Edward Snape and Marilyn Eardley

Twenty-five years after founding production company Fiery Angel – now a sprawling family of businesses with offshoots ranging from children’s work to comedy to an investment fund – the husband-and-wife duo behind it all tell Tim Bano about what success, and failure, look like to them and why, despite the challenging landscape, commercial theatre in the UK is in rude health

Someone once asked Edward Snape and Marilyn Eardley, founders of production company Fiery Angel as well as husband and wife, if they ever talk about work at home. “We genuinely said: ‘No we don’t’, ” Eardley remembers, “and our kids fell on the floor laughing.” Snape adds: “They said we talk about it all the time. We don’t even notice we’re doing it. I guess it’s just become our life.”

The duo are sitting in the glass-walled meeting room of Fiery Angel’s offices near Holborn, surprisingly modern in an old stone building, where a rattling lift with metal grille door chunters its way to the top floor. Posters pick out a quarter of a century of successes: Kenneth Branagh’s year-long residency at the Garrick Theatre, The 39 Steps, Long Day’s Journey Into Night, Peppa Pig, Fleabag.

“London theatre has never been so good,” Snape reckons. “When we started, landlords would ring you up all the time and say: ‘Have you got a play?’ When we brought The 39 Steps into the West End, we were offered two theatres and an open-ended run. That would never happen now.”

“There used to be dark theatres,” Eardley adds. “Landlords just did not have the supply of work that they have now.”

Twenty-five years after Snape and Eardley founded the company, it’s now a sprawling family of businesses, encompassing general management, children’s theatre, comedy and entertainment and a multimillion-pound investment fund. And while each venture has to wash its own face – and ideally make money – the key for Snape and Eardley is that diversity.

‘There used to be dark theatres. Landlords just did not have the supply of work they have now’ – Marilyn Eardley

While Fiery Angel is a one-stop shop for producing, handling everything from creative development to general management, its sister organisations in the Fiery group specialise in various ways: Fiery Entertainment in music, comedy and dance, Fierylight in commercial work for young audiences, Children’s Theatre Partnership in subsidised theatre for young people and Fiery Dragons as an investment company.

That variety reflects the very different backgrounds of Eardley and Snape. “I was a working-class girl, the daughter of Irish immigrants,” says Eardley, who is often reluctant to be the public face of Fiery Angel, usually leaving the showmanship to Snape. “I worked behind the bar of the Lyric Hammersmith, then I started working backstage. Then two young actors came to the Lyric. They were setting up their own theatre company and were looking for somebody to help them. They both thought I was older than them, and had more work experience than I actually had.” The two actors were Kenneth Branagh and David Parfitt, whom Eardley helped to set up Renaissance Theatre Company, behind some of the most successful theatre productions of the late 1980s.

Continues...

Meanwhile, Snape jokes that he is always called the posh one and has to remind people of his background in literal end-of-the-pier entertainment: after a teen stint as Norfolk’s finest child magician Snippo, then as a Bluecoat at Pontins (“the poshest bingo caller they’d ever had”), the East Anglian impresario Dick Condon offered Snape a role managing a season at Cromer Pier when Snape was just 19.

It was in London a few years later that Snape and Eardley met: Snape had brought the Reduced Shakespeare Company into the West End and needed a general manager. “I went to a general management company and there was this very beautiful blonde lady.”

“Who looked about 10 years older than you,” Eardley jokes. “Even though we’re exactly the same age – just a few weeks apart,” Snape adds. “So we had a big success with that, and it was around 1999-2000 that we decided to start our own company.”

What’s in a name?

The name Fiery Angel, after the Prokofiev opera, owes itself to Snape’s parents, who were both involved in that world. “My dad was one of the founding directors of Sadler’s Wells Opera, which became English National Opera, my mum was an opera singer. And I thought Fiery Angel was a lovely name.”

It was never going to be Eardley and Snape Productions, or something along those lines? “It’s great having your own name on the poster, but I think we’re really proud of being Fiery Angel. It reminds us that it’s more than just one person. Thinking back on 25 years, all the people who’ve worked with us are the unsung heroes.”

Both of them were well established in the theatre world by that point. Snape had just been through the intense ordeal of working on the New Year’s Eve concert that marked the opening of the Millennium Dome (now the O2 arena) and the start of the new millennium.

