Insulted. Belarus(sia): The protest play laying bare the harsh realities of the Belarusian revolution

As Belarusian playwright Andrei Kureichik’s play about the first month of the ongoing events in Belarus since the contested presidential election in August takes centre stage, Natasha Tripney finds theatres around the world are showing solidarity

Belarus is often referred to as “the last dictatorship in Europe”. Since August, there have been mass protests against its president Alexander Lukashenko – who has been in power for 26 years – after his re-election this summer was broadly rejected as fraudulent. Rallying round opposition candidate Svetlana Tikhanovskaya, the people refused to accept the result and week after week took to the streets in protest. These peaceful, often female-led protests were brutally put down. There were multiple arrests. People were injured, many severely. There were deaths. Those who were arrested told tales of inhumane treatment, beatings and sexual assault.

The resistance did not dissipate. The protests spread to the institutions, the universities, health facilities and factories. More than 100 days later and the protests show no signs of stopping. In the last weekend in October, 200,000 people flooded into the Belarus capital, Minsk, for one of the biggest demonstrations since the election.

Now a play written in the first weeks of protests has become the basis of a global gesture of solidarity. To date, there have been readings of Andrei Kureichik’s Insulted. Belarus(sia) at 69 venues in 21 countries. The play has been translated into 18 languages, including Cantonese, Pidgin and Yoruba, and the numbers are climbing.

Continues...

Back in September, Kureichik, a member of Belarus’ Coordination Council for the transition of power, wrote the play as a rapid response to those first days of protests, arrests and violence meted out by the police. He wrote it quickly, capturing the urgency of the situation and went into hiding immediately after finishing.

He was right to be fearful. The regime has often targeted and imprisoned artists. The co-directors of Belarus Free Theatre, Natalia Kaliada and Nikolai Khalezin, have been forced into exile in London for a decade while their company continues to perform underground in Minsk in order to avoid arrest.

“Lukashenko hates artists, because most of them are free and independent people,” Kureichik says. Under Lukashenko’s regime, theatremakers, poets, musicians and writers were all targeted. “A lot of them are in prison even now. Hundreds of them were punished with arrests and fines or were fired. And his hate is based on the power of art.” Dictators like Lukashenko fear that power.

‘Lukashenko hates artists, because most of them are free and independent people. His hate is based on the power of art’ – Playwright Andrei Kureichik

Kureichik believes, however, that something fundamental is changing in Belarus. The protests have persisted because people have woken up. “New generations no longer want to live in a pseudo-Soviet country, with all this Soviet aesthetics, terrible laws, constant abuse of civil rights and closed borders to civilised countries,” he says.

Lukashenko’s Covid denial has also played a role. “His attitude to people was so bad, that when thousands of Belarusians died because of Covid, people said that we don’t need a person [in power] who doesn’t care about people’s lives.”

He feels the country will never be the same after this. “I believe the system will change and Belarus will become a democratic country.”

Continues...

Kureichik sent his play to John Freedman, the former critic for the Moscow Times, asking him if he would be interested in translating it and, maybe, also arranging some readings.

Freedman contacted some colleagues about the project to sound them out and within minutes they all agreed to participate, which meant he then had to translate the play quickly. He did this in three days, a record time for him. By the time he sent the play out to interested parties, more theatres had agreed to arrange readings. “The project just exploded and took on a life of its own,” Freedman says.

Before long, strangers were writing to him asking if they could take part. “In a few cases I learned after the fact that someone had just taken the play and done their own reading without contacting me. I think I have caught up with most of them, but there may be events taking place out there, about which I know nothing.”

With protest movements, there is always a danger of outrage-fatigue setting in internationally, of the world’s attention turning elsewhere, especially in this turbulent year. A project like this helps keep the plight of the people in Belarus alive in people’s minds.

