiting to hear back. Indeed, the funding situation is a lively source of conversation during my time in Scotland, which predated the recent £34 million boost to culture spending announced in the Scottish government’s draft Budget.

But the months leading up to that announcement have been fraught.

“It felt like a sort of abusive relationship between the government, Creative Scotland and the sector, whereby promises and announcements would be made and then withdrawn,” says Logan.

The lack of uncertainty has been damaging. “Even now, we’re at a point where I’m programming a spring season, not knowing how much money we’ve got, and having a bunch of co-presenting partners on whose financial contributions we depend, all saying they can’t commit to all the activity before the end of March.”

Logan acknowledges that the impact this has had on his company has been less severe than on some other parts of Scotland’s funded sector. It will be interesting to see – now that extra funding has been earmarked – how this translates into the specific settlements for individual companies, which are expected in January.

While in Glasgow, I visit the King’s Theatre – another Frank Matcham-designed, Victorian venue. It is one of two (along with the Theatre Royal) operated in the city by ATG Entertainment, the UK’s largest commercial theatre operator.

I take the opportunity to speak to Julia Potts, who is business director at ATG and responsible for overseeing operations at its number one touring venues, including the two Glasgow theatres. The King’s operates as a traditional receiving house, while the Theatre Royal is home to Scottish Opera and ATG Entertainment programmes in the weeks it and Scottish Ballet are not using the venue.

“In terms of product and content, things have really only got better. We feel incredibly fortunate with the quality of content that is available to us, and that is absolutely key to why occupancy is strong”

The King’s is undergoing some work on its facade and Potts acknowledges that the interior “does require further investment”, which ATG is in “active conversation” about with the local council.

“The overall health of our theatres in Scotland [ATG Entertainment also operates the Edinburgh Playhouse] is broadly similar to all the number one venues we operate and it’s pretty good. The key thing is that we are seeing overall average occupancy in the regions grow year-on-year, which is fundamentally a really pleasing position. And that is true in Scotland as well.

“But fundamentally, what is interesting about my job making these theatres successful is that you can’t do exactly the same thing everywhere, and that’s really important. So even when shows are touring, there are always nuances to what plays where and when and for how long.”

Generally, though, business is strong. “In terms of product and content, things have really only got better. I think we feel incredibly fortunate with the quality of content that is available to us in our theatres, and that is absolutely key to why occupancy is strong,” she says.

“Post-pandemic, we were all really concerned as to whether our audiences would come back, and the truth is that they have, for the most part, and we have also acquired a new audience and a more diverse audience as well. I think we don’t fully understand why, but it is a good thing, and it is something to be celebrated. Now that audience needs to be nurtured, and it’s about getting them to come back.”

Costs are an increasing challenge, but she adds: “Things do feel pretty positive from our perspective.” Like some other interviewees, Potts highlights “a reduction in the amount of quality drama that is available on the touring circuit” and, rather like Locatori in Newcastle, her concerns relate to other parts of the theatre ecosystem. “We learned in the pandemic, didn’t we, that the health of our sector depends on everybody’s good health, so I do have concerns about that,” she adds.

“I worry about the future viability of venues that are smaller, more reliant on funding, less able to programme the content that, in our world, sees very buoyant responses from audiences. You know, the big musicals, people absolutely want to come and see them, and that’s very helpful to us. But not everybody can present that work, and nor should they.”

About 150 miles away, the charity Aberdeen Performing Arts operates three of the city’s principal venues on behalf of the city council: His Majesty’s Theatre (1,400 seats), the Music Hall (1,300 seats) and the Lemon Tree (550 seats and a 166-seat studio). As well as these, there is a privately operated 530-seat theatre, the Tivoli.

“We have the luxury of three different venues of varying scale and also varying purpose,” explains Aberdeen Performing Arts chief executive Sharon Burgess. “What it gives us is this portfolio of spaces that allows us to be perhaps more innovative and perhaps more entrepreneurial than a traditional theatre can be.”

As previously mentioned, I visit the Lemon Tree for a lunchtime small-scale production from A Play, a Pie and a Pint. In the evening, I watch Pitlochry Festival Theatre’s production of A Streetcar Named Desire at His Majesty’s. This is one of the rare examples of large-scale touring classic drama I encounter on my travels. It is also extremely good.