Inside the not-quite-finished Dome was a concert for 14,000 guests, including Queen Elizabeth, Tony Blair and the Archbishop of Canterbury. It was Snape’s job to use a £4 million budget to book the artists, who included the Corrs, Annie Lennox and Mick Hucknall. The whole thing was being broadcast by the BBC to 800 million viewers across the world.

“Not many people knew at the time, but the IRA had issued a bomb warning. So we had three airport security scanners trying to get 14,000 guests into the Dome. I and a few other people were going: ‘We may not get this show up on time’, and you could not be late because midnight was not going to wait.”

Eardley had tickets to be in the audience with their infant daughter. “Because I had a buggy with a child and all these coats on it, I got to the security scanner and they said: ‘Oh just go around the side.’ I could have had anything in there!”

They also lost the Archbishop of Canterbury briefly: “Somebody said to me: ‘You might have to do the Lord’s Prayer,’ ” Snape remembers, “and I thought: ‘Please no.’ It was all quite tense.”

Continues...

Around the same time, their first child had just been born – “She was our little Fiery Angel as well,” says Eardley – and the pair decided that it was the perfect moment to work together and form their own company. “It gave me the flexibility to be a mum. I’d also been looking after some unwell people in my family, so it was very helpful for me to be able to work at different times. It was also the arrival of email. Suddenly it was easier for mums to work because, once you put the kids down, you could reply to people, instead of trying to catch them on the phone at the right time. That really changed things a lot.”

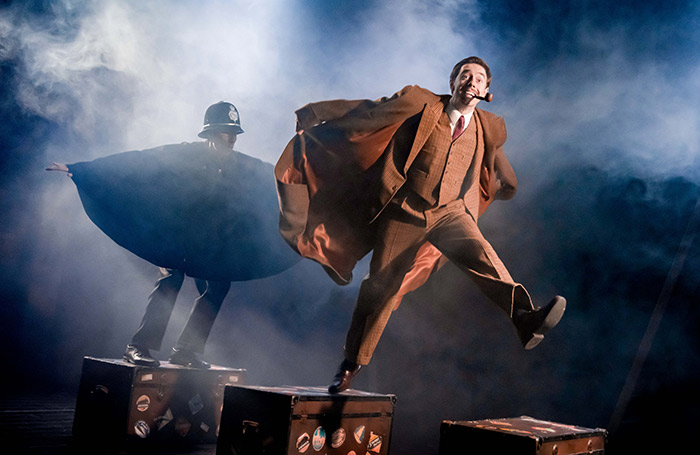

The early days were hard, but amid the financial stresses they helped reopen the Arts Theatre, toured Five Guys Named Moe, and had successful shows for young people such as The BFG – already an indication of the variety of work that was to come. But it wasn’t until 2005 that things began to settle, when Patrick Barlow’s comedy adaptation of The 39 Steps went into the West End after years of development, and then found popularity internationally, too. There was a year, Eardley points out, when Barlow was the most performed playwright in the US apart from Shakespeare.

“Our 30s were quite stressful at times,” she says. “The 39 Steps gave us stability where we knew that we could pay the wages, pay the office, and start developing new projects as well.”

Dealing with ups and downs

While the successes have been plentiful, not everything has been a hit, of course, and losing money is something Snape takes very personally. “I really hate it.” So what do success and failure look like to the pair? Is it just about the money? “There are plenty of shows that we’ve been proud of… and that haven’t worked,” Eardley says. “We co-produced [the West End transfer of] The Son by Florian Zeller, and that was a production we were very proud of, a critical success, but it did lose a lot of money. Then there are the shows that are neither critically nor financially successful, and the audiences aren’t interested in. Those are the very painful ones.”

How do the couple deal with those big losses? “Very badly,” laughs Eardley. “You still feel it in your gut,” adds Snape. That’s when it helps that they’re a couple. “We tend to dip at different times,” says Eardley. “If Ed’s feeling it, I’m generally more optimistic about things, and vice versa.”

And for Snape, an absolutely vital quality in being a producer is telling people the bad news even faster than the good news. “Woe betide any producer who is slow in producing bad news. We believe that you have to tell investors the truth.” Especially, he points out, when the amounts people are putting into productions are getting bigger. Theatre is a lot more expensive to make than it used to be – which is part of the reason they’ve set up a new investment fund called Fiery Dragons II.

