Paving the way: the fragile legacy of Covent Garden street performance

Covent Garden’s piazza has been a starting point and a place of development for much of our home-grown talent, but some believe its future is uncertain. Performers and campaigners tell us why this unique setting must be preserved

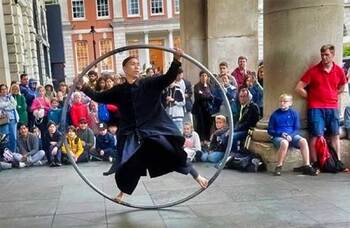

Since the 17th-century diarist Samuel Pepys wrote about a “very pretty” puppet play he had seen – the first recorded sighting of a Punch and Judy show – in Covent Garden nearly 400 years ago, the area has been the epicentre of street performance in London.

Tourists still flock to see magic, circus, comedy and a host of other shows in its piazza. From Charlie Chaplin to Eddie Izzard, some of entertainment’s biggest names have started out in front of Covent Garden’s crowds. It’s even said that former James Bond Pierce Brosnan once had a fire-eating act there.

But today, many feel that Covent Garden’s identity as a vibrant performance space is under threat. In 2021, Westminster City Council’s licensing sub-committee introduced a new policy to regulate street performance throughout the London borough after saying it had received approximately “1,800 complaints each year about excessive noise or overcrowding caused by busking”.

In addition to Covent Garden, popular performance sites covered by the policy also include Leicester Square and Trafalgar Square. The resulting Busking and Street Entertainment policy includes a stringent new code of conduct focused on performance size and duration, and prohibits features such as “naked flame, pyrotechnics, fireworks, knives and sharp objects”.

If the crackdown continues, it would mean the slow death of Covent Garden street performance through red tape – SPA spokesperson Peter Kolofsky

All applicants for a performance licence must have public liability insurance of at least £2 million, while it costs £40 every six months to renew a licence (with a discount of 50% available for students).

Towards the end of last year, the council announced it would start cracking down on performers breaking its rules, leading to a stand-off with the non-profit organisation Covent Garden Street Performers Association, which supports and promotes the art form.

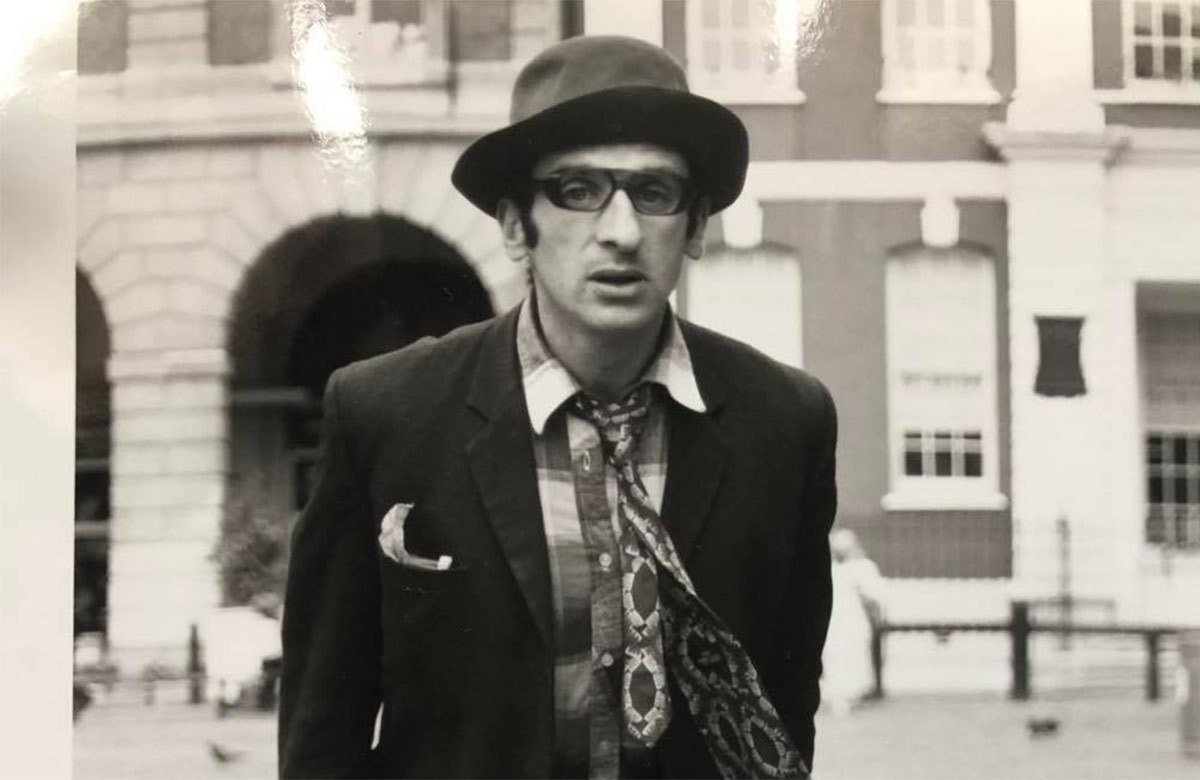

“You’ve got Big Brother coming to interfere in a situation where there’s no problem,” says SPA spokesperson Melvyn Altwarg, who studied clowning at the Ecole Philippe Gaulier in Paris and performed in Covent Garden from the early 1980s until his retirement.