Burgess admits that it is a bit of an outlier for her programming as well, but she’d like to see more of this type of work.

“Scottish work of scale is more difficult. It would be nice if we had a better kind of pathway for those pieces of scale. I mean, I can take Chicago from the West End and know that I’m going to get a financial return and I’m going to fill that theatre, but I want to just as much take new work from Scottish producers.”

She is able to cross-subsidise this kind of work with the brand-name musicals the theatre more regularly hosts. She gives Dundee Rep’s Sunset Song as another example.

“That was never going to be commercially, you know, a big hitter, but it was a really important piece for us. It was important for our identity. So, we happily got behind that.”

Burgess is one of the more optimistic people I speak to in Scotland when it comes to the funding situation. She has, in the end, seemingly been proved right.

“My instinct is the Scottish government is going to come good,” she told me before the budget announcement. “I do think that the money is going to come. I do think the promise is going to be upheld.

“I think we’re in a moment of real change. And I do think people have to be optimistic, because doing nothing is not an option. Getting things done on the smell of an oily rag is not good enough these days, because we want to be great employers, with people who have satisfying careers in our industry, but that needs investment.”

Shetland and Truro

Two of my next stops are at opposite ends of the country, as I visit the UK’s most northerly and southerly theatre buildings.

In Shetland, there is some local debate about which venue qualifies as the UK’s most northerly theatre. Mareel is a multi-use arts centre that opened in 2012 and features a 250-seat main space, a cinema, art galleries and recording studios. The Garrison Theatre is an old drill hall that was converted into a 280-seat theatre in 1942 to entertain troops who were stationed in Shetland during the Second World War. Visiting names included George Formby and Gracie Fields. Today, it is run primarily as a community theatre and is home to Shetland’s two main community theatre companies: Islesburgh Drama Group and Open Door Drama. They alternate the annual panto at the Garrison.

There is no real question about which of the two venues is further north (it’s Mareel), but there is some dispute over whether to classify it as a theatre or an arts centre. I decide to hedge my bets and visit both it and the Garrison.

At the Garrison, I watch Islesburgh Drama Group present an excellent amateur production of Kindertransport. One of the cast, Stephenie Georgia, is also the founder and managing director of the ALICE Theatre Project, a community interest company she set up in response to the fact that “while there’s a lot of opportunities in Shetland to do drama and there’s two quite large community drama groups, what there isn’t is an academic framework for learning about drama”.

Through ALICE, she has 120 children aged five to 13 attending her classes, and runs the Shetland Youth Theatre, for children aged 12 to 19. She also teaches as part of a Skills for Work programme in drama that is accredited by the University of the Highlands and Islands and run by Mareel. Several of her students have since gone off to study drama – one at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland. “There’s a lot of people I’m working with who are now thinking it is a viable career for them, which is lovely. And I always think, even if they don’t go on a path of working in the professional theatre industry, what they learn from it is so valuable.”

Around the UK in 20 shows

(part three)

11

Blast Off, Starburst

(A Play, a Pie and a Pint), The Lemon Tree, Aberdeen

Catriona MacLeod directs her own time-bending play about grief and astrophysics, as a young woman copes with the loss of her mother.

12

A Streetcar Named Desire

His Majesty’s Theatre, Aberdeen

Pitlochry Festival Theatre’s high-class, traditional and impressively performed revival of Tennessee Williams’ classic transfers to Aberdeen.

13

Kindertransport

Garrison Theatre, Shetland

Local community company Islesburgh Drama Group staging of Diane Samuel’s 1993 play examining the effects that relocating from Germany to Manchester during the Second World War had on a young Jewish child in adulthood.

14

The Swan of Salen

Mareel, Shetland

A trio of clarsach (Scottish harp) players perform a Gaelic version of Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake, accompanied by a video recording of dancers performing a ballet, merging its story with Scottish folk tale the Swan of Salen.

15

Thursford Christmas Spectacular

Thursford Steam Museum, Norfolk

Completely sui generis big-budget Christmas show that has been running since 1977 in a converted barn in rural Norfolk.