‘Woe betide any producer who is slow in producing bad news. We believe that you have to tell investors the truth’ – Edward Snape

Fiery Dragons started in 2011 with around £1 million and has since invested around £7 million in more than 240 productions. Those tended to involve individual investors putting money behind individual shows. Fiery Dragons II is about putting money into a fund – not unlike traditional investment funds – that fund managers then spread across a portfolio of productions.

“A lot of investors enjoy betting on the horse,” Snape explains, “whereas this is more betting on the stable. Compared to Broadway, it’s still modest sums of money, but it’s more of a longer game than putting money on one show.” What kind of sums are they dealing with? “I think the largest investment we’ve put in on a project is probably a quarter of a million or something like that. But it’s quite often quite a lot smaller than that.”

Of course, for producers, success and disaster aren’t always about money. Sometimes it’s just bad luck. Just a few months ago, a flood forced them to cancel a performance of new musical Kathy and Stella Solve a Murder! halfway through the show. It didn’t help that it happened to be press night. “Then there was the time we lost two Romeos in one week,” Eardley remembers. During Branagh’s takeover of the Garrick, there was a production of Romeo and Juliet that was meant to star Richard Madden and Lily James. While out jogging one day, Madden badly hurt his ankle; no problem, his understudy Tom Hanson stepped in the next day. Except during a fight scene, Hanson managed to injure his leg. “That was the only time we’ve cancelled shows,” says Eardley.

Continues...

Q&A Edward Snape and Marilyn Eardley

What was your first non-theatre job?

Snape: Newspaper delivery boy for about two weeks. A magician was better paid.

Eardley: I didn’t have one.

What was your first theatre job?

Snape: Magician at children’s birthday parties (from age 11).

Eardley: Bar staff at the Lyric Hammersmith.

What do you wish someone had told you when you were starting out?

Snape: To work as an apprentice for a producer. Stage One didn’t exist when I was young.

Eardley: Don’t do it! Just kidding. Stress less.

Who or what is your biggest influence?

Snape: Richard Condon, who ran Norwich Theatre Royal and let me loose to run an end-of-the-pier show aged 19.

Eardley: Kenneth Branagh.

What is your best advice for auditions?

Snape: Your talent is why we are all in business.

Eardley: I hate to hear actors have a negative experience in auditions. I think the onus is on producers, directors and casting directors to put actors at ease so they can do their best work.

If you hadn’t been a producer, what would you have done?

Snape: I have absolutely no idea.

Eardley: I’ve no idea. I’m not qualified to do anything else. In a fantasy world, I fancy myself as a doctor – a different type of theatre.

Do you have any theatrical superstitions or rituals?

Snape: I often avoid green on posters. Sheekey’s for pre-show drinks.

Eardley: I have more superstitions than I’m prepared to admit.

Snape remembers “going into the dressing room and Derek Jacobi, who was playing Mercutio, said to me: ‘Who’s going to be Romeo tonight?’ And I was thinking: ‘I have no idea.’” Brains were racked, heads put together, and someone pointed out that Freddie Fox had recently played Romeo in Sheffield, so he stepped into the production and the show went on.

