Want a career in technical theatre? Here are tips on the route forwards

Lighting designer and programmer Rob Halliday offers advice on what the training options are if you are looking to pursue a career in technical theatre

Over the years I’ve spoken at lots of them, lit shows for many of them, and have a regular annual ‘guest slot’ at one of them, but I didn’t actually go to drama school. My route was instead through the sort of ‘unofficial’ drama school of the day, the lighting team of the National Youth Theatre of Great Britain, then doing a ‘proper’ degree (computer science, since you ask, most of it now horribly outdated) at the behest of my academic parents.

However, I ended up spending most of my time in the theatres on or around campus, then the ‘school of life’ of actually doing shows, particularly two years of going around the world with the English Shakespeare Company.

Every week in a different city, sometimes in a different country, is a fantastic opportunity to learn about so many things, from the feel of different places to the diversity of theatre architecture, to the about five minutes you have to get a (usually tired, having just finished someone else’s get-out) crew on-side to get your show in.

‘Times have certainly changed – the range of skills required in any of the technical fields has increased exponentially’

There is a generation of theatre practitioners who grew up on the job, in many cases in theatres where the previous generation of practitioners were happy to hand their skills down, who’d wonder why you’d ever need to go to drama school to learn what we do.

But that isn’t necessarily true now. Times have certainly changed. The range of skills required in any of the technical fields has increased exponentially: just to take lighting as an example, you used to plug a light into a dimmer and then turn it on; now, you’ll have to rig it, plug it into power and data, address it, chose from one of many modes and then quite possibly get involved in configuring a network infrastructure to make it work. It’s more complicated. And that rep theatre where you used to get the hand-me-down knowledge? It has quite possibly closed. Instead, very often you’ll become freelance, turning up job to job with the expectation that you’ll arrive knowing what you’re doing.

So, you need somewhere to learn. This might, or might not, be a drama school; maybe it’s an apprenticeship with a technical supplier.

If you think that drama school is the right route for you, there are many to choose from, so how do you choose? Go look, is the obvious starting point. Get a feel for the location – do you want to step out into the buzz of the city or the calm of a quieter campus? Talk to people while you’re there, staff and students. What do their answers seem to tell you? What do the pauses between their answers, the subtext in their words, tell you? How stable does it feel? New staff might be good – fresh opinions, points of view, experiences are always welcome. On the other hand, a new head tutor every year for the past three years could suggest some kind of turmoil – but what if the latest one is the one who’ll stick around and be brilliant? Don’t be afraid to do your research on the staff, or to ask them about this.

Continues...

Then the practical stuff: what gear will you have access to? How current is it? What suppliers does the course have good connections with, and how are they used?

Spending some time out in the real world is useful. Spending all your time palmed off on one supplier and perhaps you could just have done an apprenticeship there and cut out the organisation in the middle (and the related cost!).

And, of course, think about it the other way round as well. What will your relationship with the institution be? How will you take advantage of what it has to offer you? I think what drama schools can offer you, should offer you, is a freedom to experiment, a freedom to – in effect – ‘play’, though it can be hard to use that word now, especially given the costs involved. They should offer an ability to try things without the overriding pressure for it to be ‘right’ that will become a driving force post-college, and with time to do so free from the neverending deadline pressure that seems to arrive the moment you step out of college. A good college will offer that (though they sometimes should impose deadlines, so you get used to them!), but it takes a good student to take advantage of it.

The other thing a good drama school should offer is good fellow students, since almost everything we do as technicians needs a team to make it happen: be prepared to support others in their playing, and they’ll support you in return. Quite possibly for far, far longer than just your time together in college; the main thing I still carry from my NYT days is the people.

Other things? Be sure ‘this’ is what you want to do before you commit to these years of expensive training. ‘This’ might be a vague notion: precisely what ‘job’ you want to do will quite probably change as you learn (and probably beyond), but really it means understanding and accepting the peculiar working hours and work-life balance that being a part of this industry brings.

And, most importantly, whatever technical training route you choose, keep in mind that even when you graduate in a few short years’ time, that’s the start of a learning journey, not the end. A drama school can teach you many things, but it cannot teach you about walking into a new theatre in a new town early on a cold winter’s morning and getting everyone on your side. That, and so much more, you do still have to learn; for the best people that learning journey never ends.

Opinion

Recommended for you

Advice

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £5.99

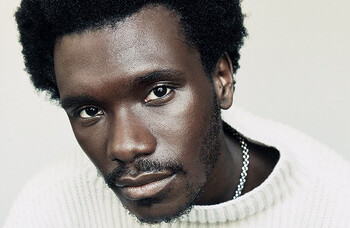

Rob Halliday

Rob Halliday