Graeme Howell is chief executive of Shetland Arts, the organisation that operates Shetland’s three principal arts spaces: Mareel and the Garrison in Lerwick, and Bonhoga Gallery in Weisdale.

Howell joined in 2014, having worked at organisations including Colston Hall in Bristol, Norfolk and Norwich Festival and Nottingham Playhouse.

Shetland Arts’ principal funder is the Shetland Charitable Trust, which was set up in 1976 as part of a deal to ensure that the islanders benefited from oil drilling in the North Sea nearby.

It funds Shetland Arts to the tune of £800,000 annually, with the arts organisation also receiving regular funding from Creative Scotland of around £250,000. This may sound like like a lot for an arts centre that serves a population of 23,000. However, the cost of getting work to Shetland is much higher than probably anywhere else in the UK – it’s 12 hours by ferry to ship any set or equipment, and the geography of the archipelago produces its own challenges.

“We have the remit of delivering arts development across Shetland. If we’re travelling to Unst, which is our most northerly community, to put a show on at the Baltasound Hall, that’s a two-and-a-half-hour drive, two ferry trips. That’s the same as Midland Arts Centre delivering on the west coast of Wales, which is nuts. The geography of Shetland is very long and thin. We occasionally send shows down to Fair Isle, which is 25 miles south of Shetland. I lost my production manager there for five days once. All the flights were cancelled. He ended up having to send his kids to the local school for a bit.”

I get a small taste of these challenges a couple of days later when I try to leave Shetland and my intended flight to Edinburgh is cancelled due to heavy snow. That is a story for another time.

While the Garrison’s programme largely focuses on community work and one-nighters, it occasionally hosts touring professional theatre if the company needs a proscenium-arch space. Meanwhile, Mareel has a busy programme of music, performing arts, visual art and cinema, which features lots of theatre broadcasts.

“There’s maybe about 100 shows a year at Mareel, something like 30-odd at the Garrison,” says Howell.

Visiting companies have included the Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Scottish Ballet and the National Theatre of Scotland. Vanishing Point was recently in town making a show.

But bringing in companies from outside Shetland is far from easy.

“There’s quite a cost now to bring the artists here and you’ve obviously got the environmental impact that needs to be considered. There’s quite a lot of debate that the ferry may be more polluting than flying, because it’s a 12-hour ferry ride, and it’s an hour’s flight on a modern plane. So there’s all this that goes backwards and forwards, and on top of that you’ve got the impact on people’s lifestyles. If you’re committing to come by ferry, which arguably may be the more sustainable approach, you’re committing to another two days away from your family, and that may not be good for you as a person.”

And sustainability is not only an issue for artists.

“I’m really interested in whether there’s a model we can develop for a car-share scheme for audiences,” says Howell. “So if you’re driving down from North Mainland, you might be able to pick someone up in Brae.”

“There is a real sense of public ownership of Hall for Cornwall, due in part to the fact that locals saved it from being turned into a supermarket in the 1990s”

Car sharing is also a subject that comes up in Truro when I visit Hall for Cornwall, another theatre that draws its audiences from an extended catchment area. It is the most southerly theatre I visit on my trip and, arguably, the most southerly year-round theatre in the UK. Certainly, I think, it’s the most southerly year-round indoor theatre of scale in the UK. The Minack in Porthcurno is further south, but is largely dark over the winter. It also doesn’t have a roof.

Although it’s not as marked as Shetland, geographical isolation is an issue for Hall for Cornwall. Julien Boast, its chief executive since 2011, refers to Cornwall as “an exploded city”, in the sense that the county has the services of a world-class city, but spread over a larger area. This informs how he programmes its 1,350-seat theatre, which reopened in 2021 after a £26 million revamp that has helped transform the space into one of the most beautiful and welcoming in the UK.

The venue’s subsidy accounts for about 8% of its income, putting it on a similar level to the Lowry and Aberdeen Performing Arts – it has some funding, but the bulk of its income is earned.

Interestingly, the theatre’s deputy chief executive, Julie Seyler, observes that when the venue reopened and had to restaff in 2021, it benefited from the effects of the pandemic causing many theatre workers to relocate.