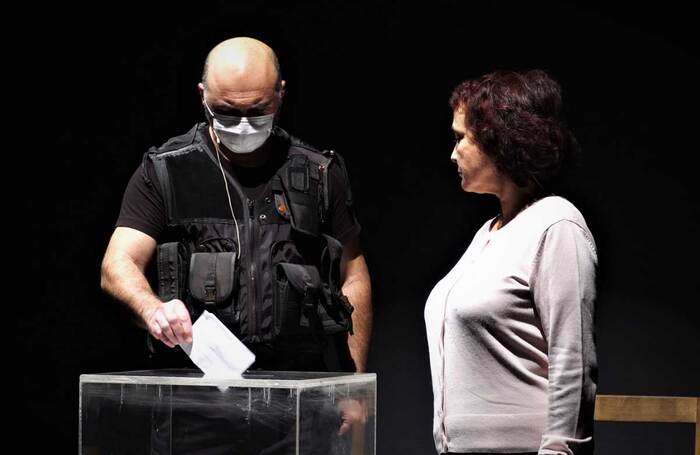

Kureichik’s play explores that first month of revolution. All the characters are based on real individuals: some in power, others who have pitted themselves against the regime, often at great cost. “I think what is happening in Belarus is a warning that we need to take notice of,” Freedman says. The play has a malleable quality that makes it perfect for a project like this. “It can take on the form anyone wants to give to it.”

‘What is happening in Belarus is a warning we need to take notice of’ – John Freedman, former Moscow Times critic who translated the play

The readings have been performed by theatres and universities, mostly via Zoom or Facebook Live, but in a few instances there have been live readings with socially distanced audiences, including one at the Royal Dramatic Theatre of Stockholm.

A number of theatres plan full productions when this becomes possible. In Ukraine, this has already happened with the Kherson Regional Academic Music and Drama Theatre putting on the fully staged world premiere on October 1. A film version, directed by Russian actor and director Oksana Mysina, premiered on Russia’s TV Rain earlier this month.

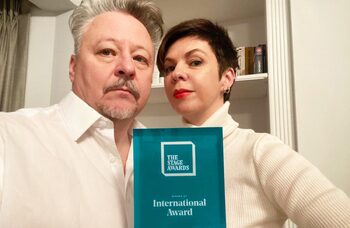

Olya Petrakova and Bryan Brown, the co-founders of ARTEL (American Russian Theatre Ensemble Laboratory), who both teach in the drama department at the University of Exeter, were among the first people to whom Freedman reached out. They immediately knew they had to get involved.

Continues...

“Our occasionally overwhelming daily struggles seem paltry in the face of peaceful protest against a heavily aggressive and militarised dictatorship,” says Brown. “Being involved in this project felt like an important action to get outside of our insular, lockdown-induced worlds and do something for others risking their lives for values we hold dear.”

The first UK reading of the play took place with Maketank, the ‘cultural lab’ run by Petrakova and Brown, on September 19, with a further reading on November 3.

Brown viewed the project as an educational opportunity both for his students and the wider world. “I thought being engaged with this kind of event might bring in an entirely new audience for raising awareness about the situation in Belarus, one that not only could effect changes in young minds, but also could have potential political leverage.”

These readings amounted to even more than the perfect way to continue to raise awareness of the situation in Belarus, says Brown: “They remind citizens of the power of theatre during a time when theatre and live performance was not only nearly impossible to attend but being actively dismissed by the [UK] government”.

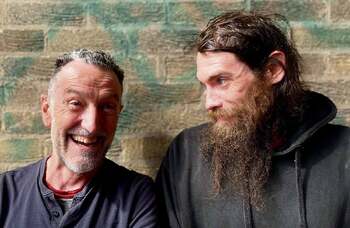

William Galinsky’s company, GalinskyWorks, staged a reading of the play in October, with performers including Tim Crouch and Eimear McBride. Galinsky was familiar with Freedman’s work from his time as a drama student at the Moscow Art Theatre School in the 1990s. He describes Freedman’s book Moscow Performances as “a roadmap to post-Soviet Moscow theatre”.

Galinsky hopes that having people like Crouch and McBride involved would ensure the play got on “a few more people’s radar”. This is crucial, as the situation in Belarus remains volatile. Recently, peaceful protestor Raman Bandarenka died from injuries sustained when he was assaulted by security forces, and pressure is building on the EU to extend its sanctions against the regime.

“I think trying to break through with a political issue like this to a wider audience is a type of activism,” says Galinsky. “The more people become aware and angry about this, the less easy it is for people and politicians in the West to turn a blind eye to it.”

New Perspectives Theatre will read Insulted. Belarus(sia) on World Human Rights Day, December 10

Opinion

Recommended for you

Opinion

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99