Back on the front line

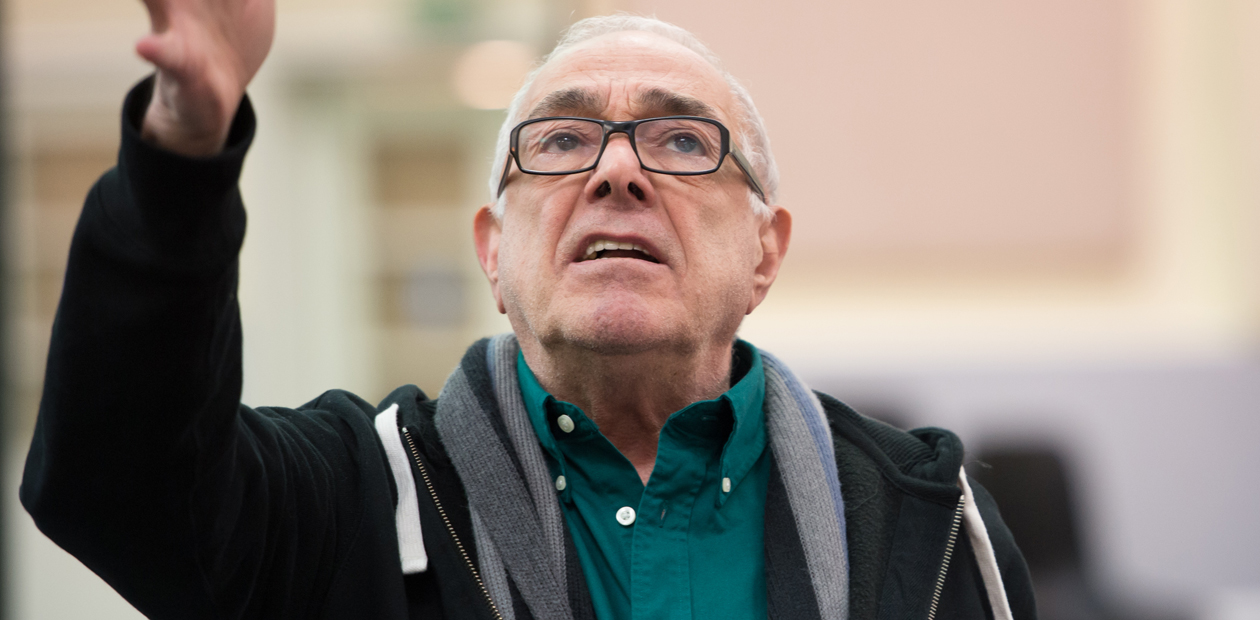

It’s been 12 years since Bob Avian’s creative touch has caressed the West End stage. Twelve long years. Back then he was choreographing The Witches of Eastwick musical, and if you’d asked him after his stint on that show what he was planning on doing next, he’d most likely have told you he was done. Finished. Leaving the theatre world for good.

Because Avian, then already in his 60s, was tired – exhausted – both physically and mentally.

“After that I did not really want to work any more,” he says. “Every time you do a musical it’s like pushing a boulder up a mountain. They hire you for what you’ve done, and what you’re known for, and then the moment they hire you they tell you what you should do. When you don’t have the passion anymore, or the hunger, it gets harder, and it all becomes so exhausting and so difficult. You have to have the hunger to survive all that.”

Evidently Avian has that hunger, however, as when we meet in a cafe on Tottenham Court Road in London, we are just yards from where rehearsals for the new West End production of A Chorus Line, which he is directing, are taking place. Now 75, Avian has decided to push that boulder up the mountain once more. The question, more than a decade on, is why?

“Sometimes shows come up, events come up, or A Chorus Line comes up and you have got to do it,” he says. “You have got to protect the product.”

That Avian should want to protect A Chorus Line is a no-brainer.

[pullquote]At the end of the show, my mother thinks they all got the job, and she is so happy. But what you are really seeing is that these dancers have worked so hard to be totally anonymous. That is the double power of the finale[/pullquote]

He worked on its creation with Michael Bennett back in the early 1970s, seeing it open first on Broadway in 1975 and then in the West End, in 1976.

He is billed as co-choreographer of the original, but has since moved on to directing the show, most notably reviving Bennett’s 1975 production on Broadway in 2006.

Now, he’s about to do the same in the UK, more than 30 years since the show was last seen by London audiences, with the musical set to open this month at the London Palladium.

For fans of the show, it’s been a long time coming. So what, I wonder, took him and his team so long?

“We have wanted to do it for a while, but because of the nature of the staging, and the way we have the line on stage, the musical demands a 40ft proscenium opening,” he explains. “I guess we could do it smaller, but all the choreography and staging is based on a 40ft opening.”

Originally, Avian says, the show played at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, which is of a similar size to the Palladium. There are only a few other suitable venues of that size, so the production was always dictated by what theatre was available. “And every time a theatre became available it was too small,” he says.

Happily, after years of waiting, Avian and his producers were able to nab the Palladium.

And when we meet, rehearsals are in full swing. Avian excitedly tells me about his cast, which includes Scarlett Strallen, fresh from Singin’ in the Rain, EastEnders’ John Partridge and Leigh Zimmerman, known to UK audiences for her appearances in Chicago, The Producers and dance show Contact.

