Power of performance: How Freedom Theatre makes work in the West Bank

A decade since the violent death of Freedom Theatre’s Juliano Mer-Khamis, director Zoe Lafferty gives a personal account of her work with the company in Jenin refugee camp – explaining the company’s mission to put Palestinian experiences on stage, recalling a controversial tour to the UK and cancellation in the US, while looking towards its increasingly uncertain future

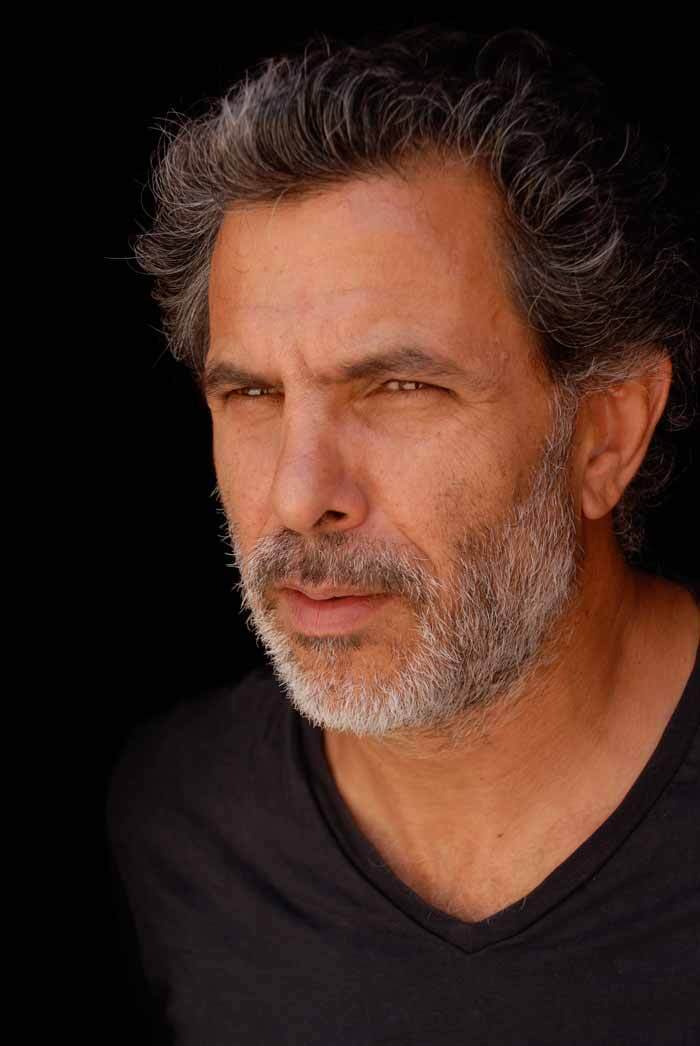

It is 10 years since a masked man and five bullets took the life of actor and director Juliano Mer-Khamis outside the Freedom Theatre in Jenin refugee camp, West Bank, where he was artistic director.

Just weeks before, we were riding the high of opening a new production, Alice in Wonderland, that I had co-directed with Juliano. We enjoyed the adrenaline rush as audiences packed the auditorium, and the actors became local celebrities. It was a radical adaptation with a revolutionary message, challenging dictatorship, patriarchy, corruption and Israeli military occupation.

It was a show that held the core values of cultural resistance that the Freedom Theatre was becoming famous for. Founded in 2006 by Juliano alongside Zakaria Zubeidi, then leader of the armed resistance, its mission was both to build back Palestinian identity destroyed by years of brutal occupation and tour the often unheard, first-hand experiences of Palestinians to the international community.

Juliano’s radical vision of a political and artistic movement of artists who would raise their voices against discrimination was beginning to create a ripple of change both locally and worldwide. “Make sure you listen carefully and watch every moment… It will be our biggest scandal yet,” Juliano said, teasing the audience at the premiere of Alice.

The theatre’s moment of triumph turned into a nightmare, beginning a 10-year battle to keep its doors open

Then, a week after the shows had finished, on April 4, 2011, Juliano was murdered outside the venue – the theatre’s moment of triumph turned upside down into a nightmare, beginning a 10-year battle to keep its doors open.

Before Juliano’s murder, it was hard to grasp his vision that fighting for Palestinian liberation through the international language of theatre could achieve the same aims as an armed struggle. Now the immense power and danger of theatre, in fighting an oppressor, was clear. Soon after the funeral we went back into rehearsal. But as our will to continue Juliano’s legacy grew, as did the determination to break it.