“We picked up quite a lot of London-based folk – especially freelancers – who had come home because they couldn’t afford to keep their rent up,” she says.

Audiences are good – and ahead of targets since reopening – while the recent refurbishment has given the venue more capacity to play with. Boast is generally optimistic for Hall for Cornwall.

“It’s as much fun as you can have with a job,” he says. “That’s not being smug at all. We’re in a very, very brilliant space to be, because it’s always been culturally driven. It’s part of the Cornish DNA. They’re quite European.”

Indeed, there is a real sense of public ownership of Hall for Cornwall, due in part to the fact that locals saved it from being turned into a supermarket in the 1990s. Its name came from that local campaign.

If Boast has concerns, they are more programme-based. There are challenges attracting original opera and ballet due to funding reductions, and he would like there to be more touring circus available. Meanwhile, he also points to the death last year of commercial producer Bill Kenwright as a large challenge for the touring market, given how many of the shows he supplied.

“I wonder if anybody understands that that man was the backbone of touring, and it’s great Jenny [Seagrove] and the team are holding that together, but his personal drive was phenomenal. I wonder if our industry just washed that away and didn’t really reflect on the enormity of what that man was.”

Thursford

Between my trips to the north and south of the country, I venture east to visit the Thursford Christmas Spectacular.

This feels, in a wonderful way, like a break from reality. The show’s home is a converted barn on an old farm in rural Norfolk. Since starting in the mid-1970s, the production has developed into a £5 million extravaganza with a 120-strong cast of singers, dancers and musicians, top-quality technical equipment and impressive costumes. In addition to the 1,400-seat theatre, there are restaurants, cafes and a year-round Christmas shop on site, as well as a Christmas light show and a Santa’s grotto. It even snows while I am there.

While I have lunch with John Cushing, the director and producer of the show and really the mastermind of the whole thing, there is a queue of audience members politely waiting to come up and tell him that they’ve been coming to see the show for the past 20 years and it’s the highlight of their year.

Every day, up to 50 coach parties from around the UK and beyond bring audiences – mostly in their 60s and 70s – to watch the Christmas Spectacular, which is like a cross between a Las Vegas revue and an end-of-pier show, but Christmas themed.

Audiences remain incredibly healthy – nearly every show is a sell-out – but if there is one concern for Cushing it is that there appears to be a reduction in coach parties.

“Since Covid, the clubs have not reformed. There used to be a club for everything – dancing, singing, writing, books, gardening, you name it. So the coach operators have lost – and we’ve lost – the clubs. But we have made it up with cars by advertising heavily, which we never used to do.” That has meant slightly increased prices.

The show also faces several other challenges that are, if not unique, then almost so, among the theatres I visit.

Due to the older demographic of Thursford’s audience, Cushing points out: “Most of these people would probably be getting heating allowances, so they’ve had that taken away, and that’s their £200-odd, which they would have used to come to Thursford. So that’s challenging.

“The other challenge that coach operators have is that they have really struggled with hotels, because the government is requisitioning all these hotels in the area [for asylum seekers]. That has affected so many tourist attractions.”

Around the UK in 20 shows (part four)

16

Murder on the Orient Express

Hall for Cornwall, Truro

Fiery Angel touring stage production of Agatha Christie classic, which is given a fresh, theatrical take by director Lucy Bailey.

17

Birdsong

Theatre Royal, Bath

Original Theatre’s stage adaptation of Sebastian Faulks’ novel about the First World War has become a staple of the number one touring circuit.

18

A Christmas Carol

Sherman Theatre, Cardiff

Delightful, energetic, musical version of Charles Dickens’ story by Gary Owen relocates the action to Cardiff and turns Ebenezer Scrooge into a woman, brilliantly played by Hannah McPake.

19

Hamilton

Wales Millennium Centre, Cardiff

Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Broadway mega-hit plays a two-month run in Cardiff as part of its UK tour, produced to his usual high standards by Cameron Mackintosh.

20

The Phantom of the Opera

His Majesty’s Theatre, London

The West End’s second-longest-running musical was revamped four years ago; the new production and cast excel, keeping Andrew Lloyd Webber’s 1986 hit feeling truly fresh.