He flags a host of issues with the policy’s restrictions: for example, on knives: “They’re not dangerous, they’re circus props.” Besides, he says, the SPA, which describes itself as facilitating a self-regulating community of performers that, has “lots of rules” when it comes to health and safety. Fire is already banned “because it’s too risky” and there is a penalty system in place for noise.

“If the licence was enforced, it would mean the slow death of Covent Garden street performance through red tape,” says fellow SPA spokesperson Peter Kolofsky.

He has been drawing crowds with acts such as knife-juggling in the piazza for more than 15 years. Footage from one of his performances has attracted 30 million views on YouTube.

He sees the regulations as incompatible with reality.

“We would be restricted to a five-metre-diameter performance space,” he says incredulously.

Altwarg also says that if the licence system was enforced, it would impact performances by international artists who play Covent Garden as they pass through London. “Last year, we had six Japanese performing groups,” he says.

“They were working on the west of the piazza. It was fantastic. But they’d no longer be able to do that.” This internationality is vital, he says, for tourism and culture. “It brings new energy and things we haven’t seen. It links us with the world.”

Continues...

So, as far as the SPA’s 100-strong membership is concerned, the policy is unnecessary and fundamentally unworkable. Its members have refused to apply for the licence, arguing that self-regulation has worked perfectly well for many years, and that noise complaints are far more applicable elsewhere in the borough.

While the council did not respond to specific questions asked by The Stage, it reissued an earlier statement from Aicha Less, deputy leader and cabinet member for communities and public protection, who said: “The busking and street entertainment policy was introduced two years ago to preserve the tradition of live street entertainment in Westminster, which is hugely popular with visitors, and to ensure busking and street entertainment operates in a safe and responsible way.”

At a meeting in December, the council’s licensing committee agreed to a public consultation before deciding the policy’s future. The consultation date has yet to be announced.

“We had, of course, hoped that Westminster Council might make moves to exclude Covent Garden from the licence, as we have been campaigning for,” SPA said in response, describing the consultation agreement as a “temporary win”.

Maggie Pinhorn, director of Alternative Arts, which champions accessible cultural events, shares Kolofsky and Altwarg’s view that the council’s plan ignores the critical distinction between circus, theatre or comedy acts performed in the unique space of Covent Garden and busking around the crowded streets of Leicester Square and Oxford Circus.

“It fails to appreciate or understand the history of Covent Garden street theatre,” she says.