“I am thrilled with the cast,” he beams. “I was afraid for a long time that we cast it too quickly, but I got to see the cream of the crop and I am thrilled with them. Everybody is so strong, and what I love about this company is they sing so well, which is always a plus.”

Why was he concerned about the speed of casting? He explains he came to the UK in November last year to see the best five people for the roles, and that, when he returned to the US, casting had not been completed.

“So we did some of the auditions, especially for the understudies, on video,” he says. “And the crew did a beautiful job of sending me these auditions, which the performers did in costumes. It was the first time I had done anything like that, but it worked. I wasn’t quite sure what the performers’ bodies would look like and I kept thinking ‘I am taking a gamble here’. But it was all pretty good in the end.”

A Chorus Line focuses on a group of dancers auditioning for a musical. It is set on the bare stage and the show provides a glimpse into lives of the performers as they describe events that have shaped their lives and why they chose to become dancers.

“Michael always wanted to do a show about dancers,” Avian says. “And the title came from a play he had directed previously called Twigs, by George Furth. The play was originally called A Chorus Line, and when he did it, Michael said to George, ‘I don’t think that title is suitable, but can I have it? One day I will use it’.”

And use it he did. The musical took a year to create, and had four workshops of six weeks each. Some of the workshops were taped, and performers who were used in these are still paid today.

One of those involved with the show from the start was Baayork Lee, who played Connie in the original production and whose own experiences, it has been reported, formed the basis for the role she played. Lee has since directed the show herself around the world, and is in London with Avian to prepare the production for the West End. However, this time she is taking care of the choreography, recreating the steps Avian first designed.

Avian says that he likes to direct the show when it is for a “major market”, such as Broadway or London.

“We have what we call a bible for the show,” he reveals. “But with every production we adjust it somewhat. The choreography is always locked in, but the individual performances – when I direct it – I like them to be their own. I don’t lock them in. I like the performers to create it, but they have to deal with the parameters of the story telling.”

Of course, Avian has seen plenty of productions of the show he has not been involved with, such as tours or small regional productions.

Some are good, others less so.

“I’ve seen it done in a lot of people’s hands,” he says. “Sometimes they get it, sometimes they don’t know what they are doing. I saw it in a little summer theatre – a barn – in Connecticut – they’d cut a couple of characters as they could not fit them on stage. They had one spotlight, but it had all the essence of what it made it work originally. They were so honest and sincere about everything they said. I went out weeping.

“But sometimes, in mounting A Chorus Line, they get too caught up in reproducing the technical aspects. When really it’s all about heart. Its heart is the most important thing.”

Avian goes on to explain that he believes the show remains so popular with audiences because is it about the “everyman”. He says: “At the end of the show, my mother thinks they all got the job, and she is so happy,” he says. “But what you are really seeing is that these dancers have worked so hard to be totally anonymous. That is the double power of the finale.”

The music in the show, written by Marvin Hamlisch, is also powerful, I suggest. Who can forget What I Did For Love when they’ve seen the production? It also helps that this song is the one from the show that tends to get most airplay on the radio.

Avian reveals that Hamlisch wrote What I Did For Love after begging to be allowed to pen one number that could work as a standalone song.

Sadly, Hamlisch died in 2012, and Avian expresses regret the composer didn’t live to see the London revival. “There is only me left from the original team,” he sighs. “It’s pretty scary, and very sad. They were all too young.”

Bennett died in 1987, ending a partnership with Avian – who was his associate – that had seen the pair work on shows such as the 1971 Broadway production of Follies and the 1981 staging of Dreamgirls.

In fact, when Bennett was dying, Avian was asked to come to London to choreograph a production of Follies being produced by Mackintosh.

“I did not want to recreate Follies in the UK,” he reveals. “I had been known as Michael’s associate all those years, I did not know if I could do it. The original was so magnificent, but painful too, as we were not a success and we lost at the awards ceremonies. But Michael said, ‘This is good for you, to do a show you are familiar with, even though it will be different’. He was right, and I struck up a relationship with Cameron, and then one thing led to another. I was scared to death, but I think it was a good thing.”

The relationship he has built with Mackintosh has seen Avian choreograph or take responsibility for the musical staging of West End productions such as Martin Guerre, Miss Saigon and The Witches of Eastwick.

“Cameron had me trapped in his house,” Avian jokes. “But he has been so wonderful to me and has treated me so well.”

The Witches of Eastwick was his last production here, but Avian admits that, even though he was booked to do it, he did not want to.

“But Cameron brought Stephen Mear to work with me on it which was a perfect solution,” he says. “He could do a lot of the leg work, which I find harder the older I get. My body won’t do it anymore. Stephen and I were chemically suited to each other, and that made it work.”

He adds: “I had a good time doing it. We had so much fun.”

So will he come back and do more work in London?

“If we are fortunate to run long enough here that we have a cast change, I will come back,” he says. “It’s a very important market.”

But as for something new, something that isn’t A Chorus Line, we’ll have to wait and see. We can but hope he doesn’t leave it another 12 years.

A Chorus Line opens at the London Palladium on February 19

Opinion

Opinion

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99