Bath

On the other side of the country and in a completely different, less-tinselly way, Theatre Royal Bath is – rather like Thursford – its own little bubble. The venue has three performances spaces (the 900-seat main space, 120-seat Ustinov Studio and 120-seat the Egg, its venue for children and young people). It also has plans to open a fourth. This is all focused on a smallish city-centre site and is run without any core external subsidy.

Instead, the Theatre Royal has developed a model where the activities of the main house, and especially its commercial touring subsidiary Theatre Royal Bath Productions, subsidise the venue’s other activities.

Danny Moar, who has been director for 28 years, explains: “We didn’t produce before I came. I think there was a youth theatre, but there was no education department. There was no Egg, there was the Ustinov but not in the shape it is in now.

“It was a successful, pretty standard touring house. I remember when I ran Blackpool Grand, which was a hard thing to run, being quoted the figures that Bath was doing for the same shows. And it was always like: ‘Oh my God, it’s amazing.’ So it’s always been good, particularly for classic revivals.”

He admits that he stumbled on its current model almost by accident.

“The concern then, which is still the concern now, is how to get enough good product,” he explains. “The first show we ever produced was a Derby Playhouse production of The Glass Menagerie with Gwen Taylor. That show finished at Derby and I had a week gap, but irritatingly my week out didn’t happen till a bit later. So to get the show to fill that gap, I had to find two other venues that would take the show before Bath. So I just called up, I think it was Malvern and Cambridge, and said: ‘Do you have a gap?’ They did. The show cost, say, £20,000 a week to run, and I charged them £30,000. So, I made £20,000 or £30,000. I thought: ‘That’s nice. Yeah, let’s do that again.’”

This has since built up into the model the theatre has today, where it is one of the UK’s most prolific creators of touring drama – over the past two years, it has produced about 30 shows.

“Things are really good at the moment,” Moar continues. “In Bath, when we tour, and in the West End, we’re well ahead of budget, forecasting a healthy surplus for this year, even after paying for all the not-for-profit stuff. It’s not that there aren’t problems – every day there are 20 problems, but they’re not existential problems.”

One of these is the increase in employers’ national insurance contributions, which will cost Bath £250,000. “That’s irritating, but not fatal,” he adds.

He points to the success of the West End as a key driver for theatre around the UK.

“I think the success, the buoyancy of the West End, is really, really important. Even if people don’t go to see a show in the West End, the fact that there are so many big stars just makes theatre itself visible and glamorous, which we can all benefit from.”

Back in Bath, Moar’s next project is the creation of a fourth performance space.

“It’ll be for professionals at the beginning of their careers doing shows there, or it’ll be amateur productions. But the idea is that it will be nestled physically right in the centre of our theatre, and all those groups will benefit from the professional expertise and professional people working at the theatre in terms of marketing, production activities, box office, everything.”

Cardiff

The penultimate stage of my whistle-stop tour is Cardiff, where I first visit the Sherman Theatre, originally built in 1973 as part of Cardiff University.

I watch a 10.30am schools matinee production of the Sherman’s musical version of A Christmas Carol. Like much of the theatre’s work, it has a distinctively local flavour, the action of Dickens’ novel being transposed to the Welsh capital.

I am nearly the only person in the full 450-seat auditorium who is not a schoolchild or teacher. When audience interaction is asked for, the noise is like nothing I have ever heard. Otherwise, the kids are impressively attentive. It’s a magical thing.

Indeed, there must be something like magic going on at the Sherman, given the quality of the work this theatre is producing on relatively meagre resources. I am genuinely shocked when its chief executive, Julia Barry, and artistic director, Joe Murphy, tell me that the theatre has a full-time staff of only 22. In the past year, it has produced seven world premieres. Several theatremakers from Sherman productions have featured at The Stage Debut Awards.

“The year has been a tale of two halves, really,” says Murphy. “It’s been a really great year artistically, the artists we’ve had have been absolutely incredible. The voices we’ve been able to put on our stage have been amazing. More and more, we’re telling these local stories with a global resonance, and that has really connected with the audience.

“Our audiences are reaching the highest levels they’ve ever been, so that’s really exciting, but the fight to maintain that is costing so much on a human level. Our staff, the most extraordinary staff, and our artists – everybody’s having to work over-capacity to be able to deliver that.”

