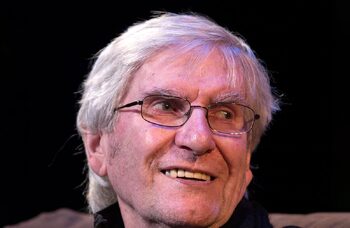

Improv teacher Keith Johnstone: 'Look inward rather than outward for inspiration'

How did you start off teaching improv?

As a play reader and director at London’s Royal Court in the 1960s, we found ourselves with studio space but no money for teachers. As a director, you were expected to teach. So, having no previous training, I had to start inventing things. I told my students: “Let’s learn together.” And we did.

What is the best part of your job?

The best part of teaching improv is when I can take the group through a positive process, and it feels like everything is functioning right.

And your least favourite?

You can’t create the ‘safe space’ necessary for successful improv if you have even one or two mean-spirited people in the group.

Who should students be looking up to?

Once students have mastered the obvious and reached the point where their work is flowing freely, they should look inward rather than outward for inspiration.

What one skill should every successful theatre/dance professional have?

Henry Irving’s answer to a similar question more than 100 years ago is still pretty good: ‘Voice, voice – and be truthful.’’ The struggle to be truthful makes your work worthwhile.

How does it feel to see so many of the improv exercises you originated continue to turn up in comedy shows on TV and stages around the world?

The ideas often don’t go anywhere. Unlike the masters of ceremonies in these types of show, if I am working with a group, I don’t just shout suggestions, I am there with the actors making them work.

Are there different challenges to teaching improv in different countries?

Not really. Humans are naturally defensive, so you get the same techniques no matter what the country. But the English do understand ‘positive misbehaviour’ in a way that is difficult to teach anywhere else.

Keith Johnstone has taught at RADA, the Royal Court and Theatresports Institute and will be in London for a 10-day masterclass starting November 29. He was talking to John Byrne

Opinion

Recommended for you

Advice

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99

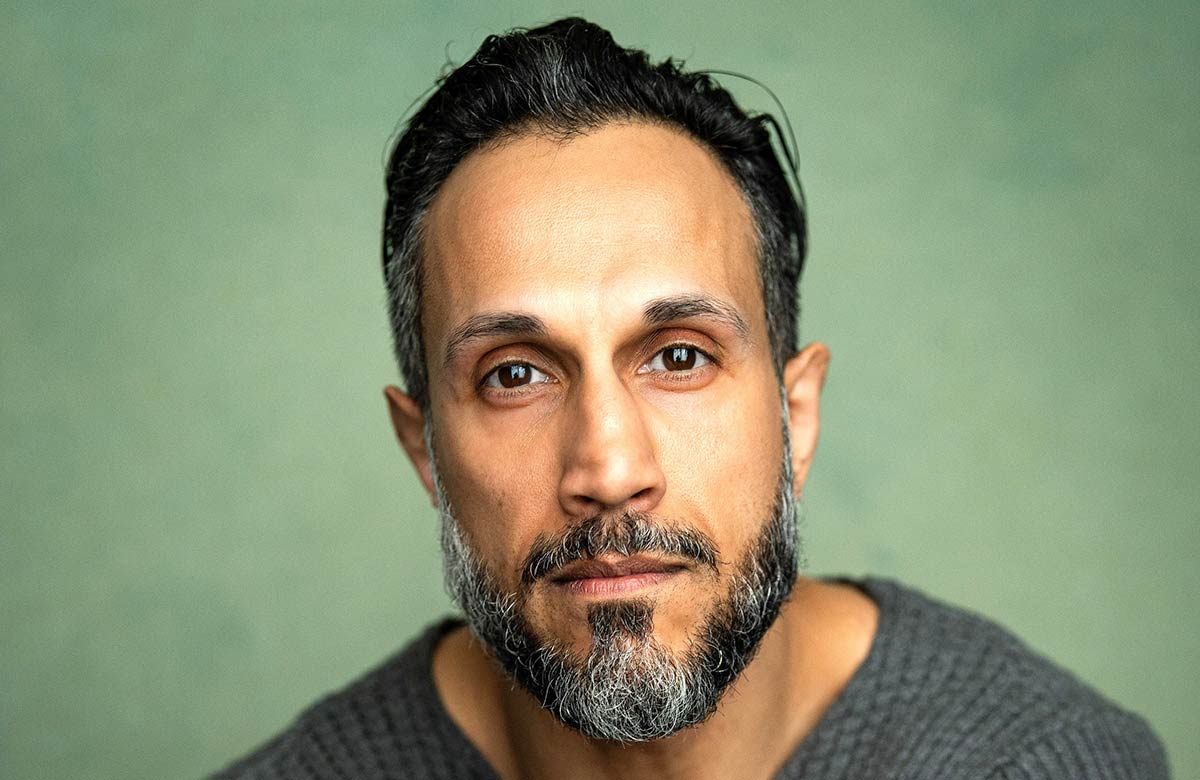

John Byrne

John Byrne