We received anonymous deaths threats creating a paralysing fear that there might be another assassination. Then the Israeli army attacked the building with rocks, strategically arresting four members of staff, holding them in prison without access to lawyers and subjecting them to intense interrogation.

Six months later, paranoid, overwhelmed and exhausted, we toured Europe with a new show filled with the rage, grief and madness reflective of our most recent experiences. We went from village halls, to opera stages to Berlin’s Schaubühne, losing a couple of the team to visa issues and colliding with audiences who questioned: “Where is the hope?” Our group passionately answering: “Hope is that we are here and continuing”, a statement often received with a standing ovation.

The Freedom Theatre continued to open new shows in Jenin refugee camp, introducing new audiences to theatre, who saw themselves reflected in the performances and felt heard. Young actors who had often never travelled outside the West Bank now performed on stages in every continent, amazed that audiences would pay money and then sit quietly to hear their stories.

A new generation was trained in cultural resistance and learnt the power of performance as a tool to fight for justice and equality. But as the theatre grew in strength it was always shadowed by fear and exhaustion from the continuing obstacles and the stark reality that no performance can stop an occupying army. Actors would be refused visas, often there would be interrogations at borders and then Nabil Al Raee, who had taken over as artistic director, was visited in the night by the Israeli Army and arrested for 40 days, suffering the violent psychological effects of imprisonment.

In 2015 we planned to tour across the UK, an important milestone for me as a British director. Working with Juliano had shaped my understanding of theatre’s role in the fight for social and political change. His death was a constant reminder of what he had sacrificed for those beliefs and the responsibility we now had as artists who collaborated with him.

A few days before the opening, the Daily Mail went after the production, claiming we were promoting terrorism. We performed our first show, which was supported by Arts Council England and the British Council, at the Lowry in Salford with protests outside, the auditorium surrounded by security and a plan of how to evacuate the actors off the stage if they were attacked.

A vicious media campaign and protests followed us around the UK, and we toured under the constant threat that the show would be closed down. In an extraordinary moment of solidarity, theatres, funders, activists and human-rights lawyers came together and fought for the show to go on, selling out across Britain. Later that year, the same production would be cancelled by the Public Theater in New York.

Ten years after Juliano’s murder, the Freedom Theatre’s situation continues to be precarious. Due to Covid, the one border to enter or exit the West Bank has been closed for more than a year and so for a theatre whose survival is dependent on international touring and solidarity, it has been mercilessly isolating.

Online we continue to collaborate, creating a new project, The Revolutions Promise. It tells our own story as well as of artists across Palestine who have been censored, silenced and attacked including the bombing of Said al-Mishal Cultural Centre in Gaza, and the imprisonment of poet Dareen Tatour.

Recently the Freedom Theatre, along with multiple other cultural venues, refused new conditions set by their major funders in the EU. The conditions demanded specific political positions, including condemning the actions of the Palestinian resistance and certain political groups.

We felt it was a direct attempt to silence the Palestinian arts sector, limiting the artists they worked with and censoring the narratives they speak about. By refusing the conditions, the Freedom Theatre consequently lost most of its funding – a devastating blow at any time but particularly during a pandemic.

For a theatre whose survival depends on international touring, Covid has been mercilessly isolating

Ahmed Tobasi, one of Juliano’s students, has taken over as artistic director. A former member of the armed resistance and previous political prisoner, his personal story is one that echoes both the armed and cultural struggle that is inherent in the DNA of Palestinians from Jenin refugee camp.

He knows first-hand the limited options for young people growing up with no way to escape the continued violence. “Juliano gave me the understanding of how to question the world and its power structures, our society, the corruption of the Palestinian Authority, Israeli occupation and, through cultural resistance, face this life, my community and my oppressors. To fight for children, women, justice and equality and lead the Freedom Theatre as it continues to be an alarm for all the difficulties of humanity.”

Tobasi regularly talks about how theatre gave him a way to fight that would not lead to death. However, with one artistic director murdered, another imprisoned and countless staff and students arrested, it is not a case of if he is in danger but simply how severe the punishment will be for daring to dream. “Yes, it is dangerous. But exactly as life is the most valuable thing to have, death is the most valuable thing you can give. And this is what we must accept as artists in Palestine,” he says.

See the Freedom Theatre website for further details

Opinion

Recommended for you

Opinion

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99