The state of play in Wales reminds me of the situation described to me by many of the theatremakers I met in Northern Ireland: it is a sector producing some great work, but operating on fumes.

From the Sherman, I head to Cardiff Bay to visit the Wales Millennium Centre, which celebrated its 20th anniversary the day before I arrived. It is currently playing host to the UK tour of Hamilton.

Business is good in the WMC’s 1,900-seat Donald Gordon Theatre, but the venue’s creative director, Graeme Farrow, underlines the problem of costs facing many theatres across the UK. “Essentially, WMC costs £1 million more to run than it did a few years ago,” he says. “And that’s energy costs, materials, staff, and then national insurance is going to cost us about £200,000. So, we’re pretty much 85% full in our theatre every year, right across the year. In terms of the business model, if we sold every single seat in the house and got an extra 15%, the net value of that to us is probably just over £1 million. So, to actually stand still, we’d probably have to sell every single seat.

“It’s got to a stage where if this is going to be it, and funding isn’t going to rise with the cost of living or even just under inflation or whatever, then we are actually just going to have to look at a different model.”

Notably – as with several of the other large-scale principally receiving houses I have visited – this new model involves the creation of an additional performance space. WMC already has a second 250-seat studio space, but it is now planning to create a third space that will have 550 seats and principally show digitally focused work.

This is also linked to one of the other challenges that Farrow identifies.

“The large-scale sector is healthy,” he says. “But I think there is a slight alarm bell. What’s that going to look like in five and 10 years’ time? To remain healthy, people need to create new work. And I know this sounds really trite, but it can’t just only be exploiting intellectual property that’s currently with film.

“It’s healthy that you always have curveballs that break through like Operation Mincemeat, but I think we need more of them, and with the costs associated with touring increasing, we, as a business, are worried about whether we can sustain touring product for five, 10 years into the future, at the same level.”

London

I finish my tour, on November 28, four weeks after I started, at the only West End theatre I have never visited:His Majesty’s, where Andrew Lloyd Webber’s The Phantom of the Opera has been playing since 1986.

Like Hamilton, which I saw in Cardiff, Phantom is produced by Cameron Mackintosh Ltd.

Its managing director, Alan Finch, explains that since reopening in its renewed version after the pandemic, the production is now playing to around 92-94% attendance; the closure of its Broadway sister show has given London audiences “a huge boost”.

As in London, attendances are strong on tour for CML’s shows, but rising costs – including several hundred thousand pounds a year in national insurance contributions – “make the landscape extremely challenging”, says Finch.

He also echoes the concerns of others working at the larger-scale end of the industry when he points to challenges further down the pipeline. Prior to CML, Finch’s background was in regional theatre and he fears for the impact that reduced funding is having on the talent pipeline.

“I started at 16 as an apprentice lighting technician and worked through the ranks, training on the job in Nottingham, Bolton, Plymouth and Chichester. In Nottingham during the 1980s, we created a new play each month – but now, too many regional theatres are struggling and not able to create as much work or employment opportunities as they used to within their local communities. If Nottingham Playhouse had not had a grant to tour to its local mining communities, I might not have been encouraged to apply for a job I subsequently got. The pipeline and development of writers, creatives, actors and technicians is diminished in a regional context – we must protect what we do have, ensure it thrives and maximise and nurture future talent.”

To that end, the Mackintosh Foundation (of which Finch is a trustee) supports 13 fully financed posts assigned to different regional theatres working across backstage departments such as production management, lighting, sound, costume, and wigs, hair and make-up.

And what of the show itself? If I’m honest, I was expecting Phantom to be a little dusty after nearly 40 years in the West End, but it’s nothing of the sort. Both theatre and the production were refreshed during Covid and the result is that this is now as good a theatregoing experience as you can have in London.

It also makes an appropriate bookend for my journey. The Grand Opera House in Belfast (the first theatre I visited) opened in 1896, designed by Frank Matcham, His Majesty’s opened in 1897, designed by the other pre-eminent theatre architect of the era, Charles Phipps.