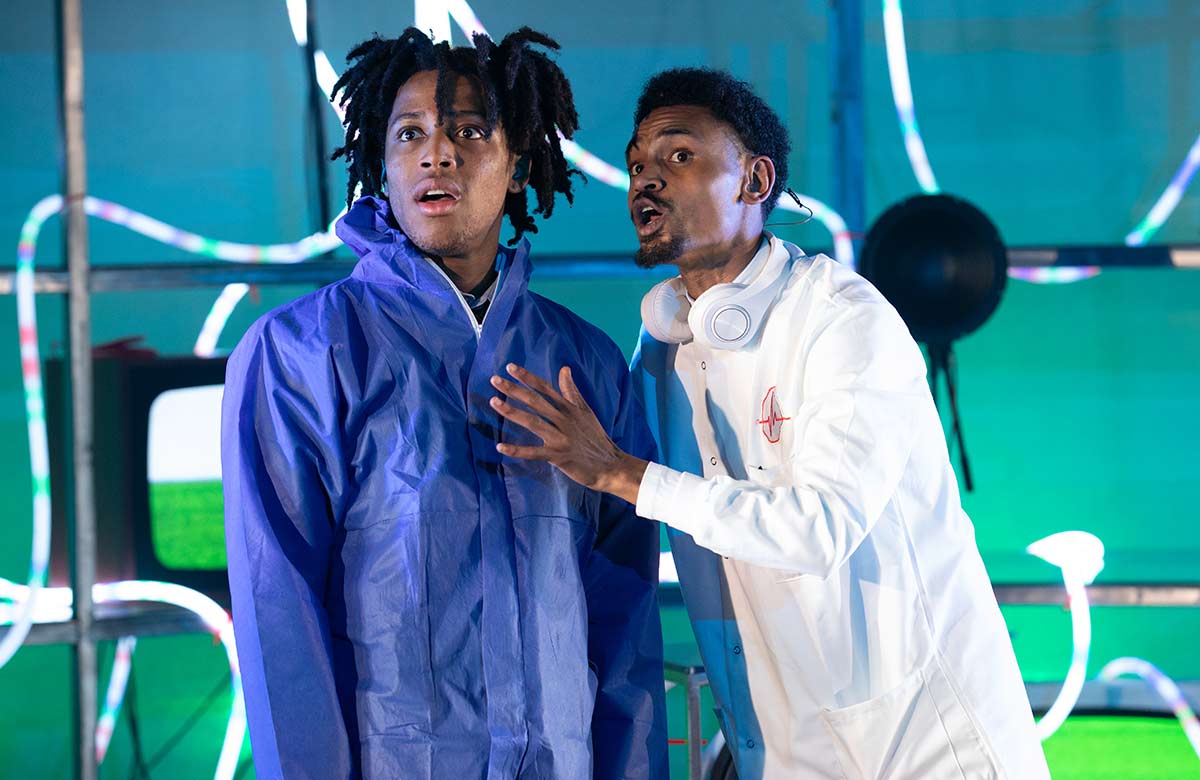

But when it all goes right, there’s no feeling like it. “It’s like an addiction,” says Snape. Last month, he went to see Winsome Pinnock’s adaptation of Malorie Blackman’s Pig Heart Boy at the Unicorn Theatre, one of the shows that Fiery Angel is producing as part of the Children’s Theatre Partnership. “Oh my goodness, if that wasn’t a great show, and a truly diverse audience, and I just couldn’t be prouder. That, to me, is just as much success as a commercial financial hit.”

Positive change

What, then, are some of the big changes the pair have seen in 25 years of commercial producing? For an organisation that’s “as passionate about regional as we are about London”, the landscape for touring is incredibly tough, Snape says. “Local authority funding has really dropped back, theatres used to be the hub of the community, and it’s really tough that loads of them don’t have the money. If you go back 25 years, most management companies would have received a thing that just doesn’t seem to exist now, particularly mid and large-scale touring, which is a guarantee. You’d get a guaranteed income across a run. Now, you would very rarely get that.”

And while costs have risen hugely in 25 years, one big positive change is Theatre Tax Relief. “It’s a game changer,” says Eardley. For Snape, “we used to say when it first came out that it was the icing on the cake. Now it’s the cake.”

‘We want to partner more with younger producers. It’s really exciting to work with people who have different ideas’ – Edward Snape

They argue that it allows producers to take risks on new work, and to make it at scale, but it has also regulated the finances of the industry. “Everyone is now sending their accounts to HMRC, whether you’re a not-for-profit or a commercial producer, and everything needs to be transparent. That’s been quite a shift, from the old school, maybe not quite as transparent, to now where it really is, because you know someone from HMRC is going to be looking at it.”

So what do the next 25 years look like for the Fiery group? “We want to partner more and more with younger producers,” says Snape. “It’s really exciting to work with people who have different ideas, and we can learn from each other.”

Where theatre producers in years gone by might have been much more competitive and adversarial, there’s an increasing collegiality among them these days. Fiery Angel works with other independent commercial producers such as Eleanor Lloyd and Francesca Moody, general managing the West End run of Fleabag and co-producing Kathy and Stella Solve a Murder!. “We’ve always had producers we’ve got on with,” Eardley says. The difference now, Snape adds, is that there are fewer available theatres and “it’s better to have a slightly smaller share, and to cosy up with other people”.

Besides, they say, at some point a stepping away has to happen. “It would be nice if one day there were young people running Fiery Angel,” Snape says.

“Although you’ll keel over before you retire,” Eardley points out. “I don’t know what I would do with Ed if he didn’t have 200 plates to spin at any one time.”

For more information, visit: fiery-angel.com

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99