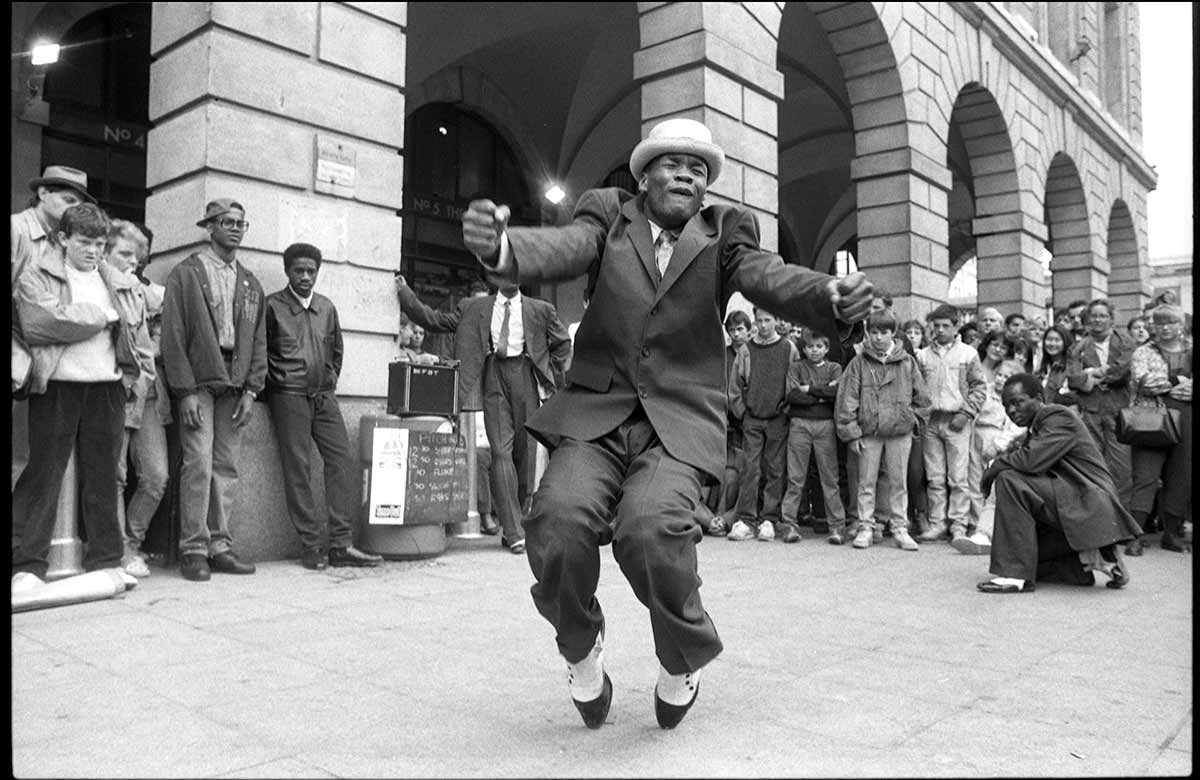

Pinhorn helped to turn Covent Garden into the performance space people know today. She staged the first street theatre season in 1975, with the permission of the then Greater London Council and St Paul’s Church – known as the Actors’ Church – when the fruit and vegetable market moved out of the piazza.

She would book “fantastic community theatre groups”, promote them as lunchtime events in Time Out and watch people turn up for the show with a copy under their arms, “a packet of sandwiches and a glass of beer”.

Covent Garden is one of the last places in the UK that young performers can make a living –

Comedian Stuart Goldsmith

Through Alternative Arts, she still runs the Covent Garden May Fayre and Puppet Festival each year.

The piazza is “a natural theatre space,” says Pinhorn, who originally trained in set design. “The portico of the church is the proscenium arch. It conforms to all the Brechtian conditions of theatre.”

She contrasts this with Leicester Square, which is “full of buskers fighting for space. You can’t perform acts like balancing or tightrope walking safely there. But you can in Covent Garden”.

She feels strongly that it should remain independently regulated. “It’s unlike any other busking pitch, because it features remarkably skilled performances,” she emphasises.

“People go there specifically to see them.” For this reason, Covent Garden “needs the special protection of the SPA”, says Pinhorn. “[Its members] have the knowledge and experience.”

And the SPA is always exploring how to bring in “new blood”, Altwarg adds. “We’re talking with the National Centre for Circus Arts about some of its performers coming to work on the west piazza.”

This builds on a legacy of acts such as Martin ‘Zippo’ Burton, who begun his career in Covent Garden before founding the internationally renowned Zippos Circus.

Performances range from clowning to card tricks to stand up, but on the piazza’s open-air stage, “if you do a good show, you can make a living”, says Altwarg.

Mark Rothman is one of many comedians who started out performing in Covent Garden. He brought his act to London after honing his skills in Australia and Japan. He would go on to establish the Top Secret Comedy Club, now on Drury Lane.

He is passionate about maintaining the uniqueness and independence of Covent Garden as an environment where acts that are just starting out can develop, experiment and really hone their skills.

“You learn in a far more visceral and real way than you do at school,” he says, including how to hold the attention of a crowd that may just be passing through. Without that front-line training, he says: “I wouldn’t have a comedy club now.”

Continues...

He also believes there is a lack of understanding from Westminster Council about the value of street performance – he thinks its “presiding world view” is that “art should be in galleries and theatres, not outside”, and questions its claims of having consulted with the performers.

Rothman contrasts this with his experience of the Busk in London project, a Mayor of London-backed initiative set up in 2015, whose organisers met with performers across the city in order to produce a busking code of conduct.

“It was so good,” he says. “They had guys who were monitoring volume levels, where complaints were coming from and what time – and naming the people who were causing the problems.”

According to Kolofsky, there is a strong sense of loyalty and mutual support between past and present Covent Garden performers. “For all intents and purposes, the SPA functions like a union.” While there’s even a benevolence-style system in place to provide performers with support if they fall ill or become injured, Altwarg explains.

“If someone can’t perform, we’ll do some shows to raise some money to help them out.”

There is a sense of charity baked into the ethos of Covent Garden performance, too. The SPA has also hosted events in partnership with the various charities it supports; street performers have raised funds for Ukraine on behalf of the Red Cross; Izzard performed a special show for homeless charity Crisis and in June 2022, Michael Palin read Peter and the Wolf in Covent Garden, joined by an ‘orchestra for peace,’ whose members included Ukrainian refugees. It is far more than just a busking site.

Comedian Stuart Goldsmith is one of Covent Garden’s many success stories. He thinks it is “one of the last places in the UK that young performers can make a living while learning skills that will contribute to the cultural landscape and economy”.

Speaking of his own career, which has seen him perform at Wembley Arena and work on The Graham Norton Show, he thinks that “none of it would have been possible without the hours and hours I spent developing my work on the west piazza”.

Similar to many others, Goldsmith sees Covent Garden as a key part of London’s ecology. The street theatre there is “like a forest in a city,” he says.

“Chop it down to make way for more commerce and the city will gradually asphyxiate and die.”

Opinion

Recommended for you

Opinion

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99