Meanwhile, the two shows I saw at these venues, The Vanishing Elephant and The Phantom of the Opera, both featured large-scale representations of elephants on stage. Afterwards, I pack up my bags and return to my home… in Elephant and Castle.

What did I learn?

From impractical train timetables to geographical isolation or the scarcity of touring opera, each theatre I visited faced its own unique trials and tribulations. But what were the challenges that united them? And what can the sector – and the government – do to help address them?

What threads can be drawn together from all this? What themes?

In a nutshell, the bigger and more commercial a theatre operation is, the healthier it seemed to be. Large receiving venues that are not granted any subsidy tended to be in the most secure position.

I think this is because of another generality that seemed to apply pretty consistently across the waterfront: audiences are strong, the quality of productions available is good, the main problems that theatres are facing relate to costs. These costs vary from venue to venue, but some – such as the impact of the recent hike to employers’ national insurance contributions – are pretty universal.

The theatres that are best placed to respond to these increased costs are the ones that rely most on earned income and therefore have control over the greatest proportion of their revenue. For smaller-capacity theatres, or ones that rely more on public funding, this is much harder.

When it comes to funding, there is widespread frustration – and not only with the reduced level of subsidy.

Interestingly, a number of people called for large shake-ups in the way the arts are funded.

To pick two examples: Stephanie Sirr at Nottingham Playhouse thought that funding should be divided between theatre production and social outputs, so that the latter was funded by parts of government other than the Department for Culture, Media and Sport. Meanwhile, Graeme Howell in Shetland had a different suggestion: “There should be a process about facilities and there should be a process about content, and you could apply for both. However, you cannot assess what Shetland Arts does and what a touring dance company does in the same way. It can’t be done.”

Risk was also a regular topic of conversation. Often this was spoken about euphemistically or off the record, but Julia Fawcett at the Lowry summed up a lot of these concerns when she said: “I think I’ve never seen such unease within the sector about what we can and cannot do, what we can and cannot talk about. That can’t be

a good thing.”

In the positive column, Arts Council England’s recently announced Incentivising Touring fund has been warmly welcomed and there is a genuine feeling that it could be transformational. Certainly, it feels necessary given the widespread concerns around the pipeline of touring product. Another trend that seems to have emerged amid concerns about the product pipeline is that a number of large-scale theatres are opening up, or have already opened, studio spaces in their buildings in a bid to help support independent artists to develop work. This is clearly a response to the challenges this sector is facing when not under the wing of a larger organisation.

The final theme – and for me the most surprising – was how often transport difficulties came up as a key challenge.

This was not completely universal and manifested in different ways, but nearly every theatre had some gripe about actually getting audiences to and from their auditoriums.

In Nottingham, the issue is that the final train out of the city is too early for evening audiences to get home to nearby cities and towns. In Cardiff, a newly installed cycle lane is causing coach-parking issues for school groups outside the Sherman. In Belfast, the issue is a lack of parking. ATG’s Julia Potts reported specific challenges for audiences in cities where councils are looking to – understandably – deter drivers, but haven’t improved public-transport infrastructure sufficiently to compensate. In Shetland, some audiences have to leave shows early to catch the last ferry home if they live on the most northerly islands.

In Truro, Hall for Cornwall revealed the potential upside of addressing these issues: an official at Cornwall Council recently helped convince the local train company to put on later trains between Truro and Falmouth, allowing students from the local university to get to and from the theatre.

“It’s the best piece of audience development we’ve ever done,” said chief executive Julien Boast.

Some geographical limitations, however, are just unavoidable. There was a final thought from Graeme Howell that might serve to put things in perspective for anyone pulling their hair out as another train gets cancelled or delayed.

“We’re part of an international collaboration of small music promoters,” he recalled. “I was moaning about transport to and from Shetland and a promoter from Alaska said: ‘Graham, it’s a 200-mile flight to get here. That’s it. There’s no roads. So what are you moaning about?’

“There’s always someone worse off than you.”

We have made this article free for everyone to read, but producing in-depth, nationwide coverage such as this depends on the support of our subscribers.

Without enough support, producing this kind of journalism is not possible.

If you value it, please help ensure its future by subscribing today—from just £7.99.

Long Reads

Recommended for you

Opinion

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £5.99